Browse

This is not the first time Chew Win Chen (Okui Lala) delves into language as a subject of discussion for her art work. Her previous work titled “My Language Proficiency” (2017) explored individuality within a multilingual society of Malaysia: Am I still the same person with each different language I use? A question that seems to be probing mainly into its linguistic significance, is at the same time a reflection on individual life experiences, our ethnic identities and the dialectical struggles amidst the shaping of various cultural policies in Malaysia.

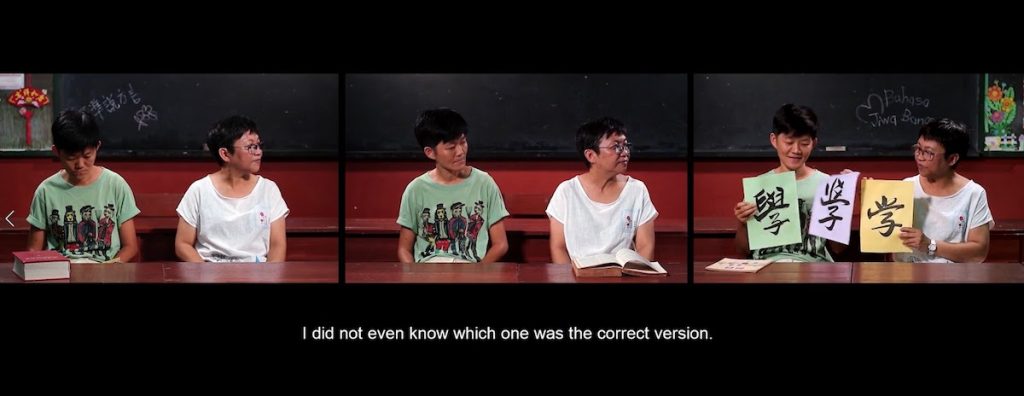

Subsequently, picking up where it was left off, Chew Win Chen took her last work up a notch with her latest video installation at the Singapore Biennale (2019). Besides playing the role of a key speaker herself, five other interviewees, all graduated from National-type Chinese schools(註1) at different periods of time were invited to join the dialogue. A scene is reproduced, drawing inspiration from a painting titled “National Language Class” (1959) by a social realist painter Chua Mia Tee (蔡名智). And by interlacing conversations with interpretations across a three-channel video installation, individual experiences and viewpoints were exchanged, unveiling layers of fragmented and bizarre history of education since the founding of Malaysia as a nation.

Mastery of Language in Plain Sight

The interview opens with the sharing of academic experiences between the participants, outlining some of the policy changes and its transitions across different eras. It covers significant milestones such as school restructuring in the early 1960s where Malay language was emphasised, the shift from traditional Chinese characters in the 1970s to simplified characters in the 1980s, the implementation of 3M basic education (with emphasis on writing, reading and arithmetics) after the 80s and the stigmatisation of dialect-use at around the same time, the requirement to attend remove class(註2) in secondary schools that was revised from compulsory to conditional attendance and finally ended up being abolished. Not forgetting, the policy of teaching Science and Mathematics in English that was established in 2003, abolished in 2012 and revisited recently for reconsideration.(註3)

The volatile approach towards education could potentially lead to more social polarisation. Win Chen’s work is represented by a mere one-sample group among the whole. Besides Malay language, all of the participants could converse fluently in Mandarin. However, Mandarin is not recognised as a National Language but rather a language of the minorities. It is often regarded as the culprit which causes disruption to racial harmony. National Language (Bahasa Malaysia, Malay) may represent a common tongue among all of the participants, but when compared to the other languages, it is perhaps the least fluent language to be used when it comes to expressing deeper emotions. The fact that the National Language everyone can identify with is the official version that was taught in schools, the conversation inadvertently sounds as monotonous as a news broadcast.

The most intriguing part for me is at the use of a third language such as Penang Hokkien or Cantonese which everyone could use with relative ease. However, the degree of proficiency is rather inconsistent, reflecting on the influence and adulteration brought about by previous stigmatisation of dialect [as a form of language]. Despite the compromised proficiency in their third language, the interchangeability between these dialects with other languages felt natural. This is perhaps the most comfortable and least restrained form of communication. It was clearly displayed when three of the Hokkien speakers addressed each other with nicknames that invariably begin with an ‘Ah’. These languages seem to bridge gently the gap between the speakers and their relationships with others.

