Browse

In the year 1841, a Malay-speaking scribe in Singapore named Abdullah Bin Abdul Kadir wrote about his visit to the Sesostris, a British ship laying in harbor on its way to China. In lively prose, Abdullah recorded the dimensions of its tanks and pipes using Malay measurements, and awed at the hulking men slaving away in the boiler room. He described the disciplined crew dusting, sweeping, oiling and polishing its decks and engines like clockwork, “so that all the iron and brasswork gleamed like a mirror”(註1) It was unlike anything he had seen before. A Malay sailing craft needed about a week to travel between Singapore and Abdullah’s hometown of Melaka, but the Sesostris could do the journey in just thirteen hours.(註2) Naming it Cherita Kapal Asap (The Tale of the Steamship), Abdullah gave us the first Malay description of a steam-powered vessel.

In Abdullah’s time, the Malay world was experiencing tremendous upheaval and great change. The early 19th century saw the decline of the old Malay maritime kingdoms and the expansion of European colonial power. In his memoir, Abdullah recorded the wonders of this brave new world: in Singapore where he spent many years teaching the Malay language to Christian missionaries and European traders, he saw not only steamships, but also the daguerreotype and Western medicine. Constant interaction with foreigners exposed him to developments happening oceans away. He repeatedly talks about the Malays “falling behind” in a world on a relentless march into the future.

Singapore was one of the few places in this region where such change was felt most directly. By 1824 the British had succeeded in securing full control over the island with a treaty that stripped its principal Malay chiefs of all powers. Together with the Dutch, they divided the sprawling Johor-Riau Sultanate – of which Singapore was part – between them. The same line is the basis for the borders between the present-day countries of Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia today

The establishment of a British entrepôt in Singapore, free from the conservative censure of the Malay royal courts, created a new site for bold literary developments. Of course, Malays had always shifted from island to island and port to port for centuries, wherever there was living to be made. Singapore to them was yet another place for opportunities that sprung up in their region, where fixed borders and passports were such foreign concepts.

Cries of Protest

Among the Malays in colonial Singapore were many literate people who produced social critiques and commentaries on their condition. Important themes in the few works that survive from that period include the struggle and exploitation of common labourers in the colonial city. In the same year that Abdullah wrote his account of the Sesostris, another writer – known only by his scribal nom-de-plume ‘Tuan Simi’ – penned two scathing poems that condemned the cruelty of the British East India Company and the colonial authorities. In Syair Potong Gaji (Ballad of the Cut Wages), the poet described how their pay was steadily reduced despite each man being forced to do the work of three. He draws on vivid metaphors to convey the physical agony they faced:

Terendanglah kami tidak berminyak

Dengan air terbakar, dengan angin tertanak

Hati dan jantung sangatlah senak

Pendapatan seperti utan dan semaWe are fried alive without oil

Grilled with the air, boiled with the wind

Liver and heart both filled with pain

We are paid in sticks and stones(註3)

These are not pretty verses; they are dark words reaching through the page like a desperate plea, from a people bereft of hope. Their lot was “Like that of ships wrecked on reefs / Or so many birds without nests”(註4) They had petitioned the Company without success. From almost two centuries past that voice rings clear: “O Singapore, you land of lords / Now renowned in every place […] Let it be known to you this moment / Of the difficulty that we face”(註5)

The opening of Singapore port may have brought prosperity to its merchants and administrators, but countless labourers suffered untold misery. Bitterly the poet remarks how the Company, whom so many had earlier hoped would shelter them “like a great tree offering shade”(註6) to all nations, only brought despair. The poet was keenly aware of the fact that colonial capitalism had upended the old order for good, and life under the kings had passed away. In another poem, Syair Dagang Berjual-beli (Ballad of the Trading Sojourners), the same poet made the grim observation that “Now the Merchant rules the land / A sign that the world has ended.”(註7)

Malay Print Cosmopolitanism

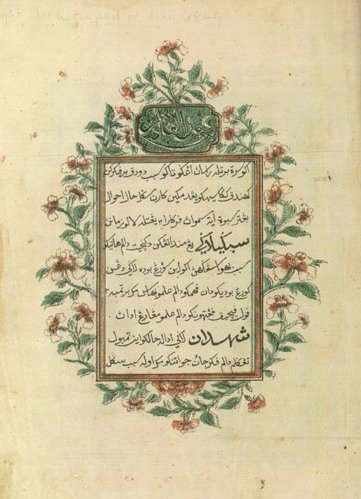

British Singapore was also where Christian missionaries – while waiting for China to open itself up to trade and eventually, conversion – based themselves. With them came the printing press, a technology adopted with great enthusiasm by Malay-speaking locals. Indeed, Abdullah’s memoir was the first Malay book to be printed en masse.(註8) Prior to the print revolution of the 19th century, the only ‘books’ that were being produced were handwritten manuscripts. These were mainly kept in royal palaces, wrapped in silk and read aloud on special occasions.(註9)

