Browse

On 28 March 1958, the biggest traffic jam in Singapore’s history took place along the eleven-and-a-half-mile stretch of Bukit Timah Road and Jurong Road, west of the city. The occasion was the opening of the new Nanyang University Nat-natal founded by the Chinese community; the tens of thousands of guests and well-wishers, some invited but most turning up on their own, started the journey early in the afternoon, intending to reach the campus and catch the official ceremony scheduled to take place at four that afternoon. It was a scene of utter chaos. As the tropical sun began to set, Bukit Timah Road and Dunearn Road were blocked by heavy north- bound traffic, with the confusion worsened by the south-bound traffic from Johor and Bukit Timah Road. The police could not untangle the jam, and 400 extra troops from the paramilitary police reserve unit were called in to help. Despite these reinforcements, the traffic along Jurong Road still came to a standstill. Thousands of people left their cars by the roadside and walked the six miles to the university grounds. The Governor, Sir William Goode, was to open the celebrations at four o’clock; he reached the university two hours later arid unveiled the commemorative plaque at seven in the evening.

Thousands eventually arrived in this manner. From the reception marquee they spilled onto the lawn and garden below, and the festivities took much of the sting out of the long, sweaty journey. As they looked up into the night sky, three huge gas-filled balloons lifted off, carrying goodwill messages on long, red, flowing paper strips, and then the fireworks started, filling the sky with myriad flashes of gold and red before trailing off into the far horizon. For the first time in Southeast Asia, a self-funded university had been founded to cater for the thousands of graduates of Chinese secondary schools. As an educational institution, it also carried the long historical ambition of preserving Chinese culture and tradition in the South Seas (Nanyang), and producing university graduates who were culturally astute, modern in outlook and employable.

If Nanyang University’s inauguration was marked by the problem of traffic control, its ending, too, was foreshadowed on a similar note. But there was no question this time of massive chaos along the ten-mile route from the city to the campus. Early one June morning in 1964, a half- mile-long convoy of 60 police vehicles and Black Maria vans set off for the university at two hours past midnight. The convoy was escorted by Mobile Traffic Police to make sure the road was clear of any other traffic except police vehicles. By three o’clock the convoy had reached the university grounds; a roadblock was set up half a mile away, at the Jurong Police Station. With the exit secured, the pre-dawn crackdown on communist subversives at Nanyang University began.

The 1,300 students were asleep when the police arrived at Nanyang Avenue. For the operation, the Federal authorities’ called in more than 1,000 police personnel from the Special Branch, the Federal Reserve Unit, the Criminal Investigation Department, the Divisional Police and the Mobile Traffic Squad in order to cordon off the campus. Two hours after the police had entered the campus, the first student detainees were brought out in a van. At the Jurong Police Station roadblock, a Special Branch officer checked all vehicles against a wanted list of names and photographs; students were identified and detained, and 11 others were arrested outside the campus. A total of 51 students were arrested, including four girls. The eight-hour police operation was the biggest since the arrest of more than 100 left-wing unionists and politicians in Operation Cold Store a year earlier. By the time the public woke up, the police convoy had begun to leave the campus, and by ten in the morning, the operation had been completed.

The cast the hectic, unruly movement along the road to the campus, and the final exercise of control, as a metaphor for the rise and fall of Nantah is in no way an overstatement. Nantah’s story is one of raw social energies and movements — of new ideas; of social visions always at risk of going awry in the volatile social and political conditions of the time; and of the needs and agendas of the political forces on both sides of the Causeway. It was a time of national struggle and the end of colonialism. Everyone who wanted a stake in the new nation-state was caught up in the changes and what these could bring. Indeed, history made radicals of everyone who aspired to power in the post-colonial political order; the ‘communist-inspired’ Nantah students were not the only ones deserving of the label.

