Browse

Every first Monday of September since 1969, Caribbean Carnival celebrations have turned Labor Day observances into leisurely pageantry on Brooklyn’s Eastern Parkway, its main parading venue. Having first moved from the ballrooms of the Harlem Renaissance to the streets of the old New Negro neighborhood before migrating to Crown Heights post-Civil Rights Movement, the history of Carnival was never any less complicated in the United States than it was in the Caribbean. Nor is its place within the arts, complex at home and abroad, as exemplified by the relationship between the West Indian American Day Parade, as it is now known, and the Brooklyn Museum of Art, to which it was only ever granted but limited access in four decades spent at its doorsteps.

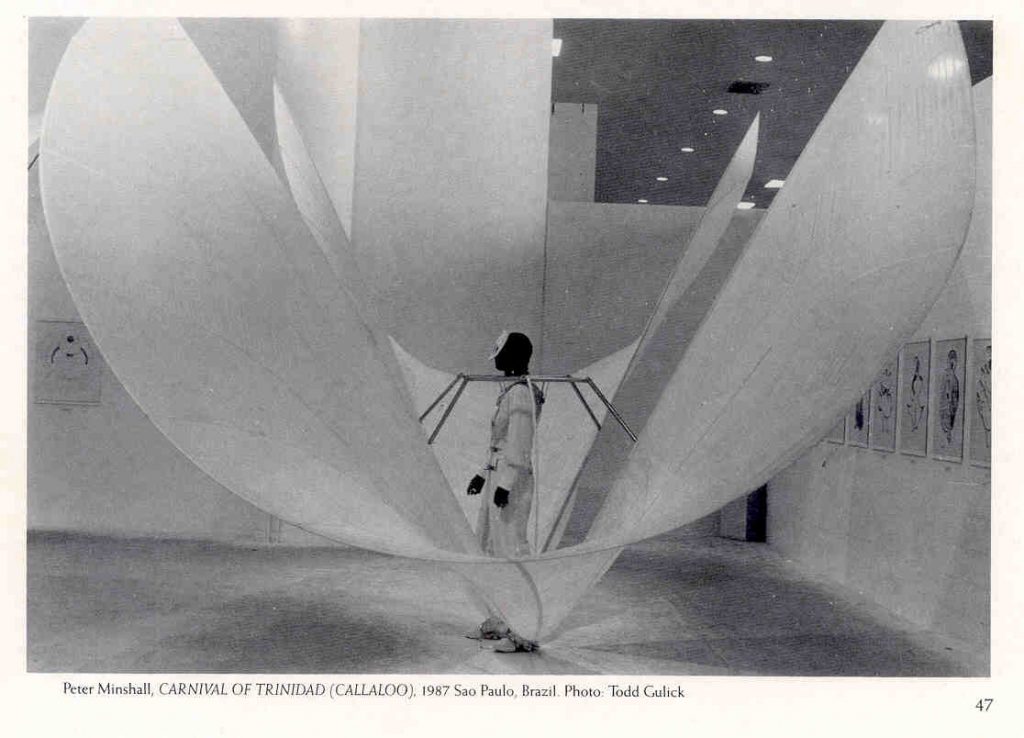

Carnival made a prominent debut at the Brooklyn Museum in 1990 with the exhibition Caribbean Festival Arts, organized by John Nunley and Judith Bettelheim. That exhibition’s discourse and display, however, were largely anthropological, presenting Carnival, along with Hosay and Junkanoo, as folkloric emanations of historical diasporic cultures more so than vibrant artistic manifestations of contemporary global networks.(註1) Carnival made a promising re-entry at the Brooklyn Museum in 1999, under the form of a lecture, “Minshall and the Mas,” and a performance “The Dance of the Cloth,” presented by legendary Trinidadian artist Peter Minshall, a formidable proponent of the recognition of the artistic status of Carnival.

Nearly ten year later, the exhibition Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art organized by Tumelo Mosaka for the Brooklyn Museum though dedicated to “Carlos Lezama (1923-2007), founder of the Brooklyn’s West-Indian American Day Carnival and Parade, a champion of Caribbean Culture,” left Carnival at the door once again. The warning Annie Paul issued in her essay for the exhibition catalogue was not followed: “Caribbean visual art cannot model itself on narrow modernist concepts and tropes without risking extinction”(註2) she wrote, lamenting the reductive Western modernist framework within which Caribbean art is confined. Drawing from notions of the modern, the vernacular and the cosmopolitan, articulated by Homi K. Bhabha as “vernacular cosmopolitanism”(註3) and by Kobena Mercer as “cosmopolitan modernism,”(註4) the Kingston-based cultural critic envisions Jamaican Dancehall as “represent[ing] a vernacular modern or vernacular cosmopolitanism in fundamental opposition to the delicately constructed high modernism of its art world” (my emphasis)(註5). She could have just as well spoken of the Trinidad Carnival, another vernacular modern, in these terms.

