Browse

V. Photography in the Field

Today I’d like to photograph the customs of the savage community, and gather both male and female savages around. I heard this old man is in his 90s; the purpose was to ask about the old stories of the Amis community.(註1)

– Tashiro Antei, 1896

How do anthropologists take photographs? If the photographs left by the Government of Formosa were taken by the military photographer, and Ino Kanori just used photographic archives as a method of ethnography without taking photos by himself, then what is the process performed by the anthropologists with their own cameras in the field? What makes photography accountable in the field? Namely, how have photography become an ethnographic method in the field?

In October 1896, Torii Ryuzo, who was conducting a field research in Eastern Taiwan had written a letter to the Tokyo Geographical Society to give a progress report with details about photographing the ‘savages.’ The letter goes:

The savages in Eastern Taiwan, except for those who live near Taitung, have not been entirely sinicized, hence we are allowed to discover the original appearances of the savages today. They are genuinely the research subjects which interest us anthropology researchers the most. I realized that the savages in Eastern Taiwan are not afraid of being photographed at all, so the photoshoot went smoothly (The underline was added by the author).(註2)

Because of Torii Ryuzo’s intentional use of the camera in the field, the firsthand pictures of Taiwanese indigenous peoples taken by him in the initial years of Japanese rule could serve as an example to elucidate how anthropologists photograph in the field and to discuss archival methodology generated in photographic records during fieldwork.(註3) Before coming to Taiwan for his first field research, Torii has recognized the importance of field photography as archival records. As a result, he has been consciously taking photographs during his fieldwork in Taiwan ever since.(註4) After going back to Japan, he also displayed the photographs taken in the field that illustrated the cultural features of Taiwanese indigenous peoples while presenting the research results of Taiwan at the Anthropological Society of Tokyo and the Tokyo Geographical Society.(註5) In his published paper, he even used the photographic records as the materials for comparison and analysis purpose; he has published a photo album which consists of ethnographic images related exclusively to a single community (entitled Yami on Orchid Island).(註6)

When Torii first came to Taiwan for research in 1896, it happened that the Government of Formosa had a research plan on Eastern Taiwan’s migrant area ( “colony” was the term used back then) as well. The investigator who was in charge of this Eastern Taiwan research was the Department of Agricultural and Industrial Affairs technician Tashiro Antei (田代安定, 1857-1928). Before Tashiro Antei came to Taiwan, he has already joined the Anthropological Society of Tokyo in 1889 and has taken a position as reporting director in the Tokyo Geographical Society. Upon his arrival, Torii applied for a research permit from the Government of Formosa; meanwhile, the Government of Formosa was in the process of appointing Tashiro Antei to Eastern Taiwan; as a result, Torii Ryuzo and Tashiro Antei departured from Taipei together to embark on the first field research on Taiwan. During their stay in Eastern Taiwan, they often went on explorating the tribes side by side.(註7)

