Browse

“Bahasa Jiwa Bangsa,” a propaganda slogan that emerged in the 1960s aiming at advocating people to use Malay as the national language in Malaysia, resonates Adeline Ooi and Beverly Yong’s findings of Malaysian video art’s inaugural moment (Ooi & Yong 231; Huang 56). Under the term “Southeast Asia,” which embodies the suspension of geopolitical frame, Liew Kung Yu’s mixed media video sculpture titled A Passage Through Literacy was exhibited at the National Art Gallery, Kuala Lumpur in 1989. In the same year, American artist Ray Langenbach’s The Language Lesson, a synchronized multi-channel video installation, was also mounted in the Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), Penang. “Bahasa Jiwa Bangsa,” a political slogan, incidentally summons the motif shared by the content of those video artworks and the trope employed—language (Ooi & Yong 231). Although the term “Bangsa” is interchangeable with “race” or “people,” according to Malaysian Chinese literature scholar Huang Jinshu’s etymological investigation, in 1935, Persaudaraan Sahabat Pena Malaya (Brotherhood of Pen Friends), which did an imitation of the nationalist sentiment from Wilhelm Von Humboldt’s original proposal, proposed “Hidup Bahasa” (living language) as a slogan to construct the connection between the nation and the language spoken by the citizens of the nation.

Indeed, “Bahasa Jiwa Bangsa” can be literally translated into “language is the soul of a nation.” Yet, the fluid meaning of “Bangsa” seems to attract moving images to react upon the sense of internal flux shared by this specific medium and the existing imaginary of a community. On the other hand, the multidimensional referentiality of “Bangsa” also seems to urge moving image to respond to the inner tension when the political-coded words such as “crowd,” “ethnicity,” and “nation” are simultaneously in operation. With the background of working in the theatre, Au Sow-Yee embodies a kind of corporeality straddling between the theatre and movies, which has its historical lineage back to the weighty work of French film theorist André Bazin — What is Cinema? Jacques Rancière has identified films’ politics with the thing “between what is seen in public and precise detailed practice behind it” (Rancière 104). Resonating with Rancière’s definition, Au further utilizes her liminal position between two media and enables herself to dive into how the dynamic negotiation between the seen, the unseen, and the invisible offers various “politics” to engage with each other in dialogue. If the claim of Bazin that “cinema is also a language”(6) is still valid, the motif of “language” Au explored in her solo exhibition titled Habitation and Elsewhere: Image as Instrument does not purely refer to the content narrated by moving images. Instead, this exhibition urgently explores how the mechanism of the narration changes the interrelated meaning of “crowd,” “ethnicity” and “nation” at the moment when the slogan, “Bahasa Jiwa Bangsa,” acquires its voice from the production of music videos, and its exposure is accelerated by pervasive social media sites such as YOUTUBE.

Utterance of Moving Image

As the title Habitation and Elsewhere: Image as Instrument suggests, this project is referred to as a reconstruction of moving images. According to Au, although the three video installations seem to be independent beings, they are contextually interlocked. These three videos are as following: “A Day without Sun in Mengkerang (Chapter One),” “Sang Kancil, Hang Tuah, Raja Bersiong, Bomoh, the Missing Jet and Others” as well as “Pak Tai Foto.” The arrangement of the three echoes what Julio Garcia Espinosa, the Cuban director taking part in the Third Cinema movement, said in 1971, “imperfect cinema is an answer, but it is also a question which will discover its own answers in the course of its development.” Au makes this saying into practice; her ethnographical methods, including interviewing, journal keeping, and excavating, are the primary constructs of her works. Some scenes and sounds in Au’s works even imply the presence of “kino eye,” which further reveals a certain textuality of cinéma vérité. Those implications could be identified in several segments of the self-introduction in the beginning of “A Day without Sun in Mengkerang (Chapter One),” among the off-screen sounds companying the long shot taken from the beach of Melaka in “Sang Kancil, Hang Tuah, Raja Bersiong, Bomoh, the Missing Jet and Others” where the telephone conversation with subtitles in both English and Chinese expose the photographer’s coordinate in real time space, and within the ambient sounds in conjunction with the explanatory utterance toward certain audience sets the interview off in “Pak Tai Foto.” Besides making the sounds and visuals interact by themselves, Au also focuses on the dynamic intervention of intertextuality. Mengkerang, a term with un/familiarity, unhesitatingly inhabits on the soil of those filmed dictated events, nourishing and cultivating this discursive space of actuality via the energy of people’s imagination. While discussing the political dynamics of Indian documentaries, Geeta Kapur, an Indian art historian, has mentioned “the ontological/indexical bond between image and reality disturbed (if not broken), setting off what we might call spectres without footprints crisscrossing the threshold of objectivity” (Geeta 52). In other words, when the interweaving of the materiality of moving images and the fictionality of utterance creates the indistinctive present time, the authenticity of representation gets destabilized and the dialectical thinking becomes feasible.