Books were not easily produced and relatively scarce, so only a limited number was in circulation. One also needed to have the right social connections to have access to them. The print industry changed all that, when a publishing boom began in the late 19th century. In 1890, a single printer in Singapore in one year, produced the same number of books as the estimated total of Malay manuscripts produced in the past four centuries combined.(註10)

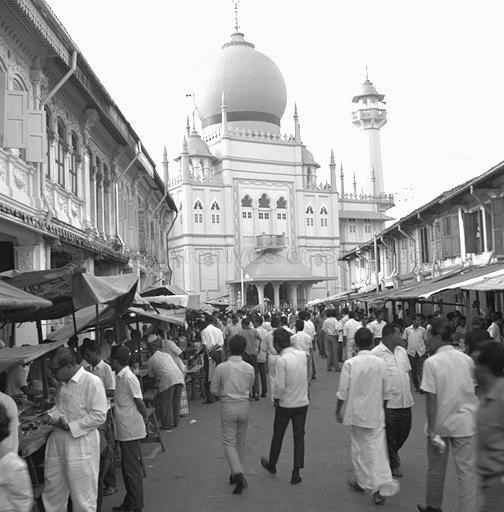

Most of these printing houses were located in the royal precinct of Kampong Gelam, once the seat of the titular Sultan of Singapore. Between the 1880s and 1890s, Javanese traders like Haji Muhammad Said and Haji Muhammad Salleh established printing houses there. However, they primarily produced Qur’ans and religious tracts. Crucially, it must be noted that the pioneers of Malay print culture were not Malays themselves, but people of diverse ethnicities who spoke the Malay language as it was the lingua franca of trade and diplomacy in the region. Some of these were even communities of foreign ancestry, but because they had been in the Malay world for generations, they had adopted its language, customs and even cultural forms like cuisine and dress.

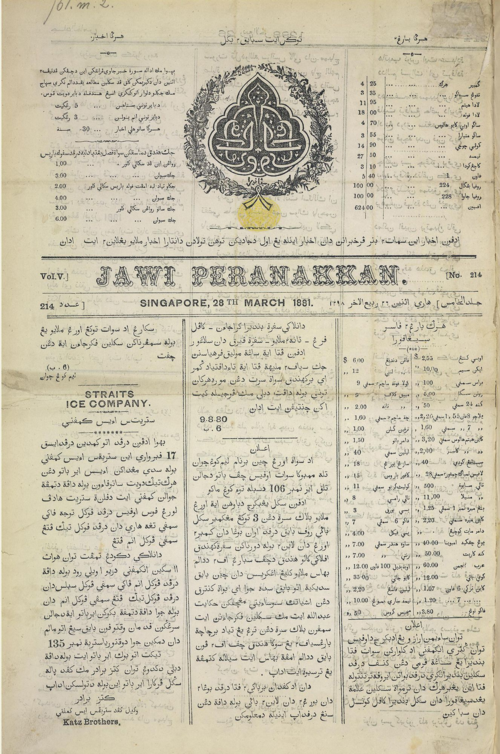

These included the Jawi Peranakan: Indian Muslims with Malay ancestry. Some enterprising members of this community, including Mohammed Said Bin Dada Mohiddin, established Singapore’s first Malay newspaper, Jawi Peranakan in 1876.(註11) The Chinese Peranakan were also actively involved. Also known as the ‘Straits’ Chinese, they were of mixed Chinese and local ancestry. Established as merchants in port-cities like Melaka, Penang, Batavia and Semarang, they too spoke a trade variety of the Malay language.

