Browse

Whereas many of us who have worked from Taiwan are familiar with or have worked with Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong before, we may know less about its sister institution AAA in India. Based in New Delhi since 2013 and with the aim to reach out to South Asian art archives, AAA in India has undertaken many ambitious projects. We are delighted to invite senior researcher Sneha Ragavan for an interview about the long-running Bibliography of Modern and Contemporary Art Writing of South Asia.

Lou Mo: Hello, Sneha! Thanks for taking the time to talk to us today about the Bibliography! As its name states, Asia Art Archive is an archive. With that in mind, can you tell us about the origin of the Bibliography and how it serves AAA’s mission?

Sneha Ragavan: Thank you for this opportunity to speak with you about AAA’s Bibliography project, which we began in end-2011. There were several reasons for why the researchers at AAA in India proposed to undertake the Bibliography project and I’ll signpost two of the most significant ones here – first, to decenter an Anglo-centric art history that is dominant in South Asia; and second, to bring to light through such an initial exercise of mapping, the rich but invisible multi-lingual histories of art writing from within the region.

The ‘Bibliography of Modern and Contemporary Art Writing of South Asia’ has been a novel project at AAA because the core of our work, as you note, is in making accessible the archives of artists, art historians, critics, and curators, whereas the Bibliography (much like a timeline) is a research tool. However, AAA has always encouraged innovative research projects, particularly those that aim to map less known histories, and that’s how we got the Bibliography project started.

LM: In developing this project, you had to make many choices about what to include and where to find them. Can you elaborate a bit more about this process? How do you adapt along the way?

SR: In a sense, the Bibliography was like any other research project that we all undertake – several aspects of it were planned and parameters were put in place; and as we encountered new situations or materials, we made choices on the spot. For instance, it was a decision we took at the outset to focus the Bibliography on India (it was only in its second phase that we expanded the scope to South Asia). This choice was both pragmatic and contextual. We happen to be based here, and the context for undertaking the Bibliography stemmed from how we were seeing the discourse of art history in India.

When we began working on the project, we also had to restrict ourselves to specific languages we were planning to cover due to limited budgets and time. So we chose 13 languages and this was a difficult task because India has 22 major languages (and hundreds of others!). Part of the rationale for selecting languages came from those we knew that had an abundance of art writing such as Bengali and Marathi; those we knew very little about – such as Odia or Punjabi; and suggestions we received from scholars and art historians. Once we had narrowed down the languages, our process for this involved finding project researchers who would do the work of building this bibliography by visiting public libraries and personal archives. And in a sense, each language/ linguistic region’s bibliography developed in part based on the researcher’s interests, their ability to easily locate and access publications, their innovativeness in tagging, and so on. All of these were choices–so in as much as we planned in advance, several aspects of the outcome were specific to each context, and at times arbitrary.

LM: What are some of the most serendipitous discoveries?

SR: The most glaring discovery was the sheer volume of names of artists, art writers, or art critics that we came across in the bibliography. Despite having a somewhat adequate understanding of art history in the region, how is it that there were hundreds of names of individuals within the field that we hadn’t even heard of? And many of these individuals – be they artists or critics – had prolific careers, with numerous articles or essays by they or referring to them. All these were of course, written in regional languages. It became immediately apparent to us, that that the art history we had studied in school or even the art field that we know of through Anglophone writing is really very narrow in scope, limited to the art of a few cities, and rarely referring to the vast, rich ‘vernacular’ or ‘regional’ art milieus.

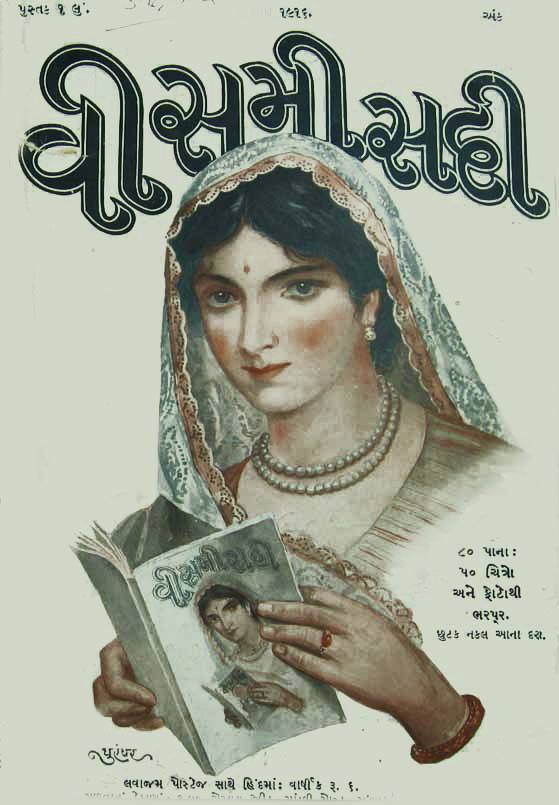

Similarly, another discovery was the role of periodicals as a crucial space for both, the circulation of images of artworks, as well as for the production of discourses and debates on art. These were not ‘art magazines’ (which are a relatively recent phenomenon) but we found numerous articles and essays on art featured within spaces of cultural or literary magazines, alongside texts on literature, drama, film, etc. This provided us with further insights into understanding the interdisciplinary framing of art – very different from how specialised it has become today.