David Teh, an art historian holding his long-term concern about the geopolitical condition in relation with the screen culture in Southeast Asia, has proposed three theses on the materiality of videos and its distinctively corresponding historical context. He points out, “video is (and is not) Film; video as an oral medium; the long shadow of authoritarianism” (The 30). As Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Mysterious Object at Noon implies, moving images are indeed a mysterious object which not only epitomizes the governance and management of power on the mass but also indicates a messiah historical redemption which Walter Benjamin’s Angelus Novus points to. Take Weerasethakul’s creation practice as an example, the counter-narrative of Mysterious Object at Noon happens to reveal how an exquisite corpse could be presented in the form of narrative. From the north of Thailand to the south, the community comprised of the imagination of storytelling under the real situation composes another section, which provides a parallel time space in the video. The actuality of documentary and fictionality of drama decays one another, leaving the mysterious object which happens to be the collection of Thai native accents. This mysterious object presents the conscious faces of the multitude with rich subjective affections (Quandt 31). Au, in the name of Mengkerang, makes a reference to Malay traditional value of collaboration (gotong royong) to instigate an oral tradition in the form of collective storytelling. “A Day without Sun in Mengkerang (Chapter One)” sharing the same concern with Weerasethakul borrows the Bakhtinian term — heteroglossia — so as to show the original energy in the life experience coming from interpersonal relationships. Compared to Mysterious Object at Noon ending the journey with the open and overflow ocean scene, “A Day without Sun in Mengkerang (Chapter One)” closes at the segment with many seemingly thoughtful storytellers of Mengkerang and the eerie drum beating sound. What should be addressed is whether the reactions of those storytellers put the “gotong royong” re-appropriated by the government rhetoric in perplexity.

“A Day without Sun in Mengkerang (Chapter One)” provides moving images with structure according to sounds. Beginning with two narrators individually speaking in English and Malay, the silent “Wo”(meaning “I” in Mandarin) makes her debut with the help of the subtitles’ content to reclaim her Chinese ethnicity. Because of this characteristic of heteroglossia, viewers circumscribe themselves in the realm of their familiar languages where they vacillate between modes of understanding, watching, listening, and reading in order to grasp information within the flow of lights. Compared to the Hollywood movie industry, which creates the homogenously cinematic experience via the hegemony of single language, Au’s moving images which distinguish viewers from one to another point out that the inner content of a community is in fact the multiple subjects which live heterogeneously. In “Pak Tai Foto”, however, migrant workers with the accented Malay, English and Cantonese dialects not only bring another group of others who live within but also call the ghostly part of the video with the absence of sound resources. The foreign narratives without fluency and felicity echoes to the concept the Iran film scholar, Hamid Naficy, has suggested — the correlation between the accented filmmaking and the diaspora experience. The images of the migrant workers who are uprooted sojourning in the studio of “Pak Tai Foto”, which is located in Petaling Street where Malay Chinese moving southward identify themselves with this memorial site significantly. Two diaspora experiences inscribed upon living experiences move parallel between the two projected screens. At this moment, memory finds its alternative reference point. After all, in the southern peninsula, the edge of this continent, the rooted imagination is not able to translate this broken reality into any readable/structural language.