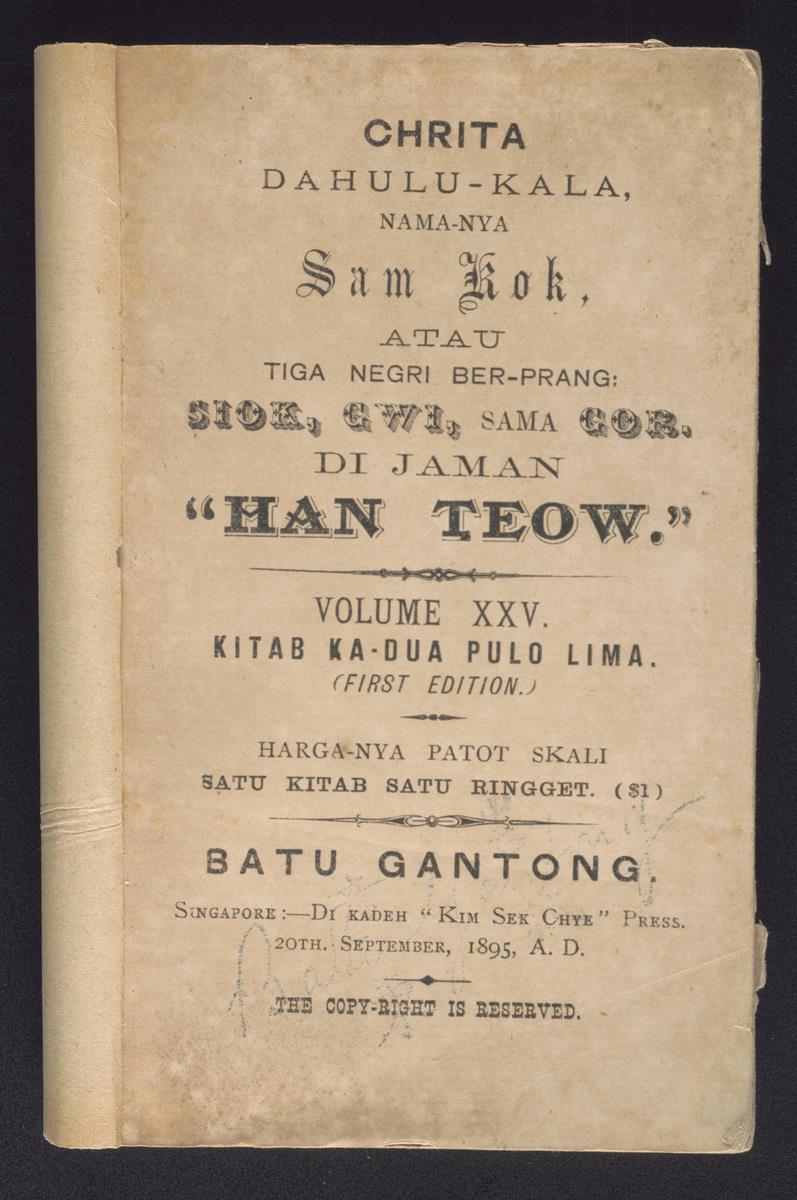

Between 1892 and 1896, the Kim Sek Chye Press of Singapore founded by Chan Yong Chuan produced the first Malay translation of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, entitled Chrita Dahulu Kala, Namanya Sam Kok, Atau, Tiga Negri Ber-Prang: Siok, Gwi, Sama Gor di Jaman ‘Han Teow’.(註12) Serialised in 30 volumes, it was well-received and enjoyed a long print run. Chan’s press also produced Malay translations of two other classical Chinese novels: Shi Nai An’s The Water Margin (Song Kang) as well as Journey to the West (Kou Chey Tian).(註13)

As these examples show, Malay writing and printing were not the reserve of Malays alone. The Malay language and its written tradition were modes of expression employed by a diverse range of different groups, in Singapore and across the Nanyang. For instance, historian Claudine Salmon studied the development of Malay literature produced by Chinese in the Netherlands-Indies, beginning in the late 19th century.(註14)

In fact, the Straits Chinese were pioneers of adopting the Latin alphabet to write Malay, as opposed to Jawi (modified Arabic script) which was the dominant script used at the time. There were three important Chinese Peranakan newspapers in Singapore which used the Malay language: Surat Khabar Peranakan (Peranakan Newspaper) and Bintang Timor (Star of the East) – both began in 1894 – and Kabar Slalu (News Always) which started in 1924.(註15)

Many of the Singapore Malay newspapers of the early 20th century were also established by Malay-speaking Arabs. Warta Malaya, started in 1930 was owned by the wealthy and influential Alsagoff family. One of its editors was the prominent Arab-Malay scholar, Syed Syeikh Al-Hady. The important role the Malay language played as a medium for communication across cultures in the region for centuries was one it continued to enjoy even in the age of print.

In fact, that so many Malay printed works were produced by non-Malays reflects the creation of a regional cosmopolitanism based on Malay as a print language. This print culture facilitated the expansion of public discourse and popular literature, providing a forum for the dissemination of ideas and narratives.

Radical Intelligentsia

Between 1900 and 1920, tens of thousands of Malay peasants were sent to vernacular schools established by the British colonial authorities in Malaya (including Singapore).(註16) The subsequent increase in general literacy amongst the Malay commoners drew them into the new modern consciousness generated by newspapers and books. This generation of folk literati formed the basis of a radical Malay intelligentsia that sought to improve the Malays’ standard of living, demand political and economic justice, and eventually build a nationalist movement to challenge colonial rule.

In 1906, school administrators R.J. Wilkinson and R.O. Winstedt, with the help of a Malay aristocrat named Raja Haji Yahya of Perak, created the ‘Malay Literature Series’.(註17) The old epic sagas and poems were now printed like textbooks and taught to schoolchildren, including famous titles like Hikayat Hang Tuah (The Tale of Hang Tuah), Hikayat Raja-raja Pasai (The Tale of the Kings of Pasai) and Sejarah Melayu (The Malay Annals). These shaped their conception of the Malay past, idealized as a period of valour, heroism and courtly splendour.

