Browse

Outside the darkened hall, two young women are taking graduation photos on instant cameras, while scattered cosplayers are striking poses on the concrete steps. It’s a cloudy but warm afternoon in mid-November Taichung, and I am the only visitor roaming inside the DigiArk, a long and angular space built one level underground, in the interior court of the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts. I approach the door leading to the first artwork, and a caring exhibition staff member instructs me to put my shoes under one of the jagged wooden benches lining the dim-lit room, to drop my bag somewhere, and to remove keys and sharp items from my pockets. “Are you still interested to experience this work even without the sound? It broke, it’s not working,” she inquires apologetically. I already removed my shoes and keys, so I might as well step into the coffin-like box at the center of NAXS Corp.’s “XR-XATA-01” and sit down on the black inflatable mattress placed inside it. Cold water slushes under my weight. “Be also careful of the lasers, don’t look into the red dots when you stand up.” I am crowned with tightly-strapped VR goggles and silent headphones, and instructed to lie down on my back under the geometric intricacy of laser beams. “Look at the red light, it should start soon. I will tell you when it’s over.”

After a few seconds, the glowing red square hovering over me starts pulsating and recedes in the background as I start falling backwards, effortlessly passing through pixel-thin planes and 3D surfaces. Reddish flat walls and irregular solid volumes recede beyond shifting textures lit by white and electric blue flares, a smudged storm that gives the space expanding in front of my programmed fall the ominousness of a cold hell. It is also a silent hell, and the lack of the audio component of the work makes it difficult to evaluate the experience. The aesthetics embraced by NAXS Corp. are a clear example of postdigital goth: unfinished 3D environments meshed into baroque assemblages, stock textures and a limited range of saturated chromatic gradients shifting across surfaces, and lighting cutting abruptly across fixed vanishing points, all on a pitch-black background. The idea of having visitors experience the work on VR goggles while lying down inside a constrained space is an interesting way of maintaining both immersivity and directionality: I am technically floating through a three-dimensional space, but I can only turn my head a few degrees around the central axis of scripted movement. And yet, after a few minutes of lying down on NAXS Corp.’s “digital raft”, I feel uncomfortable and purposeless: the water inside the inflatable mattress isn’t enough to support my weight, and its chilling embrace approximates the feeling of being locked inside a malfunctioning sensory deprivation tank.

The DigiArk is a peculiar space: light leaks in from the edges of its ample slanted windows, meticulously obscured for the occasion, and the wood paneling on the walls clashes with the exhibition’s starkly digital aesthetics. The six works are generously spaced, making use of corners and alcoves to separate their audiovisual streams as much as possible, and yet the installation soundtracks bleed over one another in cyclical swells. Despite its minimalist aesthetic, Ho Him Shun’s “codenamehk: shitennou” is the most prominent audio presence on display, its estranging melodic kaleidoscope resonating throughout the entire hall. Dedicated to the Four Heavenly Kings of Cantopop, Ho’s work pairs manually altered MIDI renditions of cantopop classics from the early 1990s with repeated lines from each song’s lyrics, flickering with different interference patterns on four vertical screens. The result is somewhere in between the circular deconstruction of vaporwave and the cyclical randomness of Raster-Noton visuals: more than chromesthesia, “codenamehk: shitennou” rapidly triggers an overload of audiovisual dissonance, with the monotonous melodic lines of synthetic pipe organ dissolving into each other, and the pixelated Chinese characters repeated into meaninglessness. When asked about the background of this work, Him Shun emphasizes the nostalgic overtone of the work and his pursuit of an “estranged familiarity” with the Hong Kong cityscape which might be lost to younger visitors not familiar with Cantopop classics from two decades before.