The Syntax of Memory

Translation is metaphorically compared to cartography in Marc Augé’s book named Oblivion. Augé suggests “every natural language has supplied the world with words (the exterior world and the interior world of the psyche). Here they draw frontiers, but these frontiers do not much from one language to another” (Augé 10). For those who live in a multiracial country, reciting the past inescapably triggers a complicated circumstance. For both narrators and listeners, due to translation, the cacophony caused by the grind of meanings is inevitable. What kind of language is going to express the passage of words called history after all? The experiences of erecting the sense of a nation in various Asian countries are similar after World War II with their successful overthrow of colonial governments. The dictatorship in newly rising nation-states has eliminated dissidents in the name of Cold War, starting another chapter of the reign of terror. Under the government’s control over population’s thought with iron fist, numerous nameless corpses were all over the peninsulas and islands around Bay of Bengal and South China Sea. People in these areas share an even syntax called “the historical necessity of political oblivion” though they speak vastly different languages. As the character Puan Badariah cast by the theater practitioner Jo Kukathas, who also participates in “A Day without Sun in Mengkerang (Chapter One)”, serving in a governmental agency called the Department of Lost and Found, Puan Badariah is in charge of making things lost, but she feels helpless and fearful about the government’s active policy of abandoning the past without limitation.

Puan Badariah is a character with parodical humor, which is the origin of her critical strength. The similar way of narration has also appeared in several semi-documentaries produced by filmmaker Amir Muhammad over the five-year period between 2003 to 2007. The inspiration of The Last Communist (2006) comes from his shock after reading My Side of History, the memoir of Chin Peng, the former leader and prominent figure of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM). In order to compare the whole past of the communist party to the fragments in official narrativeof Indonesia and Malaysia, Muhammad has employed the method of road movie, revisiting Malayan villages and towns where Chin Ping used to stay and composing “a prose on the story of absence in the historical memory” about Chin Ping through interviewing local residents (Muhammad 12). Various backgrounds of interviewees and abundant customs of Malaysian lifestyles in the film are accompanied with tacky and brisk pace of popular songs, bobbing up and down on the surges of the collective unconscious in history. Facing the topography of collective sentiment formed with such historical structure, Au uses images as a cartagraphical instrument, which renders a symptomatic reading as her method, examining and analyzing legends, rumors, folk stories, and other scraps floating down when the official history attempts to adopt living memories into it narratives.