One of the products of this curriculum was the novelist Harun Aminurrashid, born in Singapore in 1907. As a teenager, he pursued higher education at the Sultan Idris Training College (SITC). There, he was exposed to ideas about being part of a wider ‘nation’ encompassing the entire Malay Archipelago numbering some 70 million souls united by a common language.(註18)

Harun was a prolific writer. His first major work, Melor Kuala Lumpur (Jasmine of Kuala Lumpur), was published in 1930 and drew on his experiences at the SITC. The story centers a student, Sulaiman and his love affair with Nurisa. In it he explores the same questions that preoccupied many of the Malay literati of the time:

We’re talking about Malay progress, and why the Malays don’t get on in life, until we’ve nearly run out of ideas. But we still haven’t found the secret.(註19)

His other famous works included Cinta Gadis Rimba (Love of a Jungle Maiden), which concerns a free-spirited Dayak girl who rescues a Malay man from captivity and marries him.(註20) Published in 1948, it was made into a radio show and adapted for film by the Cathay Keris studio in Singapore.(註21)

When Harun returned to Singapore, he quickly got involved with the local printing industry which experienced another boom after the Second World War. In 1949, the newspaper Utusan Melayu celebrated its 10th anniversary with a special edition. It was the first newspaper fully owned, financed and staffed by people considered ‘racially pure’ Malays, unlike earlier periodicals like Warta Malaya or Jawi Peranakan. The paper was established by members of the first Malay political party, Kesatuan Melayu Singapura (Singapore Malay Union). These included the prominent merchant Haji Ambo’ Sooloh and Yusof Bin Ishak, an English-educated journalist who later became the first President of Singapore. To finance the paper, Utusan’s founders travelled across villages and towns selling shares to taxi-drivers, farmers and ordinary workers.(註22) Fitting for a newspaper aiming to be the voice of the people, advancing their interests.

The establishment of Utusan was part of a broader left-wing Malay anti-colonial movement now in full swing. At this time, Singapore was governed as a separate colony from the rest of British Malaya. The Malay kingdoms were protectorates of Britain, while other port-cities like Melaka and Penang were, like Singapore, under direct colonial administration. Nevertheless, the boundaries were porous and there was little preventing the free movement of people and ideas throughout Malaya.

Budding journalists and writers from the Malay Peninsula turned Singapore into the main epicenter of progressive ideals and calls for political action. They were closely acquainted with artists, composers and musicians in the city, which was also the Hollywood of the Malay world. Some figures from Malay cinema, including the famous filmmaker P. Ramlee, were influenced by ideas current within these literary circles. One such maxim held sacred amongst the intelligentsia was the notion of art for society (seni untuk masyarakat).

In 1950, the first literary association in postwar Malaya was founded: the League of Writers ’50 (Angkatan Sasterawan ’50, usually shortened as ASAS ’50). It counted several illustrious figures amongst its members, including short-story writer Kamaludin Muhammad (Keris Mas), Mahsuri S.N., song lyricist Jamil Sulong and the venerable poet Usman Awang. One important personality behind ASAS ‘50, A. Samad Ismail, was also a founding member of the People’s Action Party, which has governed Singapore from independence to the present.

Within ASAS ’50 there soon emerged a heated debate that would split the writers into two separate schools. The likes of Usman Awang and Keris Mas clung to the principle that art should serve society. On the other hand, the columnist and lyricist Hamzah Hussin, novelist Rosmera and poet Abdul Ghani Hamid among others, believed in art for art’s sake (seni untuk seni). They were unable to reconcile their differences and the dissenting faction broke away to form the Association for New Malay Letters, or Persatuan Angkatan Persuratan Melayu Baru.(註23)

ASAS ’50 played a crucial role in institutionalizing Malay literature and shaping its development as a modern genre.(註24) Harun Aminurrashid, however, was involved in another literary society known as the Malay Language Board (Lembaga Bahasa Melayu) together with schoolteachers and broadcasters.(註25) Meanwhile the eminent linguist Zainal Abidin Ahmad (alias Za’ba) was professor at the University of Malaya’s Department of Malay Studies, then housed on a campus in Singapore. His students also formed a literary club and published their own literary journal Bahasa.(註26)

This blossoming of literary organisations coincided with a time of robust political activism. Malays were fiercely debating what their national future would look like. Right-wing traditionalists advocated a federation of the Malay sultanates, whereas left-wing socialists believed in the overthrow of the monarchies and the creation of a Malayan republic. Eventually, however, it was the conservative United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) that came to power in Malaya as the country achieved independence in 1957. That year, Harun Aminurrashid wrote what is perhaps his most famous work, Panglima Awang (Commander Awang). It is a historical novel based on the life of Enrique de Malaca, a Malay slave of Ferdinand Magellan who accompanied the Portuguese explorer on his voyages. He dedicated the book “To Welcoming the Independence of the Federation of Malaya”.(註27)