Therefore, it can be a somewhat delicate task to try to deduce the degree of language proficiency from the interview. With flawed National Language proficiency, will the interviewees be able to communicate their sincerity to other ethnic groups effectively while seeking empathy for their situation and delivering the idea of ‘multicultural harmony’ all at the same time? We could definitely question further; Can language ability be used to measure the level of sincerity in an ethnically diverse society? At what level of language proficiency is one regarded as sufficiently qualified to discuss the matters pertaining to the ‘Respect of diversity’?

What Kind of Diversity are We to Accept?

With more than 60 years since the founding of the nation, the dialogue in which Win Chen converses methodically with her interviewees in a classroom setting is clearly intended for one target audience. Everyone in the same classroom has undoubtedly experienced the same disparity. Take for instance, the case of multilingualism which signifies a national pride that everyone could identify with as a Malaysian; though It is a language skill that is often seen as a unique advantage when one is abroad, it has not been given much importance in this country. There is absolutely no effort devoted to the cultivation of multilingual proficiency. Yet deep within, the ultimate outcry reveals otherwise – Is it so hard to respect each other’s differences?

In this multi-ethnic society, are we to conform to one dominant culture or encourage the growth and development of all different cultures? Or should we perhaps promote the melting pot concept where all different cultures could merge into one? What is the objective of the cultural policy? Which are the hidden agendas and which are the legitimate ones to be implemented?

Today, we still resolve to each making our own statements in Malaysia.

With an unclear notion of “national consensus” accompanied by a highly politicised environment, those who wish to stand out from the rest would need to figure out the vulnerable threshold between ethnic differences and tread cautiously. Otherwise, once the threshold is violated, we risk another undiscriminating major crackdown – similar incidents have been documented in the history of Malaysia(註4). It is also one of the reasons numerous suspicions were raised when the decision to include the teaching of Jawi calligraphy in vernacular schools was announced in the news last year(註5). Even after the realisation of a “New Malaysia”(註6), the attitude of the new Government remains ambiguous. One will never know for sure whose nerve would get wrecked or when.

Hence, through the “National Language Class”, Win Chen has laid out here an “imagined Malaysia”. One that includes aspirations to promote mother tongue and dialects of various ethnic groups and one that calls to retain some of the syllabus in the national curriculum so that future generations have the opportunity to learn different languages and wisdom of life and so forth. These are ideas worth exploring and considering.

Conscious Efforts to be invested in Waiting & Listening

Another interesting point that captured my attention about Win Chen’s work is in the way it is presented to the viewers. The work is exhibited at Singapore Biennale where English Language is the official medium. On top of that, the work is in fact exploring language proficiency as the key subject matter. English language itself, however, plays a secondary role as a subtitle. In other words, only Penangites who shared a similar background as Win Chen would be able to appreciate the work from beginning to the end. This piece of work deliberately calls for more patience to be invested by other language users.

There are nevertheless Penangites of various ethnic groups who chose to abandon their mother tongue or gave up on their dialects. They turn instead to English language which is often perceived to be better equipped with the ability to transcend different ethnic groups. Undeniably, English speakers are more in line with current policy requirements and enjoy better access into social resources than most Chinese-speaking Penangites. However, they will not be able to experience first-hand all those moments of delight and despair in this video installation. Rather, they have to wait patiently for the delayed appearance of the English subtitle which only comes after the interviewees are done with the interpretations in all three different languages they are more fluent in.

If one can detect a divisive inclination among different language speakers in Malaysia from Win Chen’s work, it is not unfathomable. Under the current language and education policies, Malaysians, especially those of Chinese ethnicity, are left divided invariably. Yet all we can do is to be patient and to continue to cultivate more patience. In the meantime, we ought to relentlessly ask, Can we converge all the efforts invested in the needs for mutual translation in the near future, allowing room for the growth of a society with respect for diversity?

For answers to the many more questions that might be asked, we may perhaps look forward to the next effort from Win Chen to take her work another notch higher.