Browse

Rikey Tenn: The Nusantara Archive tends to invite artists from different countries. You have been to Taiwan four times yet this is our first interview. Many questions can be raised regarding the “KANTA Portraits: Taiwan” project, and if we want go deeper based on these entry points. On one hand, the images of the Taiwanese indigenous people – in popular culture or the academic field – can be traced back to the beginning of 19th century, when Japanese anthropologist (Tori Ryuzo) first applied box camera photography on his subjects. On the other hand, we can also see many images of indigenous peoples in popular cultures, such as in commercials, theatres, movies, or postcards. However, these images somehow represent the stereotypes of indigenous peoples mediated by the colonial documentations. This is what Chen Wei-Chi called “photographs of aborigines as colonial archives” in “Photography as Ethnographic Method: The Anthropological Photographic Archives in Japanese Colonial Taiwan” in 2017.(註1)

Jeffrey Lim: Yes… in earlier times, there were only box cameras. They were almost the same process, in which they had to do it on the spot, and processed on plates. And they didn’t have films. It can be either wet or dry plates. Dry plates meant that they could bring them back to the dark room and process somewhere else. Wet plates meant that they were processed on the spot, but usually not far… it happened as well in the history of Malaysia when the Scottish photographer John Thompson traveled to the Far East. From the 1860s to late 1870s he made more than 600 plates on social documentary, from Ceylon, India, throughout Southeast Asia, Indochina, Hong Kong, Macau, China, and even Formosa. All this works independently as his own initiatives.

BT: Yes I would like to further explore this with you, because where we stand determines our vantage point. If the Western-trained photographers (the “imperial gaze”) have shaped our imagination on the indigenous people, how can we develop a different perspective of the indigenous photography in Taiwan? And what makes your practice different from these early practitioners with box cameras? Also, what motivates and drives you to conduct your research in Taiwan?

JL: For one, a lot of photos that existed under Japanese rule were very different from current times; like the attires, even their culture has changed. Because it’s just the circumstance of time, culture changes; it would never stay the same. Looking at colonial archives, and making a comparison with tribespeople now, they will appear different. The thing is, culture always changes, even for indigenous people. If you read the colonial archives for the pictures of the Orang Asli from 200 hundred years ago, they are very different from the natives you currently encounter. In a way it proves the point that culture always reinvented itself, it changes according to circumstance, because of outside influences, e.g. the Japanese colonial period and many others.

RT: Those were one of the few earliest impressions we had about ethnic identity. We never met these people directly, only through the the colonial archive. That is why it is critical to point out: If we are not aware of that we might be influenced by how the colonists saw the indigenous people and their way of looking. Can you talk a little bit about how you see it differently; how your practice is different from those early practitioners who share the same photographic technique? Of course the motivations are different; they served for governmental survey on the territory of the natives, and they have their own academic interests. But how can the process be different?