The Humanist Poetry of Usman Awang

The ideology of UMNO was one of Malay racial nationalism, which held that Malaya belonged to the Malays, and that they should be conferred special privileges and protection. Yet one poet, Usman Awang, best represents an alternative current. Like other Malay socialists including Ahmad Boestamam and Said Zahari, Usman Awang believed ultimately in a Malaya built on shared values of social justice, equality and the dignity of the worker and the common citizen (rakyat), regardless of ethnic origin. In his poem Tanah Melayu (Malaya), he calls upon the people’s capacity to come together and make their demands heard:

Dengarlah jeritan keras petani di ladang

Dengarlah teriakan gemuruh buruh di kilang

Sama bersatu sederap barisan bangun berjuangWhen oppression reaches deep into our bones

Hear the harsh cry of the farmer in the fields

Hear the thundering roar of the workers in the factories

United in a single step, our ranks rise together in struggle(註28)

Like Tuan Simi a hundred years before, Usman recognised the same subjection of workers to brutal exploitation. However, he responded by deploying language drawn from socialist notions of class solidarity and collective organization. More importantly, there was little distinguishing the class struggle from the fight for national liberation.

The leftist Malay intelligentsia understood that capitalism was colonial capitalism, as the extraction of resources from their land entailed the suffering of their own people in the interests of British industry and the global bourgeoisie. In Kabar dari Asia (Tidings from Asia), Usman commemorates overcoming capitalist subjugation under European masters in triumphal terms:

Dulu kita dipaksa jadi tukang sapu

Tuan-tuan gemuk bayar gaji sambal goyang kaki

Ada sahabat di belakangnya dililiti cemeti

Jadi lembu pedati kerja tanpa gajiIn the past we were forced to become sweepers

While those fat masters gave our wages while swinging their legs

Meanwhile our friend behind him was coiled by a whip

Made to be a cart ox for work without pay(註29)

As an internationalist, Usman expressed these aspirations for liberty and justice as inherently human ones that transcended cultures. He situated the cause of Malay nationalism within a wider pan-Asian movement. Kabar dari Asia was penned in commemoration of the 1955 Bandung Conference, which Sukarno called “the first meeting of coloured peoples in human history”. Usman’s poem was a clarion call articulating the spirit of Afro-Asian solidarity:

Hidup baru mula di sinar terang sekali;

Dua benua berpadu dalam satu hati

Afro-Asia… untukmu kami berbakti.Life has newly begun in splendor so bright

Two continents united in one heart

Afro-Asia… you alone we serve(註30)

Things were not so rosy in Malayan politics, however. A crucial question in the debates about the new nation was the place of non-Malays like the Indians as well as the Chinese, most of whom were concentrated in the towns and port-cities like Singapore. Malay anxieties about their subordinate economic position vis-à-vis the Chinese had been expressed since the 1930s. Even scholars like Za’ba and the journalist Abdul Rahim Kajai had openly racist disdain for these ‘immigrants’. Usman Awang, however, embraced the Chinese in Malaya as fellow compatriots. “Young Chinese men and maidens, here is our earth and sky”, he proclaims, seeing them as part of a common Malayan homeland. Pemuda dan Gadis Tionghoa (Young Chinese Men and Maidens) was composed in 1961 in celebration of the Lunar New Year, and dedicated to three of his friends: Linda Chen, Goh Choo Keng and Lim Huat Boon. All three were prominent scholars of Malay language and literature.

Lihatlah makam nenek moyang sebagai sejarah terpahat

darahnya dalam darahmu segar di kulit kuning langsat

esok, ketika tahun baru, akan kukirimkan sebuah angpau

dalamnya sebuah cinta dari jantung tanah dan pulau!Look on your ancestors’ tombs as history inscribed

Their blood is in yours, fresh under your skin fair as the langsat fruit

Tomorrow, for the new year, I will bring you an angpao

In it, love from the beating heart of this land and all its islands!(註31)

Interestingly, Usman chose to use “kuning langsat” (langsat yellow) to describe the skin tone of Chinese people; langsat (Lansium parasiticum) is native to the Malay Peninsula, and using it as a colour description appropriately reflects his ideal that the Chinese belonged to the soil as did the Malays.

Usman went on to produce several more poems illustrating the life of the Chinese in Malaya. These included poems about Chinese fishermen, an ice-lolly vendor, a grocer, factory-workers and painters of the Nanyang school. Many Chinese in Singapore active in the anti-colonial movement did see themselves as Malayan and insisted on fighting for its liberation, despite being given the option to return to China. Hundreds even enrolled in classes to learn Malay, the National Language.

Unfortunately, however, there was little Usman’s tributes to his fellow Malayans could do to prevent the influence of racial politics. In 1963, Singapore, along with Sabah and Sarawak merged with Malaya to form Malaysia. All along, however, Malaya’s Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman was against the idea of unification with Singapore. Among other reasons, there was fear that Singapore’s large Chinese population would threaten UMNO’s vision for a Malay-dominant society.(註32) On the other hand, politicians in the Malaysian government saw Lee Kuan Yew as a Chinese chauvinist.(註33) Political riots erupted in Singapore in 1964 between Malays and Chinese as a result of the tensely racialized climate of the time.