Aluan Wang’s “Paths to the Past” occupies a similar experiential space, with an extra-wide video loop playing over two horizontal screens hanging side-by-side on the wall. The work begins with an aerial view of a Taiwanese city augmented by abstract shapes and markers; a 3D plot of an urban intersection builds itself from the ground up, the empty husks of building models falling into place and shifting around as the visualization rotates. Wang’s exploration of the geospatial structure of his hometown is pinned down by floating coordinates and toponyms, but increasingly disruptive distortions and interferences undermine any connection to place: the colors go off, the video feed fragments in bands of varying width, aberrations blur the edges of the swirling urban elements, and the 3D models switch to wireframe skeletons. The maximalist whirlwind of digital aesthetics of the video is paired with a much less defined audio cobbling together synthesized bleeps and hisses, occasional instrumental samples and bursts of processed field recordings into a mushy soundscape that appears to be mostly disjointed from what is happening on the screens. As the work approaches its ending, the background fades to saturated color hues, and is diffracted by layers of video glitches that turn a recognizable assortment of geographic visuals into colored bands and cubist trails; before looping back to the starting point, the end result looks like a mashup of Minecraft and Google Earth displayed through a malfunctioning HDMI cable.

The three semi-enclosed spaces at the far end of the hall host projection-based works, promising a third variety of synesthetic immersion beyond screens and VR visors. The smallest room is occupied by “Digital Cortex”, a peculiar audio-visual installation by Taiwanese media artist Vibert Thio. Two speakers hanging near the ceiling output rhythmic sequences of ticks and crackles, while an overhead projector fills the back wall with a centered white square in which alphanumeric characters and smaller squares blink and move in sync with the beats. Right below the projector, and physically constraining the audience’s view, is a plinth with a small light box installed on the top, and a Sony DCV-TRV30 camcorder placed on it. The camera is switched on and pointed at the back wall, so that its small rotating display reproduces the projection as a nostalgic low-resolution miniature: is the camera watching the video along with visitors, or is the projection supposed to represent rogue algorithms generating the abstract shapes as the device attempts to replay old cassettes? Thio’s work description, by mentioning rusted ROMs and video encoding errors, seems to hint at this interpretation. Over its few minutes of length, “Digital Cortex” pairs a drab sonic palette of glitch staples (hissing beeps, bit-crushed bleeps, hypercompressed kicks) with a quick run through a handful of geometric visualizations: small squares become a circular point cloud, a planet with floating markers, a blob moving on a grid of letters, and finally a stack of floating white squares in a reddish cubic space. The austere palette has personality and the inclusion of a handheld camera is intriguing, but the video doesn’t embrace it convincingly, and veers instead dangerously close to a tech demo for a VJ plugin.

