Browse

Living Sound – Expanding the Extramusical (referred as “Living Sound” below), curated by Lai Yi-Hsin Nicole, is a small-scale sound exhibition preseted at the the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Taipei, in its first-floor galleries, and runs from April 27 to July 7, 2019. The exhibition features both Tawianese artists, such as Chiang Chung-Lung and Hong-Kai Wang, as well as artists from abroad, including Australian artist Nigel Brown, Samson Young and Isaac Chong Wai from Hong Kong and Polish artist Karolina Breguła. Among the seven artworks on view, at least half of them are created with the participation of local communities; for instance, Chiang Chung-Lung’s “Nobody Band #MOCA Taipei” is a video installation displayed at the entrance area, created with and performed by the staff members of the museum. “Sweet Minor Keys” by Hong-Kai Wang is created through a workshop with Tseng-Wen Senior Home Economic & Commercial Vocational High School students, who have interpreted the map of sound memories belonging to retired sugar factory employees prior to the beginning of the Madou Sugar Industry Triennial. “Instruments for Making Noise” and “Sounding Symbol: Jian Cheng Junior High School Bell Tower”, to a certain degree, can also be viewed as collaborative works because they both use readymades from the museum and the school building, which was renovated from a historic site.

Out-of-Bounds Music

If participatory art is to be viewed as a form of sound practice, to speak or to voice the sound of “I” is unquestionably superior in terms of politics, and the opposite of this simile will be the loss of sound. In fact, in addition to works created through the collaboration with local communities, Isaac Chong Wai’s performance “One Sound of the Futures, 2016” is also a new version filmed at Liberty Square, which is a collective interpretation with local participants who have answered to the open call. Therefore, whether the audience see the exhibition from the aspect of collectively making sound or from the symbolic aspect of viewing sound/noise in a political light, Living Sound undoubtedly embodies the close relationship between sound aesthetics and politics as well as illustrates it through the local cultural context. In the exhibition space, the curator also quotes the words from Jacques Attali’s Bruits: essai sur l’economie politique de la musique(註1) as a clue to illustrate this viewpoint. However, if we only understand the curatorial motive from the idea of “strange sound” – or more blatantly, “noise” – something would seem to be lacking as the exhibition is clearly different from past exhibitions that have emphasized on sound being a sensory subject.

In the exhibition, Samson Young is the only artist with a professional training in classical music and uses “muted” as an aesthetic strategy. Each work in his Muted Situation series includes a unique design of live sets that prevents the audience from hearing the sound-making sensory object in these scenes of recordings. Comparing to noise, the absence of sound is more like a qualitative change of music, and the approach to understand it is to listen to it as music rather than noise. In other words, perhaps the term “extramusical” used by the curator is indeed the keyword to the interpretation of the exhibition. So, the question we should ask is: What is the “extra-musical”?

The term “extra-musical” is from In the Blink of an Ear: Toward a Non-Cochlear Sonic Art written by sound art theorist Seth Kim-Cohen. The statement displayed at the very beginning of the exhibition Introduction – “Nothing is out of bounds. To paraphrase Derrida, there is no extra-music.” – comes from Kim-Cohen’s discussion in the fourth chapter of the book, entitled “Expanded Practices of Sounds.” Nevertheless, what does “out of bounds” mean? Moreover, why does the author state “to paraphrase Derrida”? The following is the passage from which the statement is taken:

An expanded sonic practice would include the spectator, who always carries, as constituent parts of her or his subjectivity, a perspective shaped by social, political, gender, class, and racial experience. It would necessarily include consideration of the relationships to and between process and product, the space of production versus the space of reception, the time of making relative to the time of beholding. Then there are history and tradition, the conventions of the site of encounter, the context of performance and audition, the mode of presentation, amplification, recording, reproduction. Nothing is out of bounds. To paraphrase Derrida, there is no extra-music.(註2)

In terms of the traditional ways of listening, the “out of bounds” does not conform to the music-listening context; and not being heard implies not existing. However, what is being heard or not being heard is not the symbolic language, but rather a division of the epistemological regime, which involves the entire aesthetic tradition of Western music. In this passage, the author appropriates Derrida’s words, “Il n’y a pas de hors-texte” (There is no outside-text) and replaces “outside-text” with “no etra-music” to deconstruct music.(註3)