But the story of Nantah also tells of movement of another kind: that of the immigrant imaginary. (pp170-172)

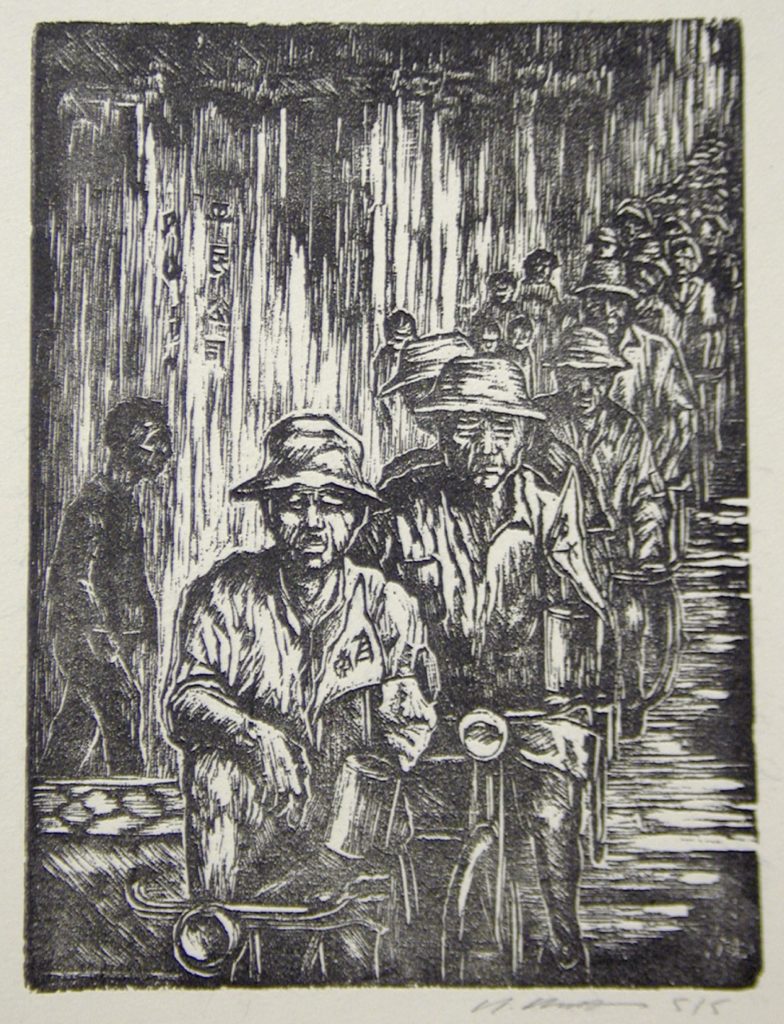

There was a great deal of collective spirit and earnestness in the activity. Accustomed to viewing Chinese community undertakings through the prism of personal power and the status of the merchant elite, one tends to forget the potency of cultural identity that bridged and unified the social divide. Nantah was very much that, a symbol of the collective yearning to put down the roots of Chinese culture in Southeast Asia. People I interviewed spoke fondly of the fund-raising drive; they had a term for it, yi mai (selling for a cause). The Nanyang Hakka Association held a concert in Kuala Lumpur and tickets, together with bottles of cognac, wall clocks and an assortment of trinkets were auctioned off at a grand dinner the night before. Bottles of Remy Martin went for $1,000 each as rich businessmen dug into their wallets as ‘face’ demanded of them. The concert and dinner collected more than $15,000. Other concerts and auction dinners were organised by Chinese she tuan(voluntary associations) all over Malaya and Singapore. The slogan was, ‘Those who have give money, those who have not give labour! True to this spirit of grassroots engagement, hawkers, rickshaw drivers and labourers donated their earnings for the day. Hair saloons offered yi flan and yi dian (CHECK TEXT) (cut and perm for a cause). On 4 May, Chinese dance hall hostesses in Singapore gave their day to yi une (dancing for Nantah). It was a hugely successful event, collecting some $20,000. One man went to Nan Tien Dance Hall in Chinatown, combining personal pleasure with doing his bit for a good cause, but it was not enough to pacify his wife’s rage when he got home, he told me. In Ipoh market in Malaya, one fishmonger nicknamed ‘Da Shu Tau’ (Big Tree Trunk) put on a raggedy shirt and turned beggar for a day. Wandering from stall to stall, he collected some $1,200; when his shirt and begging bowl were later auctioned, they were bought for $65 by the Ipoh Vegetable Sellers’ Association.” (p174)