LM: What is the status of the Bibliography project now? How is it accessible?

SR: After the first phase of compiling writing from India was completed in 2014, in 2015 we commenced the second phase of the project to look at art writing in South Asia with a focus on three languages – Tamil, Bengali, and Urdu from Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Pakistan respectively – as these languages are spoken across national borders. Once phase two was completed, we launched the Bibliography project in 2015-16 in the form of a searchable, browsable website accessible to the public at: http://aaabibliography.org.

We felt it was important to take advantage of the fact that the bibliography was compiled as a digital database to present it in this form, replete with advanced search and filters, as well as data visualisations to grant people entry points into this database. This site is the main point of access for the Bibliography project. Although there were several years of lull in terms of compiling more entries for the bibliography, we have recently as part of ‘Mobile Library: Nepal’, a project that AAA is undertaking in collaboration with the Siddhartha Arts Foundation in Kathmandu, have been compiling a bibliography of art writing from Nepal, which is very exciting!

LM: What are some of the challenges you have encountered along the way? Perhaps in terms of inclusiveness or format?

SR: One persistent challenge was figuring out how to engage with writing on craft, folk art, or ‘tribal’/indigenous art practices. For nearly a century, modern artists have blatantly appropriated the techniques, motifs, materials, and visual languages of these so-called ‘lower’ arts into their own practices. So, as a bibliography focused on writing on ‘modern and contemporary art’, how were we going to deal with the copious amounts of texts we found on crafts, folk arts, or indigenous arts without once again engaging in such appropriation? These were after all, entire fields and milieus in their own right. After much deliberation and discussion with researchers on the ground, we decided that only where modern artists had themselves written on these art forms, or when these art forms were discussed within the framework of modernism or modern art, would we include texts on craft, folk art, or indigenous art.

Another challenge has been for us to keep the project ongoing so that even less visible texts, figures, and histories may emerge. We’ve barely scratched the surface so far, and we need support to keep this going.

LM: Did your understanding of modern and contemporary art in South Asia as well as art writing transform during this process? In what way(s)?

SR: Oh definitely it underwent a change! Within South Asia, art history books and essays are predominantly written in English and refer/cite mostly English sources. On top of this, we commonly hear the refrain that not much of significance is being published in the ‘regional’ languages or ‘vernaculars’ – that it is bad writing. We knew this simply could not be true, and wanted to go out there and as researchers learn for ourselves what such an exercise in listing would do to our understanding of art history.

And the bibliography really transformed this for us. Let me give you an example: we had compared our knowledge of art writing from a particular region before and after the bibliography and we were shocked! We may have known some 7~10 artist-writers in Maharashtra, writing in Marathi, prior to commencing the bibliography. We revised this list after we completed the Marathi bibliography, and all of a sudden we realised there were over a 100 artist writers! In short, no longer can we speak of art history in terms of the 20-odd well-known artists and movements, or the 20-odd key texts that have helped build this canon.

LM: South Asia is a geographical territory. Do you think there are limitations of using boundaries such as these? And how does it relate to other areas?

SR: For a project like this, which is a deep dive, a granular approach to the field, it is necessary to work with some limitations. In fact, I feel we are yet to do justice to South Asia as a region in all its porosity. But even though we’ve used South Asia as one framework for the project, it doesn’t limit what one finds within the scope of the bibliography — we’ve found texts detailing experiences of artists/ critics travelling to various parts of the world — be it to work and live, to exhibit, or simply to travel. We’ve also seen the importance of writing about art from around the world in the numerous essays on, say, Chinese murals, or artists like Van Gogh or Frida Kahlo. The way that certain art forms and artist figures became so important for artists in the region to learn from, be inspired by, emulate, or depart from. In that sense, the texts within the bibliography themselves draw connections to a world much beyond South Asia.

LM: A project of the Bibliography’s scope would not leave its host unaltered. How has it influenced AAA in India’s other projects and concerns, such as pedagogy and publications?

SR: The Bibliography project was really the ground on which AAA identified Art Writing as one of its key research priorities. That it is crucial for an art archive to be attentive to, and map the various forms that writings take, the formats they present themselves to us in, and of course, their content. At AAA in India, the project helped us realise the need to bring back into circulation already published texts, and so, we have, for the past several years, been working towards bringing out a set of three publications with writing from various languages found in the bibliography and beyond, translated into English. In 2018, at AAA, Hong Kong, we organised a symposium It Begins with a Story: Artists, Writers, and Periodicals in Asia, which brought together several scholars to explore the diverse ways in which the periodical as a form helped shape artistic discourse across Asia. At AAA in India, the team here has also been working towards a proposal to digitise modernist little magazines (avant-garde magazines) from the 1950s to the 1980s in the South Asia region.

Sneha Ragavan is Senior Researcher and Projects Lead at Asia Art Archive in India, and is based in New Delhi, India. Since joining AAA in 2012, she has, together with colleagues, worked on a range of initiatives including, creating digital bibliographies, digitising artist archives, and organising workshops and symposia on art history from the region. She holds a PhD in Cultural Studies from EFL University, Hyderabad (2016) for her work on twentieth century architectural discourse in India, and an MA in Art History and Aesthetics (2008) from the Faculty of Fine Arts, M.S. University of Baroda.