As a matter of fact, not only is music deconstructed, when examining the statements of sound artists, we can find ontological views that limit the agency of the auditory sense in both the fields of “sound art” and “music.” Kim-Cohen obviously does not agree with the narrow boundaries of “music-as-such.” He believes that Western musical interval and logic have created an enclosed system of symbols, and those that have been excluded are the different others that defy understanding and are called “the extramusical.” Music’s understanding of itself—in particular that of the Western music—is “inadvertently Husserlian. Though meaning is made in time and as a product of rhythmic and harmonic relations, music as a language seeks to retain its absolute proximity to itself. Any process of difference is thought to occur only within the narrowly proscribed boundaries of music-as-such… This is music’s impossible dream.” Even though later storage technologies, such as the phonograph, have become neutral media for Friedrich A. Kittler, such neutrality nevertheless remains an unattainable transcendence.(註4)

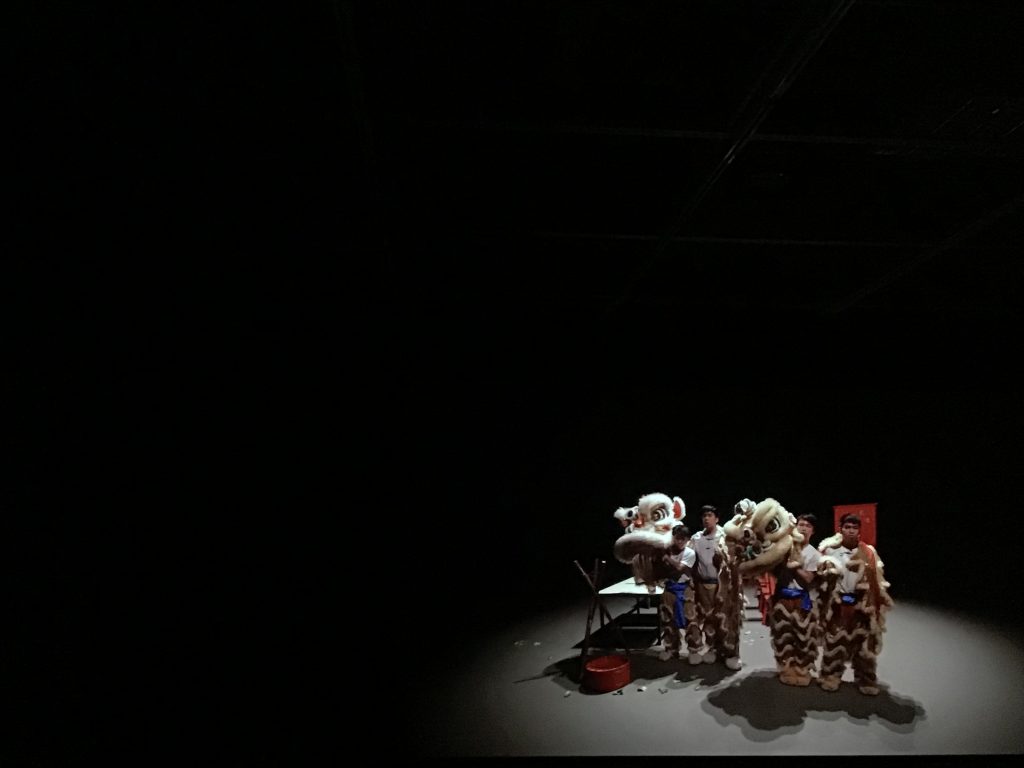

Regarding this line of thinking, Samson Young’s work excellently embodies the music classification that might or might not have meaning. Kim-Cohen quotes Kittler’s words, stating that “‘only the phonograph can record all the noise produced by the larynx prior to any semiotic order and linguistic meaning.’ This technophenomenological attitude has implications for any artistic engagement with sound. Instead of significant sound—sound that functions according to one or another symbolic grid (speech, music, sound accompanying visual material)—the phonograph is a neutral technology, delivering “acoustic events as such.”(註5) Machine is not designed to preserve symbolic sounds, and the sound of “Muted Situation #2 Muted Lion Dance” reminds us of Kittler’s words – “the ums, ahems, coughs, swallows, and hiccups before, between, and around words” – and foregrounds the noises of the lion dancers’ stomping, jumping, rolling or their feet rubbing the floor. The “meaningful” sounds in the lion dance, such as the festive music, the explosive sounds of firecrackers, audience’s cheers or applauses are not preserved; instead, the noises that make “lion dance” real are kept. Additionally, “Muted Situation #7 Muted Boxing Match” even utilizes a freeze-frame from a boxing match to make us realize that these sounds could also be the “sound-in-itself” separated from the context of its making—that is, the transcending imagination constructed by machines.