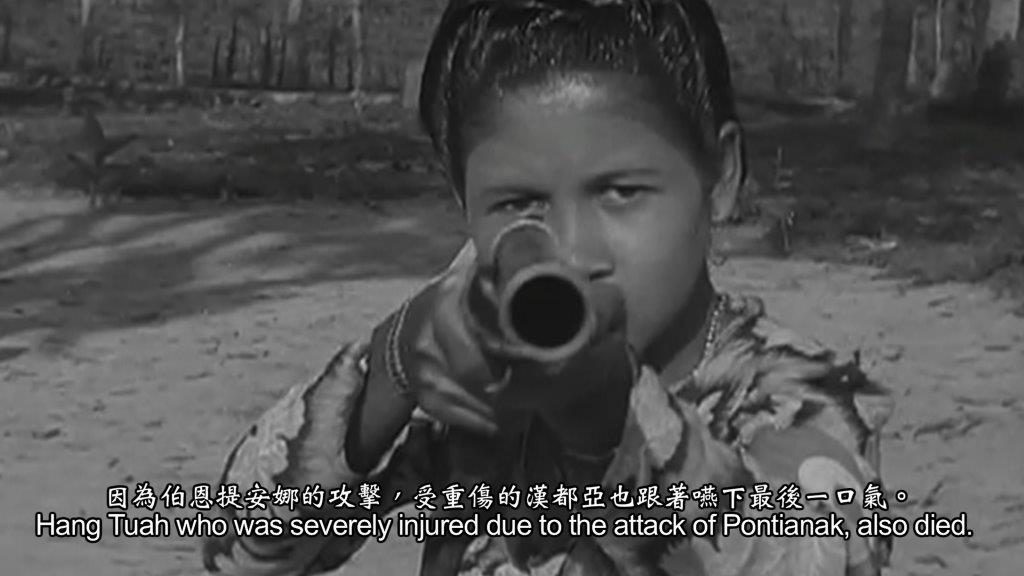

Both “A Day without Sun in Mengkerang (Chapter One)” and “Sang Kancil, Hang Tuah, Raja Bersiong, Bomoh, the Missing Jet and Others” abstract the memories placed still at the bottom of national mnemonic domain, which provokes the memories of growing up as a Malaysian. Textbooks used in elementary schools, fairy tales, legends, and ghost stories told in childhood, as an interpellation, bring Malaysians back to their shared life experiences. These unearthed signs in the form of spoken words are mnemonic codes, ensuring the living experience of personal security and anchoring on the axis of a particular time in the history. However, Au displaces the formula of memory by retrieving-apparatus in these two video installations. The apparatus is converted into a cooperative story-telling chain in “A Day without Sun in Mengkerang (Chapter One)”. The original living experience with the competence of retrieving memory is displaced by popular images in the history of mechanical images in “Sang Kancil, Hang Tuah, Raja Bersiong, Bomoh, the Missing Jet and Others”. The re-assemblage of intertextual perceptron/syntax algorithm can still produce discourse, but its content would be like fractured blocks of signifiers and signifieds, wrapping one’s personal experience into an enigmatically unfamiliar familiarity. The declarations and documents saturated with political implications, the document named Malay Annals (Sejarah Melayu), and its prequel and appendix in “A Day without Sun in Mengkerang (Chapter One)” cannot help but ask what the meanings of the words would be without the fetters upon words and living experiences imposed by national history. Would those just printed words on the stainless paper once look like clusters of images parted from their audio context, glittering vaguely with their fragmental meanings?

Finale

In responding to Benedict Anderson’s discussion on nationalism, Partha Chatterjee, a founding member of Subaltern Studies, has made a crucial inquiry based on his own personal experience as a Bengali: “If nationalism in the rest of the world have to choose their imagined community from certain ‘modular’ forms already made available to them by Europe and the Americas, what do they have left to imagine?” (Chatterjee 521). By pointing out the predominant European-centric perspective as a theoretical constraint of “print capitalism,” Chatterjee reflects upon how the raising of a new nation-state and its synergy of “the anti-colonialism nationalism” further consolidated the asymmetric power structure and privileged the feudalistic figures among the colonized after World War II. Unlike the schematic exploitation of their former colonial mater, Chatterjee surgically distinguishes the spiritual domain from the material domain in order to acknowledge the indispensable project of “modern ‘national’ language” and its instrumental contribution to govern the spiritual domain of the oppressed (Chatterjee 522). In the Bengali region, where Chatterjee’s thesis inhabits, there are two stages of this project called “modern ‘national’ language.” The project was launched by the British colonial government to replace the official language of India from Persian to English and was promoted as the aspiration for Bengali elites. Then Chaaterjee elaborates how English subsequently became part of the paradigm of modernization, especially after the partition of Bengal; in other words, the independence of the state.

Khoo Gaik Cheng, Malaysian cultural and film scholar, has deliberated the cross-references of Chatterjee’s module of anti-nationalism to decipher the ultimate heroic figure in the Malay epic called Hang Tuah. Khoo argues that the character of Hang Tuah has shifted from symbolic currency of the feudalistic society of Malay to a national hero after independence. The specter of Hang Tuah is then able to return via the aura and stardom of P. Ramlee, who is widely recognized as the first superstar in Malay films and can transcend racial boundaries to serve the grander national community in post-colonial Malaysia (Khoo 30). For this reason, we might need to reconsider Habitation and Elsewhere: Image as Instrument, to be an excavation of image ontology, which intends to incorporate the amplitude of those muted figures excluded by the nationalist threshold of listening. By redirecting the issue of the muted figures to the question addressed by Chatterje, Au initiates a topological experimentation of the correlations between modernity and the desire of nationalism in conjunction with the guidance of white noises triggered by the living experience of a multiracial Malay community.

Work Cited