That Carnival, let alone Dancehall, should enter the museum is debatable. The question was posed regularly, if ambiguously in most major contemporary Caribbean art exhibitions organized in the United States over the last two decades. The main challenge this question sought to meet was the artistic validation of Carnival, a task traditionally assigned to that great artistic standard-bearer, the museum. The other more fundamental questions about whether or not Carnival should be curated at all and if so whether or not it should or could be curated outside of the museum context and the exhibitionary complex remained largely unanswered.

Taking inspiration from the notion of vernacular modernism as a possible way out of accepted ideas of artistic value and of curatorial principles, artists and curators have yet to articulate questions and make propositions that break away from the dichotomic view of that which can be curated and that which can not, of that which belongs in or out of the museum. “Curating Carnival” presents past and present efforts to address Carnival as an artistic and curatorial object, discusses attending discourses that supported these efforts and offers this author’s own contribution to the debate and practice of Carnival. It does so as part of the discourses and practices of contemporary Caribbean art as well as performance art within contemporary art.

—

Performance art’s positioning within the mainstream Euro-American canon behooves me to ask the following questions: Is performance the last bastion of Eurocentrism in contemporary art discourse and practice? Or, in other words, is performance art a Eurocentric concept? Could Carnival only find its way in the sanctum of performance art by way of Lindsay’s deft deconstruction of the form? And, specifically as regards contemporary Caribbean art: How relevant are terminologies such as “visual art performance” or even simply “performance art” to contemporary Caribbean art anyway? Can Caribbean art offer a platform from which to investigate anew the supposed epistemological difference between the performing arts and performance art?

The quasi-total absence of Carnival within contemporary Caribbean art exhibitions is matched by its near-oblivion from contemporary Caribbean art history manuals. As an example, Caribbean Art(註7) by Veerle Poupeye does devote a chapter to Carnival; however, the thinnest. There are scores of books about various Caribbean carnivals, chief amongst which in terms of numbers of publications, the Trinidad Carnival, followed by the Carnival of French Guyane. For the most part however, the region’s carnivals still need proper historical accounts of their own. More often than not, when considered in scholarly publications, it is within the disciplines of history or anthropology, seldom art history or even visual studies. An exception is Carnival: Culture in Action – The Trinidad Experience(註8) edited by Milla Riggio with a foreword by Richard Schechner, founder and head of the Performance Studies department at NYU, who ushered Carnival into the academic field he created, which might combine approaches from the above-mentioned disciplines, and more.

In the 1970s, following Independence of the British Caribbean colonies, Caribbean artistic performance practices were discussed by academics such as Trinidadian Errol Hill, (1921–2003) and Jamaican Rex Nettleford (1933–2010), Vice-Chancellor Emeritus at the University of the West Indies (UWI), choreographer and founder of the National Dance Theater Company of Jamaica, within the context of the Performing Arts, mainly Theatre for the former and Dance for the latter, against the backdrop of their countries’ blossoming national discourse. Carnival, according to Hill, was to be Trinidad’s National Theatre and, for Nettleford, Jamaica had to have a National Dance Theatre Company. The path to recognition for vernacular forms of expression, artistic or otherwise, was through academic legitimization within known Western disciplines. The exercise often entailed including vernacular content into standard Western form, or using a vernacular form to interpret classical European or American pop music as continues to be the case in steel band, Trinidad’s vernacular musical instrument. Surely, this was considered an improvement from simply not integrating the vernacular into the theatre, dance or music repertoire at all, as would have been the case during the colonial era.

Fast-forward to the 1990s and back to Carnival. From the mid-1990s onwards, Peter Minshall along with Todd Gulick, Callaloo Company’s production manager, began shifting the discourse on Carnival from the Performing Arts and into the field of the Visual Arts, though Minshall came from the theatre, having studied Theatre Design at Central St Martins School of Art and Design in London in the mid-1960s.(註9) Specifically, Minshall and Gulick steered Carnival towards performance art, aided by the concept of mas’ which they helped shape. mas’, short for masquerade, is the vernacular for Carnival in Trinidad and other English-speaking Caribbean countries where taking part in Carnival is to “play mas’” as it is to “rush” in Junkanoo or to “courir le vidé” in Guadeloupe and Martinique. The word mas’ was certainly not invented by Minshall but he appropriated it to refer to “the most visual” Carnival form and, by extension, to his own work, having defined or helped refine mas’ as an artistic genre. Minshall’s 1999 lecture at the Brooklyn Museum was indeed called “Minshall and the Mas” and he is fond of calling himself and being called a ‘masman’, the title of a recent documentary on his work (Masman Peter Minshall by Dalton Narine, 2010). In “Carnival and its Place in Caribbean Culture and Art,” his essay for Caribbean Visions, he writes:

To evaluate the place of the Carnival in Caribbean culture and art, it is helpful to realize that Carnival incorporates a broad range of forms and activities. Carnival in Trinidad includes: lyrical songs (calypso and soca), instrumental music (steel bands and brass orchestras), and costumed masquerade along with the dance and movement by which it is presented (mas’). […] The most visual of these forms is what we call mas’: the tradition of costumed masquerade in the Trinidad Carnival. (my emphasis)(註10)