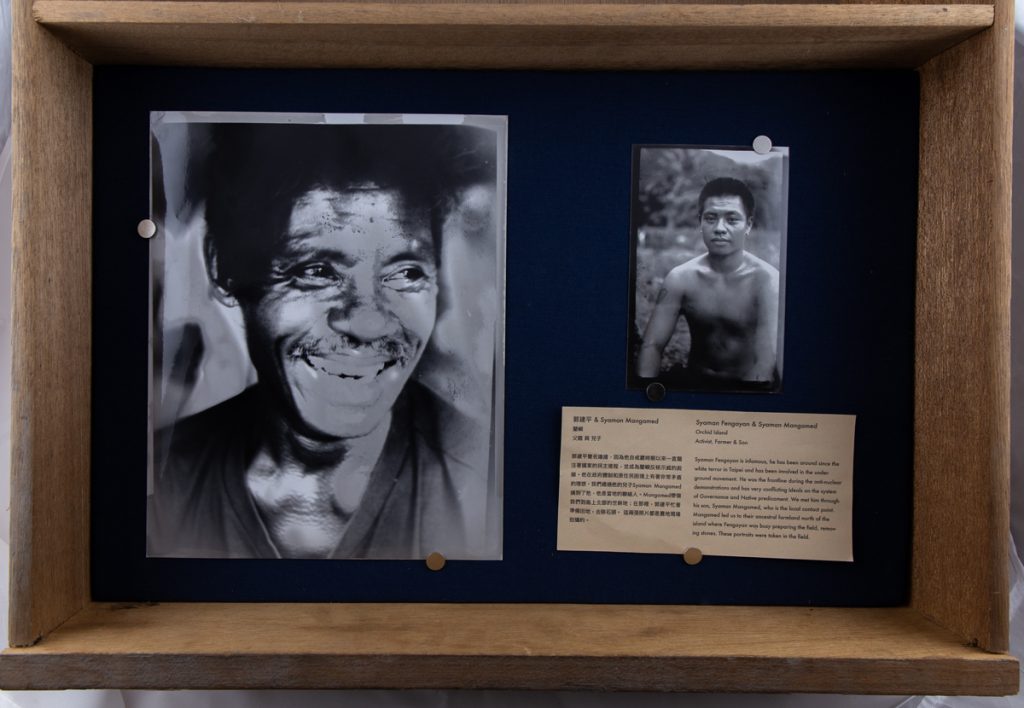

JL: Well, some of the pictures that I’ve taken are in different settings. Take the Tomu (great leader) for instance; I took his portrait three times. First he wore his ‘normal’ clothes, the shirt and pants he uses for church. Then he wore his formal, ‘traditional’ attire. It’s still the same person, but it’s the duality of personalities that he has to live with. Probably another practice is that they keep the original portrait print. This is a very different practice, the silver prints are given to them. And there are also audio recordings. I’m still developing these different dimensions of the different circumstances.

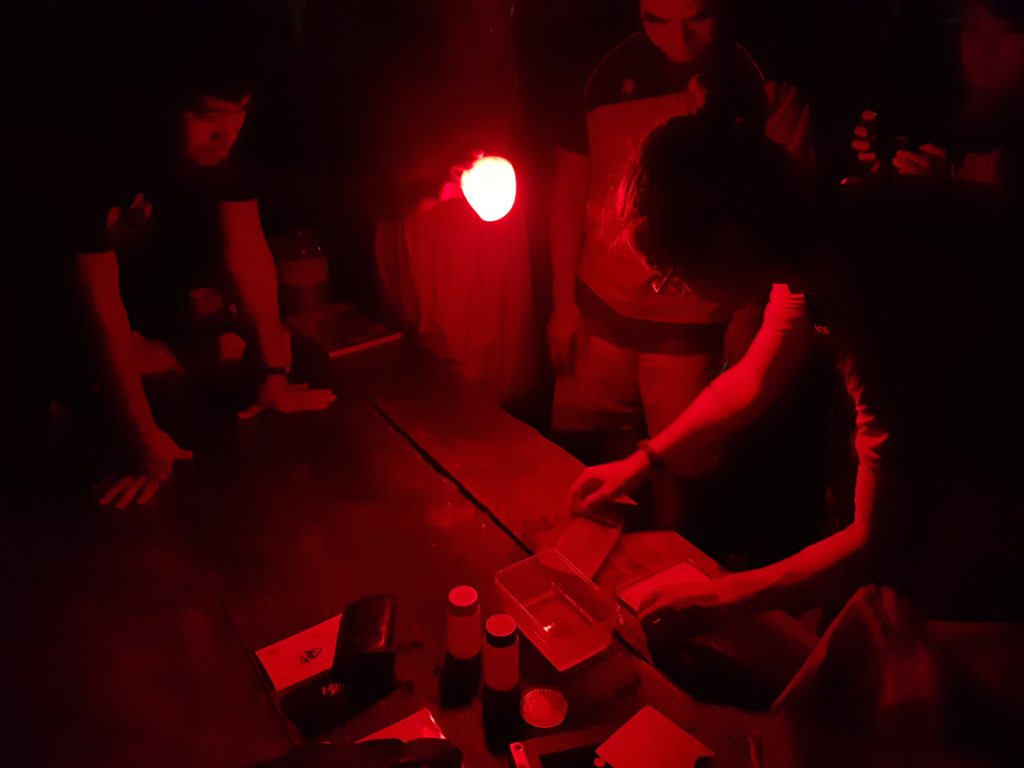

RT: There are many layer processes to your practice, not only to take the photos but also constructing the cameras yourself. You will introduce the box camera and demonstrate it to the tribespeople, you will then develop the photographs, converse with the people who you have photographed, and exchange photos and information with them. You also make presentations or exhibitions. But the audience will only see the end result. They even miss the photos in the drawers in the Petamu Project sometimes. In a project like this, we see that you focus more on the process rather than the result.