In 1965, Singapore was expelled from Malaysia. An exodus of Malay writers, artists and scholars ensued. In one fell swoop, the entire flourishing ecosystem of Malay pop culture and literature in Singapore disintegrated. Usman himself, like many others, moved to Kuala Lumpur. Singapore became a sovereign republic, but to the Malays who stayed, it felt like they had been made cultural orphans, cut off from a wider world from which their best talents came. This marked a new phase in the development of Malay literature in the city.

“I’ve Lost my Soul”: Alienation in the New Nation

Separation from Malaysia induced a marked shift in the mood and tone of Malay literature in Singapore. Overall, the works from the late 1960s up until the 1990s can be described as expressing a kind of bleak pessimism. As Singapore embarked on a program of rapid modernization, Malays felt increasingly alienated from a society that swept away older patterns of life which once defined their community. The poet Suratman Markasan drew attention to how the violent transformation of Singapore’s landscape to pursue its image of a gleaming modern city left him unmoored:

Laut tempatku menangkap ikan

bukit tempatku mencari rambutan

sudah menghutan dilanda batu-bata

[…]

Aku kehilangan lautku

Aku kehilangan bukitku

Aku kehilangan dirikuThe sea where I went fishing

The hill where I searched for rambutans

Have been forested by slabs of stones

[…]

I’ve lost my sea

I’ve lost my hill

I’ve lost my soul(註34)

He criticized the valourisation of questionable historical figures, including Stamford Raffles, the East India Company employee who established a British settlement in Singapore.

Di sekolah aku diajar ilmu sejarah

Raffles menemui Singapura

raja mendapat kekayaan menjadi besar empayarnya

sultan mendapat wang menjadi gemuk tubuhnya

pendatang bertambah hidupku tak berubahIn school, I was taught history

that Raffles founded Singapore

who gained glory, till his empire expanded

the sultan received money, till his body grew fat

immigrants swarmed in numbers, yet my life remains the same(註35)

Perhaps his most fiery critique of the State’s adoption of colonial symbols in its national history is Balada Seorang Lelaki Di Depan Patung Raffles (Ballad of a Man in Front of Raffles Statue). The unnamed protagonist recounts the atrocities of British imperialism against Malays, with the silent statue of Raffles on the banks of the Singapore River as his target:

Raffles tersenyum kaku

Lelaki hilang kepala menggerutu

“telah kukatakan seribu kali

kau menipu datukku hidup mati

kau merampas hartanya pupus rakus

kau bagikan kepada kawan lawan

kau dengar Raffles? Kau dengar?

Seharusnya kau kubawa ke muka pengadilan

Di PBB kota New York

Tapi sayang hakim tak punya gigi”Raffles kept his frozen smile

The man who lost his mind started ranting

“I’ve said a thousand times

you deceived my grandfathers in life and death

you seized their possessions rapaciously

you divided the spoils amongst your friends and foes

do you hear me Raffles? Do you hear?

I ought to drag you to stand trial

At the United Nations in New York City

Too bad those judges are toothless too”(註36)

Literary sociologist Azhar Ibrahim argued that poets like Suratman Markasan were responding to the new regime’s emphasis on efficiency, nation-building and productivity, while failing to preserve the people’s rights and welfare. In his analysis, Azhar notes how Suratman is aware of the depressing state of affairs in his community, but like many others, he is not able to illustrate fully the structural problems that caused the displacement of his community: the lack of resources and social capital, apart from the policy of exclusion from mainstream development that prevented the Malays from being an integral part of the development process especially from the 1970s when Singapore entered a robust phase of industrialization and urbanization.(註37)

The same sentiment is perceptible in the works of Mohamed Latiff Mohamed, who condemned the decadence and excess of modern Singapore in his novel Kota Airmata (City of Tears), even as so many continued to languish in poverty. In his poem Potret Singapura (Portrait of Singapore), Latiff returned to the theme of geographic erasure, as historical Malay districts got demolished as sparkling new residential areas were built:

[…] merapati dirimu

terkenanglah

rindu pada temasik

melaka dan selat tebrau

sambil berjalan di orchard road

atau masuk ke rumah pangsaI recall Geylang Serai

And the village of Wak Tanjong

As they became Ang Mo Kio

Pek Ghee and YishunAs I come close to you

I reminisce

Longing for Temasik

Melaka and the Straits of Tebrau

While walking along Orchard Road

Or entering a block of high-rise flats(註38)

Turning to the old royal palace of Kampong Gelam, long bereft of kingship, he laments how it is but “a sign of sorrow / a marker of despair / after a hundred full moons were drowned / in pursuit of development.”(註39)

A sense of disempowerment, loss, and alienation would endure as predominant themes in Malay literary works in Singapore after Separation. Mohamed Latiff Mohamed, Mahsuri S.N. and Suratman Markasan however, held the fort as key members of ASAS ’50. Of course, it may be tempting to dismiss these works as dull and depressing, but they played an important role giving voice to the frustrations and angst of Singapore’s Malay community.