And goes on to saying, specifically referring to mas’ as “a performance art,” then as “performance” or “performance art:”

Mas is a performance art. It is not merely visual; a mas costume displayed on a mannequin is not mas. […] Though it is performance, mas does not easily fit into the mold of any one of the more conventional performing arts. It is theatrical, but it is necessarily broader of stroke, more symbolic, simpler than conventional narrative theater. It involves dance, but this dance is often more spontaneous than choreographed; or, it is dance that is aimed at articulating the mas that is worn, more than the body that is wearing it. It is most akin to what has become known as simply “performance” or “performance art,”2 yet the mas had these characteristics, naively and unselfconsciously, long before the term “performance art” was coined. (my emphasis)(註11)

—

Space, it has been suggested, not the artwork, is the material of curators, and their instrument the exhibition.(註12) When space is the street, the artwork becomes roadwork, the exhibition a procession, a parade, a march. It is with this understanding of space that with ‘Spring‘ (September 5, 2008), the group procession I organized for the 7th Gwangju Biennale, as a project curator under Okwui Enwezor’s artistic directorship, I offered Griffith the opportunity for his first “full-scale street production”.(註13) Having written and spoken extensively about ‘Spring’, I will turn to Cozier, that expert mas’ commentator.(註14) According to Cozier:

Spring proposed and implemented a trans-cultural, collaborative street procession involving artists from Trinidad, Haiti, Brazil, France and Germany. Through the process of this collaboration, various moments—historical and cultural—were interwoven […]. Tancons has tried to shift the dialogue from anthropological culturalism to comparative discussions with other places (and moments), where similar street actions take place. As a curator of the project, she also entered into the process as imaginer/instigator of the “band” in Gwangju. The line between curator and creative producer became blurred in a transient exhibition space, one without walls and in the public domain. Utilizing the impulse of Carnival, Tancons is advocating another way or mode of curatorship.(註15)

I initially apprehended my role as the organizer of ‘Spring’ and of ‘A Walk Into the Night’ (May 2, 2009) for CAPE 09, the second Cape Town biennial, no differently than I did other curatorial projects, having started to mull over the idea of the procession as a curatorial format at least since Mas’: From Process to Procession, which was to be accompanied by a procession, if not since ‘Lighting The Shadow: Trinidad in and Out of Light’, both exhibitions mentioned earlier which I organized and in which Griffith’s work was featured. Griffith, the main artist in ‘A Walk Into the Night’ went onto organizing a procession of his own, Stuffed Swan (2010), as part of Junkanoo in Nassau. Growing up in Guadeloupe, I had run the vidé in Pointe-à-Pitre through childhood and adolescence. During research trips, I participated in Jouvé in Port-of-Spain a couple of times since 2005, rushed in Junkanoo in Nassau in 2008 with fellow art historian and curator Krista Thompson, gone up and down Arto Lindsay’s trio elétrico in Bahia and paraded with artist Jarbas Lopes and the Mangueira Samba School in Rio de Janeiro’s Sambódromo in 2009. I researched artistic practices and observed the cultural milieu out of which they developed and set out to design a methodology best suited to produce works outside of their original context of creation. I was aided in this pursuit by ongoing conversations with Gulick and it was made possible to a great extent by Anthony ‘Sam’ Mollineau, one of the last recruits of the Callaloo Company and workshop and parade manager of “Spring”. For both my procession projects, I started by organizing what could be seen as a mascamp, barracón or shack, that is workshops during which artists would create works with assistants.(註16) I then proceeded to curate a procession, a parade, a march, taking a measure of space unbounded by walls, reaching back in times immemorial of popular festivals and tuning into a future of globalized mass movements.

Enwezor, who back in 2008 told me that as a Nigerian he knew what a masquerade was, where I was coming from and where I was going, was first to refer to me as a producer in my role as organizer of a procession. At a recent conference, Brazilian art historian Roberto Conduru, responded to my presentation of ‘Spring’ by saying that Carnival already had its curators, the carnavalescos. In turn, Brazilian curator and architecture historian Paola Berenstein Jacques, ventured to say that I was a carnavalesca.(註17)

In Trinidad they would have said maswoman. While the Trinidad Carnival can be seen as having generated not just a new artistic lingua franca, under the form of mas’, but also reinvented an old performative exhibitionary model specially suited for the public ceremonial culture of the Caribbean streets, the procession or parade, the Rio Carnival created it’s own museum-stadium to Carnival, the Sambódromo.

The truth is, I never set out to be a producer, a carnavalesca or a maswoman and the proposition of “Curating Carnival” remains a risky one. Yet to the extent that carnavalescos in Brazil, masmen in Trinidad, Junkanoo-makers in the Bahamas and Crop-Over designers in Barbados continue to make daring contemporary artistic interventions, and artists and audiences throughout the Americas create and participate in Carnival, it remains a necessary one. As contemporary Caribbean art integrates more fully the global contemporary art world and its performance tradition is recognized as being central to it, it becomes an urgent one.