The communist-based organisations had a special place in post-war Malaya and Singapore. Enjoying considerable popular appeal, the communists formed the only effective guerrilla force against the Japanese during the dark years of 1942-45. The retreating British had sought collaboration with the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), the militaty wing of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), in organising stay-behind parties for gathering intelligence for the Southeast Asia Command in Ceylon. For its part, the MCP had hoped to strike a bargain with the British and perhaps carve out a legitimate political role in pose-war Malaya. In any case, in the relatively liberal climate after the war, organisations with varying degrees of communist influence grew; so, too, did labour unions, student societies and trade associations, whose diverse ideological aims could be loosely described as anti-colonial, democratic-socialist and multi-ethnic. It is problematic to label these organisations as ‘communist’; so is tracing their direct or tacit links with the MCP and its off-shoot, the Ex-Comrades Association. This is a controversial issue that is not easily resolved, clouded as it is by state propa-ganda and erroneous thinking. In this regard, Harper is most astute when he describes these associations as underlined by ‘a common ground between the “Eight Points” of the Malayan Communist Party, the republicanism of the Malay left, and the global solidarities of revived trade unionism’. In short, the post-war socialist struggle blossomed in the hothouse conditions of the anti-colonial struggle, nationalism and rising political consciousness generally.

To explain the modern consciousness and desire for progressive education among the Malayan Chinese, we need to go back further. After its founding in 1911, the Chinese Republic faced the turbulent difficulties of a new regime; the political conflict and modern cultural aspirations were inevitably exported to the Chinese in Singapore. Before the revolution, the Qing government had at first left the overseas Chinese community very much to themselves, but at the turn of the century, with the late Qing reform and the stirring of national revolution under Sun Yat Sen, the Chinese government and the revolutionaries both began to compete for political support among the overseas Chinese. The picture of modern Chinese nationalism presents a dramatic contrast to the images more famously depicted of traditional China -the culture-bound, compliant masses, the political influence of the literati, the merchant elite who purchased titles from the government as marks of prestige and honour. China’s modern nationalism rose from the ashes of the Opium War (1839-42). Another critical event was the disastrous six months’ war with Japan in 1894-95, which saw the annexa-tion of Taiwan and Southern Manchuria by Japan. But the most crucial was undoubtedly the May Fourth Movement of 1919.(pp176-177)

Tracing the origins of this activism, as I have done, to modern China and post-war politics, with its imperative of economic security for the poor, is not to explain away its passion and violence and arguably, its links with the Malayan Communist Party. Half a century on, one should perhaps resist nostalgia for the ‘failed revolution’. Yet as we speak of the naivete and youthful enthusiasm of students in Nantah and the Chinese high schools, we ought not to forget that they were not the only ones seduced by the elegiac vision of a democratic-socialist society.

The PAP leaders then taking Singapore to national independence, too, were inspired by the utopian vision. The young extremists in Nantah may have been too easily swayed by communism, but their energy and drive were still something desirable-if only these qualities could be harnessed and guided down a less revolutionary path. The fortunes of Nantah were famously tied in with the rise of the PAP government, but the story is not just about official suppression and how it brought about the university’s ultimate demise.

The history of Singapore from 1954 to 1961, a period covering the founding of the PAP to the departure of its left-wing faction, is generally described by the PAP as being ‘astride [the back] of the tiger’. A popular cartoon book depicts Lee with his legs straddling the ferocious beast, right fist in the air clasping the PAP party emblem, ready to land a blow to its head. His clothes in tatters, face grim with determination, it is the visage of a man in the midst of battle as he strikes terror in the enemies visibly cowering under the tiger’s belly. Melodramatic at best, the cartoon celebrates the heroism and danger of the PAP enterprise; it was no ‘paper tiger’ on whose back Lee and his colleagues rode to power. When he returned to Singapore from his studies in England, the young Lee found himself in a heady atmosphere of anti-colonial nationalism and socialist radicalism… Lee’s politics were of a different ideological hue…Nonetheless, Lee was deeply impressed with the energy and commitment of the students and labour organisers he came into contact with. Here is his passionate assessment:

…one day in 1954 we came into contact with the Chinese educated world. The Chinese middle school students were in revolt against national service and they were beaten down. Riots rook place, charges were preferred in court … [It was] a world teeming with vitality, dynamism and revolution …

The commitment and dedication of the left was all the more impressive when contrasted with the English-educated who, like Lee himself, benefited the most from colonial patronage. For Lee, the greatest sins of the English-educated elite were their self-interest and their failure to cast their lot behind the anti-colonial movement.(pp180-181)

To the Nantah graduates I talked to, …. The sense of loss is not only over the demise of the university, but also the end of the cultural ambition of business tycoons and hawkers and dance hostesses alike: the ambition of cultural citizenship, of community identity, of historical depth and transnational inspirations, including a vision for a socialist future. (p. 186)