Browse

I saw her and a sad dried stalk of grass in the previous lives

I saw her sitting crying when rain poured down in the afternoon wood

The wood turned yellow, she was not yet home

The wood blew the winter wind, she stood alone

I saw her and a lone sun in the previous lives

I saw her sitting singing when cloud came to the wood

In the changing autumn wood, flied sadly clouds

In the freezing winter wood, gurgled the rain

I still hope, I still keep waiting for her in every solitary day

I still hope she is back there, so the life can celebrate then

Spring comes, darling, please return! The old wood has closed, darling, please get out!

The old wood has closed, the old wood has closed, darling, please get out!

“The Old Wood Has Closed” (註1)

“The Old Wood Has Closed” is a poem and song composed in 1972 by Trịnh Công Sơn (註2) portraying an image of a derelict woman who gets stuck in a dreary forest as a metaphor for bardo, a Buddhist notion describing a middle state between death and rebirth, while her lover is waiting for her reincarnation in many different of his lives. In the poem, the lover is conscious and able to open his third eye – the eye of wisdom to view his beloved helpless in such transitional situation which can become dangerous place since she can not raise her transcendental insight to liberate herself. Being at a visionary’s position, he is calling her in his hopelessness.

Step backwards from the Buddhist meanings, the dreary forest could be seen as a patriarchal society where the woman get caught by its complex patterns and never find out a way to escape. Looking at the woman’s position in our nowadays society, like the poet, I also want to urge the woman to “get out” and set herself free from that liminal state. But how? Almost a half century later, artist Nguyễn Trinh Thi created chances for the woman to reincarnate into different lives. Reusing found footages from a range of Vietnamese classic fictional films featuring the same central actress, Như Quỳnh – a representative of Vietnamese beauty, produced mostly by the state-owned Vietnam Feature Film Studio, Trinh Thi revives the woman from a unawaked human to a visionary in Eleven Men and Song to the Front.(註3) In these works, the woman is capable to reveal not only her roles in society but also the other real, in which we are able to reflect ourselves.

From Eleven Men to Song to the Front

In 28 minutes black and white and color movie Eleven Men, the woman presents herself as a double person: one telling her life by looking at the others and the other living her life. “I have eleven men” – the narrative begins with the woman’s voiceover and presents her life story in two halves: the first half in black and white indicates her character once she was young; and the second half in color depicts her images when she is getting older. Above all, the woman appears as a second person, who could get out of those contexts and gaze at herself from a certain distance of time to tell her story.

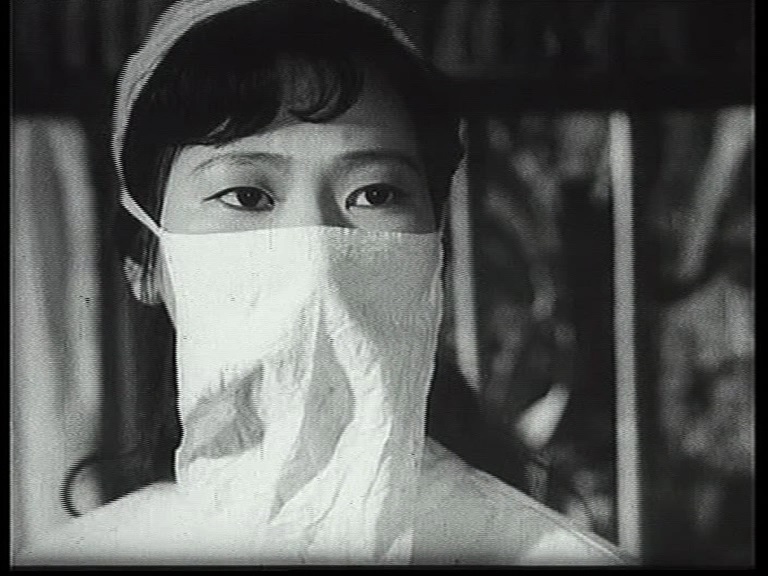

In her early age in black and white, the woman firstly lives with her seven men one after the other. In these scenarios, she appears as a young woman fulfilled with different emotions either happy or unhappy, sure or confused, but overall she seems to be innocent and passive in her relationship (fig. 1). Her intimacy is more hidden in the public eyes. But from the eighth man on, her appearance changes into color as if another one of her. Her behaviors change completely into audacity. She becomes more active, melancholy and utterly knows exactly what she wants and exposes her intimacy more often as if her natural character (fig. 2).

This change happens not only in the woman’s character but also in Vietnamese cinematic history before and after the economic reform (Đổi Mới policy) (註4) in 1986. In the composition of scenes from a serials of Vietnamese classic movies produced over three decades from 1966 to 2000, Đổi Mới becomes a milestone marking a shift of chronicling the woman in Vietnamese media. Before this milestone, the woman is presented in an innocent, faithful and passive shape as a representative of the nation serving the socialistic propaganda and war mechanism. Afterwards, she appears as an experienced and melancholic woman in exotic settings serving the commercial world. This politics of presentation is ironically revealed in Eleven Men as an art installation of images combined with a text adapted from Eleven Sons, a short story by Franz Kafka in 1919. In the new presentation, the woman is no more presented but rather presents herself.