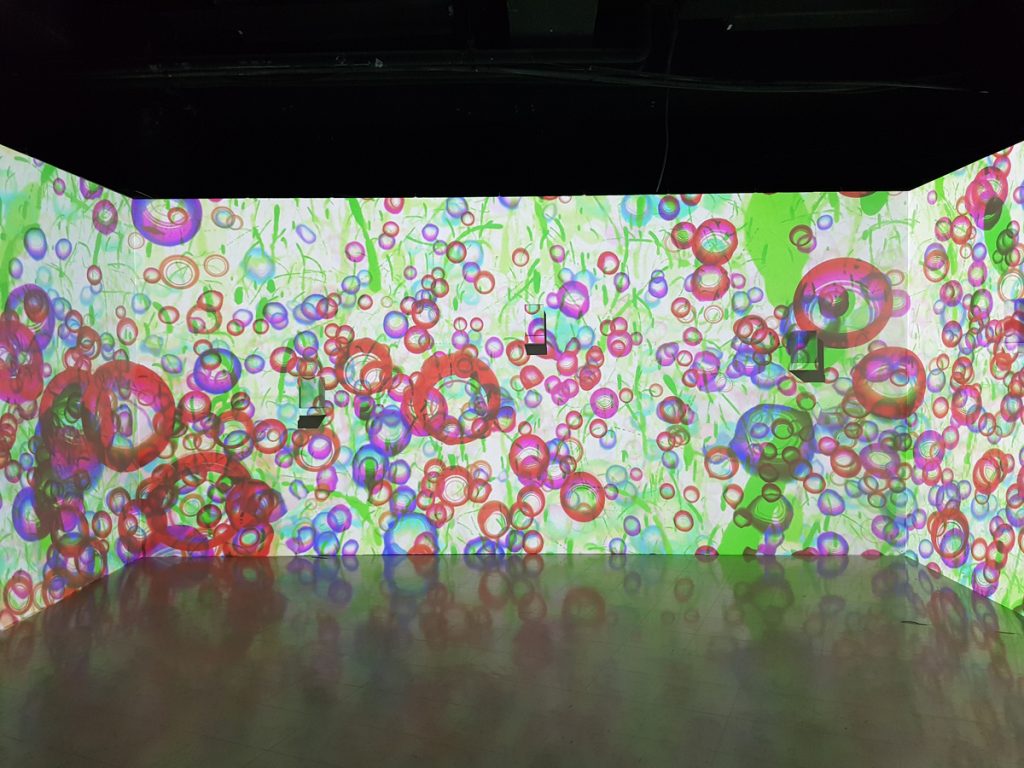

“Dividing a Thing into Hollow and Substance Equally #1″, a collaboration of Satoru Higa and Ray Kunimoto playing in one of the two larger volumes, is the first work I encounter that effortlessly fits the expectations embodied by the exhibition title. The three-channel projection, filling a triptych of white walls, follows a narrative approach to chromatic synaesthesia that is as simple as it is affecting. While sitting on the bench in front of the empty space between the walls, one is drenched by refracted white light, as blurry lines of ink dissolving in water cross-cut the surfaces according to a grid inspired by the traditional Japanese aesthetics of flower arrangement. Horizontal strokes outline mountain peaks, while dots of ink falling from below resemble raindrops splashing in puddles; meanwhile, breezy ambient tones start swelling from seven speakers installed at irregular heights and covered in white mesh. The raindrops become green sprouts, growing rapidly in bigger and broader brush strokes. As Kunimoto’s synthesized strings peak in volume, their sustained notes cross-modulating into gentle flutters, Higa’s projections switch gears, filling the white-washed surfaces with colored circles expanding and contracting. My gaze fixates on a distant point beyond the projection, taking in the chromatic shifts between primary colors that fill my field of vision: I can almost feel the temperature of the air around me change slightly with each blooming of color.

Luckily, the work displayed in the adjacent space plays in alternating slots, avoiding sonic interferences between the two exhibition centerpieces. Kezzardrix and Yaporigami’s “Tilted”, while more imposing and confrontational than the other works on display, is in line with their aesthetic vocabulary. Yaporigami’s sound track is a slick drum’n’bass banger sprinkled with some glitchy samples and veined by airy pads shifting between minor and major chords; Kezzardrix’s visuals, structured over three walls, progress from black and white shapes to greyscale renders. In a curious reversal, here black surfaces are segmented into shifting cubes by a thin white grid, and the syncopated beats drive the morphing geometries into increasingly complex arrangements. When the surface of the back wall breaks into a cubic space delimited by a perspectival grid, an endless line of human figures appears to be walking from one side of the room to the other: some look like stock 3D models, others are deformed by the ripples of frequency peaks traversing their skins. Layers of flat geometric patterns and blurry filters overlap with the three-dimensional renders, revealing and masking scenes within scenes in rapidly flickering bursts of rhythm. I can’t speak about the work’s chromesthetic potential, but its hectic tribute to retro cyberspace imaginaries would definitely warrant an epilepsy warning.