New Directions: 1990s-present

In 1992, a young playwright named Noor Effendy Ibrahim wrote Anak Melayu (Malay Child). Set in contemporary Singapore, it centers a group of six Malay friends, teenagers struggling with sexuality, drugs, traditional values and current trends.(註40) It was widely criticized in the Malay press for being lewd, irreverent and using vulgar language. The 1990s saw the emergence of a new generation of Malay writers, but unlike novels, short stories or poetry, it appeared as though Malay literature found new life in plays. It was the theatre that functioned as a new site for literary experimentation, where not only themes expressed in dialogue and plot, but also performative gestures challenged, subverted and complicated orthodox ideas about Malay propriety and identity. Anak Melayu created such an uproar that reports were filed by members of the public to the police. The Criminal Investigation Department even asked for the graphic language to be removed from the performances, but the theater group, Teater Kami eventually retained it.(註41)

Then there was Aidli ‘Alin’ Mosbit, whose play Dan Tiga Dara Terbang ke Bulan (And Three Virgins Fly to the Moon) was staged in 1995. It too scandalized the Malay community for its candid conversations on gender discrimination and sexuality.(註42)Kosovo at the age of 19, Alin soon helmed other pieces of her own with Teater Kami. In 1998 she wrote another controversial play, Ikan Cantik (Beautiful Fish), which shocked the Malay community with its cast of six actresses who shaved their heads and used vulgarities on stage.(註43)

This was a new cohort of Malay writers that dared to push the boundaries beyond what was conventionally acceptable even within their own communities. Indeed, their works dealt with radically different issues compared to those which preoccupied the Malay writers of past generations. There was no stirring national movement to mobilise for; these were contemporary subjects that interrogated the dogmatic beliefs of community elders, and asked what it meant to be young and Malay – and indeed, ‘Singaporean’.

The same year Ikan Cantik was written, another fresh-faced writer of 21 years – Alfian Sa’at – published his first collection of poetry. Entitled One Fierce Hour, it was noted as a hallmark in the development of Singapore poetry. Critically acclaimed, Lee Tzu Pheng called Alfian “a natural poet” and “something of an enfant terrible” for his sharp – even brutal – reflection on Singaporean identity.(註44) Some of the pieces in the collection have become canon in Singapore literature, including Sang Nila by Moonlight and the classic Singapore You Are Not My Country:

O Singapore your fair shores your garlands your GNP.

You are not a country you are a construction from spare parts.

You are not a campaign you are last year’s posters.

You are not a culture you are poems on the MRT.

You are not a song you are part-swearword part-lullaby.

You are not Paradise you are an island with pythons.(註45)

His next poetry collection, A History of Amnesia (2001) dealt with darker themes including interrogations and political detentions without trial. To date, Alfian’s corpus of plays includes 26 works in English, 17 in Malay and one in Mandarin. A small number are altogether polyglot, including Hotel (2015) which told 200 years of Singapore history through a single hotel room, in nine languages. Tiger of Malaya (2018) took as its subject a Japanese propaganda film from World War II, and its multilingual cast slid seamlessly between Malay, Japanese, English and Mandarin.

Some of Alfian’s pieces still engage with themes that concerned earlier cohorts of Malay writers. Anak Bulan di Kampung Wa’ Hassan (1998), Causeway (1998), Nadirah (2009) and Geng Rebut Cabinet (2015) deal with Malay traumas regarding resettlement, displacement, Separation from Malaysia, religious conservatism and ethnic discrimination. Notably, however, most of his works are in English, which should compel us to expand our definition of ‘Malay literature’. As we have seen earlier, Malays were not the only ones producing literature in the Malay language. And clearly, Malay writers in Singapore today have moved beyond just writing in the Malay language, and are perfectly at home using English as a medium for expression. This does not make their works any less ‘Malay’. Alfian’s 2012 short story collection Malay Sketches succeeded in capturing both the absurdity as well as the heart-rending complexity of the Singaporean Malay experience, despite being entirely in English.

It is helpful that Malay works are being translated; Alfian Sa’at himself translated some pieces into English, including Menara (The Tower), a novel by Isa Kamari. A decorated writer, Isa Kamari’s is short story Pertemuan (Meeting) won an award from the Singapore Malay Language Council in 1997. While other works have also garnered him various accolades, including the prestigious Cultural Medallion in 2007. In 2016, he wrote an English novella entitled Tweet.

Other Malay writers working in English include Nuraliah Norasid, whose critically-acclaimed work novel The Gatekeeper(2017) is set in the fictional realm of Manticura. A year before publication, it already won the Epigram Books Fiction Prize: at $25,000 it is the biggest literary cash prize in Singapore, awarded to unpublished novels.(註46) In 2018 The Gatekeeper won Best Fiction Title at the Singapore Book Awards. Another novelist is Imran Hashim, whose sojourn in France inspired his comedic work Annabelle Thong (2016). And then there is the satirist Suffian Hakim, who with his “grand talent for writing silly”,(註47) reimagined Harry Potter as a Malay Singaporean in Harris Bin Potter and the Stoned Philosopher (2015).