Song to the Front: From Being Presented to Being Present

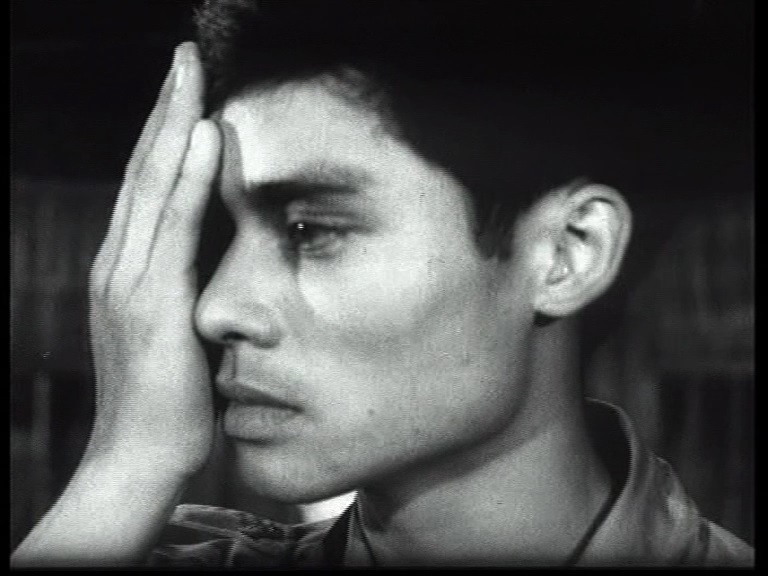

Not only in a position of self presenting, the same Trinh Thi’s woman is also able to reincarnate herself actively into the other’s life. As a nurse in five-minute-film Song to the Front, the woman observes the man in his changing process as changes of an age, in which she lives as a silent witness (fig. 3). The moving images in Song to the Front are the recut of the propaganda movie with the same title originally made in 1973 praising glory of the soldier in the battlefield. In this recut, Trinh Thi shifted the narrative’s focus from the man to the woman and combined with the music set to Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. The Stravinsky’s opera is about a sacred ritual where a sacrificed young girl dances herself to death to propitiate the god of Spring. This dramatic music in the background has deepened those changes into questions on meanings of ideologies, believes and genders’ roles in the society: Patriotism in the original film seems to become a danger which could pull a human being into its violent whirlpool in Trinh Thi’s movie; a soldier is no more a hero but a victim of his time and becomes an object under the woman’s gaze (fig. 4); and believes on what is right or wrong become all of a sudden so ambivalent and controversial. Without any conversation, the gaze took place silently via the third eye beyond the surroundings and out of the frame. In the both films, through the enlightening inner view, we can see an endless love based on wisdom, for one after the other, time to time in a mature process, in such the woman’s personality was built.

The Two Sides of the Coin: The Women within Her Social Context

From this wisdom, the woman is visionary keen on a patriarchal world surrounded by viciousness and vulgarism as once exhibited in Hero Mother in June 2016 in Berlin.(註5) The international contemporary art exhibition presented 44 artworks by 31 women artists from 20 communist or former communist countries including Nguyễn Trinh Thi exposing the redefinition of notions on heroic women in the post-communism.(註6) While most of others’ artworks expressed the woman as victims of or rebels and activists against heroism and war mechanism, the woman in Trinh Thi’s images could step back from that stage to suggest viewers to take a deeper look into our mankind.

However, in another orbit, there is another woman still got stuck in heroic mothers’ roles presented in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Like the other dark side of the moon compared with the one in Berlin, the woman in the permanent exhibition of Vietnamese Women’s Museum in Hanoi is constructed from socialist values fulfilled with social functions: getting marriage, giving birth, nursing family and being “heroic mothers”. Serving as a political instrument, their lost children and husbands should be seen as sacrifices and honors for “the battle for the reunification of the country”.7 None of them is viewed in any other dimension, in which they could be out of their context in order to look back and review their lives.

Linking the two kinds of women’s presentation in the two cities, I can only see the two woman’s versions in a unity like two sides of a coin, either they are a pro or contra version of heroism, but none of them enables to get out of that social context to redefine their roles in society. In the same situation with the woman in Trịnh Công Sơn’s poem, they are staying still, wandering in liminal states, in socialist and post-socialist exhibitions or traumatic dreams of one who lived that life. They can never reincarnate.

Amongst those images, Trinh Thi’s woman could auspiciously open her wisdom eye to get out of her contexts. In such, she chooses to position herself based on her own wisdom and compassion as a way of liberating herself and achieving her inner happiness. Becoming a witness of time spectrums, she could comprehend the world’s imperfectiveness and love its human beings patiently from time to time. However, through her enlightening, we can see, on the one hand, her contentment, but on the other hand, a darkness of a hopeless world, in which there is no progress, no better change even through already many of her reincarnated lives. Looking through the woman’s vision, we can never know whether it is right or not to keep ourselves in a viewing position to gain tranquility for our own soul or to become fighters to help this vulgar world become a better place.

NOTE: Thank you to Ying Ying Lai for her invitation to contribute this essay. Thank you also to Nguyễn Trinh Thi, Phan Thuỳ Phương and Nguyễn Quốc Thành for reading earlier drafts; to Andrea Lauser for encouraging me; and especially to artist Nguyễn Trinh Thi for generously providing her images for reproduction here.

Original doctoral research at Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology and the Ethnographic Collection, Georg-August-University of Goettingen, was made possible by support from the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom 2016-2019, Independent Art in Vietnam since the 1990s. Political power for a civil society?