Yeh Ting-hao’s curatorial rationale for bringing these works together is clearly stated in the exhibition blurb: showcasing recent audiovisual artworks from East Asian locales in an attempt to establish the currency of this art form in Taiwan. It is an admirable effort, and one can easily identify parallel strategies and aesthetic resonances among the six artworks on display. Beyond the obvious use of digital image processing and audiovisual synchronization shared by all artists, the resort to perspectival grids hints at a common wish to open up imaginative spaces beyond the available exhibition surfaces. Another interesting shared trait is the parsimonious use of color: with the exception of Aluan Wang’s “Paths to the Past”, all other works approach limited color palettes with a noticeable caution, obsessing over selected hues (NAXS Corp.) and using them almost as accents (Vibert Thio), or ditching chromatism altogether in favor of an austere greyscale (Ho Him Shun, Kezzardrix + Yaporigami). Even Higa and Kunimoto’s “Dividing a Thing into Hollow and Substance Equally #1”, which most convincingly channels chromesthetic resonances, frames its explosion of saturated colors with the safe minimalism of black and white vistas.

Given the exhibition title, this communal retreat from color seems puzzling and unexpected, and might be interpreted as a subtractive approach to synesthesia, the result of individual attempts at conjuring chromatic perceptions out of synthesized sounds and colorless visuals. The reason might also be more personal – as Ho Him Shun notes,

I guess that I simply got fed up by color in everyday life.

But there is something else left unspoken, a specter hovering around the elongated interior of the Digiark. Five minutes into the chilly infernal descent of NAXS Corp. “XR-XATA-01”, I cannot help but note how the flickering lights at the periphery of my field of vision lead my eyes to focus on the pixelated matrix of the VR goggles’ interior screen: from that moment onwards, I am incapable of looking past the backlit glass surface sitting a few centimeters from my eyes, and the remainder of the work plays out as I struggle to regain a degree of immersion. Combined with the malfunctioning audio, this subtle leak of materiality over mediation will haunt my entire visit, re-emerging with surprising consistence at each encounter with an artwork. Not only are all the artists featured in Chromesthesia Resonance drawing on repertoires of glitches (audio artifacts, visual aberrations, encoding errors, transmedia interferences, hardware malfunctions), but they are doing so with a clear aesthetic purpose, at times even mimicking the effect of analog glitching through digital means to achieve more control over the degree of disruption. And in addition, layered over glitch vocabularies and glitching techniques, are actual, technical glitches challenging the carefully crafted mistakes: is the video freezing on purpose, or is the media player running out of memory? Are these audio stutters programmed in the soundtrack, or are the speaker cones clipping? Why do glitches seem to have colonized this exhibition, and what is their relation to chromesthesia and resonance?

The glitch might have fallen out of fashion. After its appearance in pioneering works of media art, its role in kicking off a fortuitous genre of electronic music and its semiotic codification in internet vernacular, the glitch has paradoxically shifted from a signifier of pure mediation to an aesthetic index of nostalgia. Carefully reproduced and arranged in balanced compositions, different varieties of glitches have become affective devices, referencing the materiality of dead media or granting a veneer of authenticity to uncanny representations. Glitch was about dispelling the myth of digital permanence; it emphasized the ephemerality of data, the incompatibility of preservation standards, and the bit rot threatening reproduction. The nostalgic manufacturing of glitches practiced by media artists is shadowed by the persistence of glitches in the infrastructure of art exhibitions, two almost indistinguishable undercurrents of opposite polarities: one flowing towards an eternally recent past of mediated memories, the other toward arching to the all too present materiality of labor, maintenance, and energy. As Malcolm Harris writes in his recent essay “Glitch Capitalism,” a critical rethinking of glitches is long overdue, especially given how much we today delegate our lives to computation and algorithmic decision-making.

The program fulfills its task without breaking rules, but just because it is fulfilling its task doesn’t necessarily mean it’s doing anything useful; the gap between the two is where we all live now.

Framed as regional examples of experimentation with the synchronicity of sound and image, the six works showcased in Chromesthesia Resonance happen to also offer partial impressions of this gap. How these glitchy undercurrents will reverberate among local audiovisual artists remains an open question.