JL: For me it is the process, the result is just the by-product, because it actually involves the person to experience the whole portrait and printmaking process. When their portraits were taken, they would see their printed portraits being made, and the print is given to them, that is the real exchange. This experience is important, so the display of the works to an audience after is just the by-product of the process. But I am thinking of not just showing portraits, there are written stories as well. It’s my end result. I’m still exploring how to present the idea or changing concept about anthropology, how I research identities. So, I actually use these portraits, their cultures, and my interpretations of the circumstances as case studies to demonstrate how our ‘traditional’ culture are changing. Therefore it is about exploring these concepts in my process.

RT: It’s interesting to see the nuances between the way you show your works solely and with others. You always choose to collaborate with someone from different indigenous communities. Surely it depends on how we get supported and financed. For me your practice is very intuitive; although you are good in articulating your methods such as photography or other media, you combined varied procedures intuitively when necessary.

JL: It’s very important to collaborate. In Malaysia, I always try to connect and collaborate with someone who knows or is from the community. There is also a social connection between the collaborators – also in order to respect the culture. In Taiwan, PETAMU Project is the first time I actually explored and worked with Posak Jodian, an indigenous artist, especially in a journey of discovery with her. I wish to bring this method back to Malaysia.

RT: If it’s true, then does it matter (when we say) that is Posak Jodian or not? I mean, why we think it’s important to go to certain tribe?

JL: That’s why I am not particular about the tribe. It is the circumstances of the artist from the tribe. Let’s say this project with Posak, the community can be Amis, Pangcah or Atayal. Because the focus is on ‘her’ story with her family and community in Fatáan and in XiaoBitan, how they transmigrate from Hualien to XiaoBitan. It’s not in particular about the photography archive of certain tribe; it’s how they negotiate with time and space. It highlights some ideas of the negotiation, the changes in identities, how tribes sustain their cultures in the changing circumstances or on the very site… Of course Taiwan sets the pretext to my work in Malaysia. In a way, Taiwan becomes a reference point for my work with the tribespeople in Malaysia, and it will be a reference point. It doesn’t need to have the direct anthropological connection. I am interested in cultural links, social circumstances and learning more on how they negotiate. So it makes sense when I apply this again in Malaysia – to find patterns between them.

RT (The Q&As hereafter are conducted during Jeffrey’s residency in Taipei): We see how Japanese anthropologists systematically made the ‘official ethnography’ of ‘the savages(蕃人)’. On one hand, Ino built up the Indigenous categorization using the notion of tribes and divides into Ataiya, Vonum, Tso’o, Tsarisen, Payowan, Puyuma, Amis, Peipo, eight tribes in total on the Taiwan Island – 9 tribes in total If adding Tori’s research on the Yami tribe on the Orchid island. (Comparing to the six-tribe categorization later proposed by Mori Ushinosuke). On the other hand, ‘type photograph’ is employed by anthropologists to form “a critical ethnographic method for knowledge construction“. Taking Ushinosuke’s The Book of Taiwan Savage Tribes, Volume 1 (1917) for example, the categorization is used with photograph attachments of male and female’s headshot or profile from each tribe. Can we prevent such a ‘way of seeing’ of indigenous people when we take photos for the tribespeople? Among Ushinosuke’s categories listed based on the stability and the workability of subjects, ‘physical feature’ is considered to be the hardest to change due to variables of time and environment. If we still use the camera as an empirical tool, does it mean that we will inevitably rely on the physiognomical differences – which may lead to the discriminative or the essentialist understandings of the tribes?

JL: The camera that Tori Ryuzo had first used might be Kodak box camera no 1, which was very basic. Because this was the first available for common users – at that time no one could acquire user-friendly cameras – It is not a professional equipment. That’s the funny thing.