The Birth of Noise

Can the “sound” that is stripped of its original context still be meaningful? In Karolina Breguła’s “Instruments for Making Noise” and Nigel Brown’s “Sounding Symbol: Jian Cheng Junior High School Bell Tower”, the artists attempt to expand the grids of meaning charactertistic of “musical instruments,” and connect them to their new positions in the changing reality – whether the change is resulted from history or other reasons. The collaborative work in “Sounding Symbol: Jian Cheng Junior High School Bell Tower” involves the museum’s bell tower and its history – it was part of the school building in the period of Japanese rule – and the artist invites students from the museum’s neighboring school to wrap sixteen mallots with personal messages before using them to sound the bells. The production of sounds connects the past and present while transferring the symbolic meaning from an authoritarian past to the democratic present. Also related to the same space, “Instruments for Making Noise” converts remainders from past exhibitions into an array of musical instruments, incorporating aesthetics into politics. By allowing and encouraging audiences to borrow the instruments for demonstration, music exceeds the border of performance and enters a new (political) domain.

The musical instruments as “the remainder of exhibitions” seem to beacon an invisible border; the remnants are outside the border. Kim-Cohen stats that “sound art, as a discrete practice, is merely the remainder created by music closing off its borders to the extra-musical…Unlike sculpture, and to a lesser extent, cinema, music failed to recognize itself in its expanded situation. Instead, it judged the territory adopted by the expansion as alien and excluded it tout de suite. The term ‘sound art’ suggests the route of escape, the path of least resistance available to this errant practice.”(註6) It is in the intersection of “sound art” and “music” on this route of escape that we witness the option for “the extra-musical” be anti-musical or participartory in a diverse way, reversely expanding the realm of sound aesthetics and the practice of listening.

Both the karaoke videos of “Nobody Band #MOCA Taipei” on view at the entrance of the exhibition as well as the workshops and memory map of “Sweet Minor Keys” are examples of using production tools and the production process to re-consider sound practice. Their shared topic perhaps can be: how can individuals that have production tools (of a specific field) can create collective sounds? In these sound practices that focus on collaboration, both the museum staff advocating the equal rights to same-sex marriage and high school students majoring in restaurant management, who are not yet viewed as part of the labor force and are invited to design a song list for local memory, are given a certain degree of authorship; yet, this does not mean that the authorship of the artists disappears. Instead, their authorship becomes the final creator of “sound and speech as media and products that are interactive” –“treating music and sound as a formative method to fabricate the public site and body politics.”(註7) However, to communicate meanings has always been the primary function of music, which people have largely forgotten. Through these works, the curator’s avoidance of the term “sound art” also seems an approach of critiquing essentialist or “pure” sound creations.

In the contemporary aesthetic regime, where does the boundary between sound and other media lie? Who has the final say, the curator or the actual participants? Isaac Chong Wei’s “One Sound of the Futures” might have provided us a route for discussion. The artist does not consider himself a sound artist, and states that the artwork does not aim to create a “permanent monument” but to “transform hundreds of participants into standing, speaking sculptures.”(註8) Although the word “sculpture” is used in a metaphorical sense to mean the material, but as the practitioners of sound art have started to move from the symbolic to the real, can we then classify Chong’s work as sound art simply because it shares a foundation that manifests a growing similiarty to that of sculpture? A more extreme example, of course, would be the massive protest against Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Bill participated by more than a million people on June 9, 2019; and the other lage-scale demonstration on the 16th even reached two million protestors, exceeding the number of people in any political protests ever taken place in modern history. When a scoeity can make such astonishing “noises,” do we need artists to negotiate the sound of the “future” for us?(註9)

The answer to this question perhaps lies in the scale but the boundary maker of the noises. I am therefore reminded of Attali’s discussion of the origin of noise and its relation to ancient sacrificial rituals, which might be validated in a tragic way. However, even though we do not need artists to represent us or negotiate the “future” for us, does it mean that we do not need composers anymore? The answer is precisely the contrary. We will always need them to create music or extra-music because when political mobilization takes place, we can always detect the existence of the extra-musical.