What seems to be occurring is the emergence of Malay writers who are no longer simply confined to the concerns of their own community. On the other hand, it grapples with the place of Malay life in multicultural Singapore, inhabiting different styles, tropes and even languages. This multiplicity defies the Malays’ framing as a monolithic and minoritised ‘Other’ by the State. While one key feature is their ability to deftly maneuver between English and Malay, this is not to say that Malay writers are only now more ‘legible’ because they are effectively bilingual. On the other hand, these new, more experimental literary trends demonstrate that their Malay experiences need not be provincialized within the realm of the Malay language alone nor the same set of thematic concerns. Their experiences are diverse and can encompass multiple linguistic, thematic and formal registers. This literature inhabits an inter-disciplinary practice: for example, sharp wordplay blends with choreographed movement and visual aesthetics in the works of Irfan Kasban.

The problem of language – its constraints and subversive potential closely intertwined – remains a preoccupation. Hamid Roslan’s debut poetry collection parsetreeforestfire (2019) gives voice to the Malay Singaporean who has always existed across multiple speech communities. The verses – a delightfully confounding brew of English and Singlish – are defiantly trans-lingual:

Use your brain. If got formula

we sure export lah bodoh. Kan dah kenabodoh. Don’t ask me for footnote. When

you read English you look up. They alwaystell you speak up boy speak up

now I speak up.

Also dismantling language barriers since 2016 is the sole playwright collective in Singapore that focuses on developing scripts in both English and Malay: Main Tulis (literally ‘Play Write’) Group. Its founder Nabilah Said emphasizes the members’ internal diversity: they are all Malay playwrights, but come from different age groups, backgrounds, and levels of experience.(註48) And while Malay writers today are no longer mainly organized into many literary associations as in the past, Main Tulis Group – in its own way – embodies that legacy. Adib Kosnan, Nabilah Said, Zulfadli Rashid and Ahmad Musta’ain Khamis, as well as its other members can be said to form their own ‘angkatan’ (generation or movement).

The Group’s name can’t be more apt. I claim no critical expertise in contemporary Malay theatre, but quite like Hamid Roslan’s poems, what stands out to me from the handful of plays I’ve seen is precisely this juxtaposition between high-seriousness – possibly inherited from the earlier tradition of Malay intellectual activism – and attentiveness to play. Gone is the brooding didacticism of the social-realist sandiwara; malaises are experienced through banal tragedies; they are laughed at; and in being toyed with, momentarily defeated.

This is perhaps one of the many things garnering literature by Malays its increasingly mainstream appeal. More non-Malays in Singapore are attending performances staged by theatre companies such as Teater Ekamatra and Panggung Arts, and reading either the works of Malay novelists, and poets. Malay literature of the present moment insists on the legitimacy of its voice in shaping discourse on matters that concern all Singaporeans. Alin Mosbit noted this succinctly: “Nowadays, when I talk about Malay issues, I don’t feel like I’m talking about them as Malay issues. I really feel that it’s our issues – each and every one of us. If you call yourself a Singaporean, whatever that’s affecting me now will somehow affect you.”(註49)

Conclusion

Witnessing the growth of the bustling new port-town in Singapore in the 1840s, Abdullah Bin Abdul Kadir wrote, “I am astonished to see how markedly our world is changing. A new world is being created, the old world destroyed.”(註50)

We can sum up the story of Malay literature in Singapore as a quest for finding one’s place in a perpetual state of newness and flux. For more than a century, Singapore was at the forefront of the development of modern Malay literature. It was the site of first contact for many new technologies that changed the way Malays engaged with text and narrative.

Previously, Malay literature was sustained by a courtly scribal culture and a folk oral tradition. But the publishing houses, vernacular schools and the press in cities like Singapore gave birth to a lively print culture, a literate reading public and a robust critical discourse to debate matters of common concern. Singapore stopped being the premier centre of Malay literary activity when it was expelled from the Malaysian Federation. Severed from a broader Malay community, its literature proceeded to give voice to a marginalized minority in a country that was modernizing beyond recognition.

In recent decades, new generations of writers articulated the fractious relationship between their Malay and Singaporean identities, in a way that felt at home in both. Their open engagement with taboo subjects often earned them the title: kurang ajar (ill-taught; deficient in manners). While their unorthodox methods may be read as a revolt against traditional cultural expectations, it can be seen as a revival of the spirit of resistance embraced by the radical intelligentsia before them, with a lineage perhaps going all the way back to the cries of Tuan Simi. Usman Awang himself once declared,

No people can ever be great

If they do not possess this spirit of kurang ajar.

Faris Joraimi is an undergraduate interested in pre-modern Malay history, and writes about contemporary cultural and social phenomena in Singapore.