I have a lot of to respond the translations of Chen’s article. To deconstruct what makes their identities, and how they navigate their own identities in present time. (I feel better when this is an interview, because we don’t have time to think too much, and the answers I give are subjective and spontaneous.) My thinking has evolved ever since the last interview we did on Skype in 2018. I went to Southeast Japan island of Shikoku for residency after that, and Posak also finished her video, and we did the exhibition together. This is not what I discuss with anyone because I’m still developing my thinking. The exhibition UNIVERSITAS (2018/12/15 ~ 2019/2/24) directly strikes me to this question. UNIVERSITAS is about the methodology and attempt of how they re-culturize themselves, for me it very much answers this question, because they use the same methodology as the westerners. The camera is just another tool, like all the tools they use for study and categorize scientifically. They use the camera to systematically differentiate. So this is the predicament of the methodology; the predicament is conflicting. When they adopt this from the west, they made the same mistake as the west. The later also colonize, discriminate and categorize using the existed tools.

RT: “From present to historic, although there are changes in the research direction of ethnographic documents, the question of ethnic categorization and the origin of tribes and communities, and the research inclination to comparative ethnology in peripheral island indigenous people are still continuing.” (Chen Wei-Chi) The latest theory of the origin of Austronesian languages from Taiwan is always realized and adopted in many artists’ practices (this is why indigenous tribes become the subject of some art projects in Taiwan). Somehow it also leads to the danger of deliberate explanation of the need of assimilation. This reminds me in 1920s, ‘Malay people’ was believed to be the origin of both inhabitants in Southern Japan and Takasago(高砂). That is also what Takekoshi Yosaburō(竹越與三郎)’s argument in his famous Nangokuki(南國記), when he said the Japanese should know more about ‘the South’ due to “the mix of blood of Malay people in South Japanese people’ vessels.” (Nangokuki, 1910)(註2)

JL: Since I come from a different background, the camera is not the same tool for me. What I use it for has very different intentions from the studies that they did. How they studied is the predicament of ethnography study of culture. They always viewed tribes from their own culture. In that sense they already had a bias, a stereotype before they even started. In the beginning, they called them ‘the savages’, (although I have an issue about this term) – in Europe they called them ‘the barbarians’, because they didn’t live a ‘civilized’ life. They later then called them ‘Takasago’ which showed that they had more respect. But it was still a form of manipulation.

RT: Does it mean that’s why it’s important for us not to follow the existing normalised convention?

JL: Well, we have to question it. The expectation is now, who then are these pictures for? Who then owns the right to this form of imagery? This form of image is just one form of representation. Some of the tribespeople have their ways of dealing with the (visual) forms of themselves in terms of how to represent themselves, through drawing, through pattern making. It’s just different forms. Photography is just the western form of looking. The natives have their own forms as well. In my works, I have already started to bridge other dimension: audio recording. Luc(註3) did the audio and Posak did the video. It’s another medium. We collaborated to look at different representations of cultural identities, not just through the pictures. The pictures are just the end results, but the process was important. When we ask the questions and understand the circumstances that they’ve come from… and the aspects of their identities.

RT: I saw the difference since the ‘light-weight’ sound recording equipment didn’t exist for Japanese anthropologists. So finally we have to talk about the technique, or the medium, I mean technology will affect how we see the subject, and the tribespeople will also adopt it. It interesting how you make these encounters ‘mystical’ again, because you don’t rely on easy tools. Instead, you have a lot of operations: the posturing, the adjusting, the hand lighting, etc, to make familiar things ‘unfamiliar’ again.

JL: Okay. Kanta box is very fresh because they have never seen it before, so it helps create a bridge. They was a reference to ‘materializing’, how I materialize an image of their existence onto a piece of paper. This connection matters, because I present to them ‘a tangible self’. Sometimes they want their portraits taken. This form of representation creates some sort of formality. It’s a form of identity that is recognized by the system / state, because it’s photography.

RT: Definitely it’s the new narrative of our research, since it’s not only about the tribes in different islands, also about the locality, the photography, and the mapping of Nusantara that we share. I believe that there are still many to be articulated in between the representation of photography and the identity recognized by the state, like the way you described.