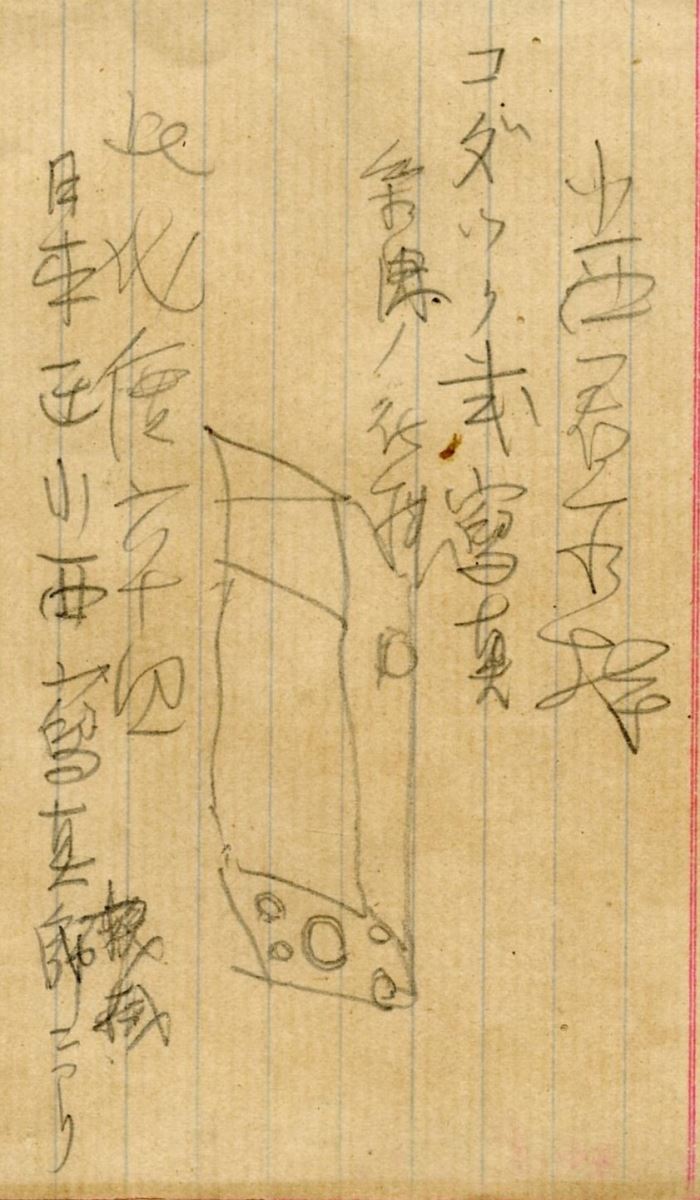

Tashiro Antei, the Department of Agricultural and Industrial Affairs technician who accompanied Torii Ryuzo left multiple records in his field diary of Torii photographing local indigenous tribes in the field. He even left a sketch of the camera in the said diary. In《臺灣雲林高山蕃支族語 (Tribal Languages Spoken by the Savages in Yunlin Mountain, Taiwan )》, the language research and documentation notebook in which Tashiro retrieved from his field research and put together in a military base in Milun Mountain when he went back to Hualien Harbour in October 1896, a sketch of photography equipment was found that is highly considered to be the one carried by Torii.(註8)

Tashiro noted the camera equipment as “コダツク式寫真,” which would be the Kodak box camera (Fig. 12). Torii wrote in his memoir《某老學徒的手記 (Notes of an Old Novice of Sorts) 》that, back then, sketching was the most used method to document images instead of using cameras in the field of Archeology and Anthropology in Japan. He reckoned that sketching was not enough when doing field research on Taiwanese savage, so the recording had to be done with a camera. However, he did not know how to photograph at first; hence, he borrowed a camera from the university to quickly learned photography, and then brought an incomplete set of photography equipment to Taiwan. In the memoir, Torii said with confidence:

In the academic field of Anthropology, Applied Photography begins from me.(註9)

What Torii did not mention is was the type of photography equipment that being brought along. Through his companion, Tashiro Antei’s field diary, there is a way to possibly know about the photography equipment Torii used in the field. Mori Ushinosuke was Torii’s assistant on his fourth exploration in Taiwan; he has written in remembrance of the scene where Torii was carrying a box, which was supposedly the portable storage box for the box camera.(註10)

Tashiro Antei who kept Torii’s company in the field founded the Taiwan Society for Anthropology with Ino Kanori in Taipei only a few months earlier. Though his exploration in Eastern Taiwan from August to December in 1896 was to execute the Government of Formosa’s plan called “The Compilation Plan of the Colony”, he managed to not only investigate the required area from the planned colony as well as the geography, geology, industries, and the agrarian relations of Eastern Taiwan, but conduct ethnographic and linguistic researches.(註11)

The importance of the field notes and diary Tashiro left lies not only in the fortuitous sketches of Torii’s photography equipment used in the field, but also, which is even more essential, his multiple entries on the happening when Torii was photographing local indigenous peoples during his explorations in Taitung and Hualien. For example, on October 7th, 1896, in Puyuma community, Tashiro wrote in the field diary:

After ten, arrival at the Aboriginal Office, just like yesterday, asking the Rikavon communicator about the savages. I went back to the dormitory at twelve.

At half past two, going to the Amis community, to the Chief’s house. Torii also came along. Towa and Yasui came together as well accompanied by the Rikavon communicator. Take photographs of the chief’s family and the community residents (真影ヲ寫サル.(註12)

Tashiro Antei, Torii Ryuzo, and the Aboriginal Office officers who came along, Towa and Yasui went together to the Amis and the Puyuma community (the Malan Amis in Taitung in the present day), accompanied by the Rikavon communicator. Upon their arrival, with the translation by the Rikavon communicator, Tashiro gathered the chief’s family and a few indigenous peoples in the community to took their photographs. Tashiro’s field diary left the records of the written conversation with the chief assisted by the local communicator. Tashiro wrote down the words below to show the communicator and asked him to help gather people from the tribe not only for the photoshoot but also for the investigation the originating legend of the Puyuma and the Amis as well as their customs accordingly:

Today I’d to photograph the custom in savage community and gather both male and female savages around.

I heard this old man is in his 90s; the purpose was to ask about the old stories of the Amis community.

Ask him about how many years has the Amis been founded here.

Ask the name of the ancestor of Amis.

Explain what he means in great detail.

Let him know that you can help with this. Thus, translate what he says completely, no matter what kind of contents he answered, please let me know the details.(註13)

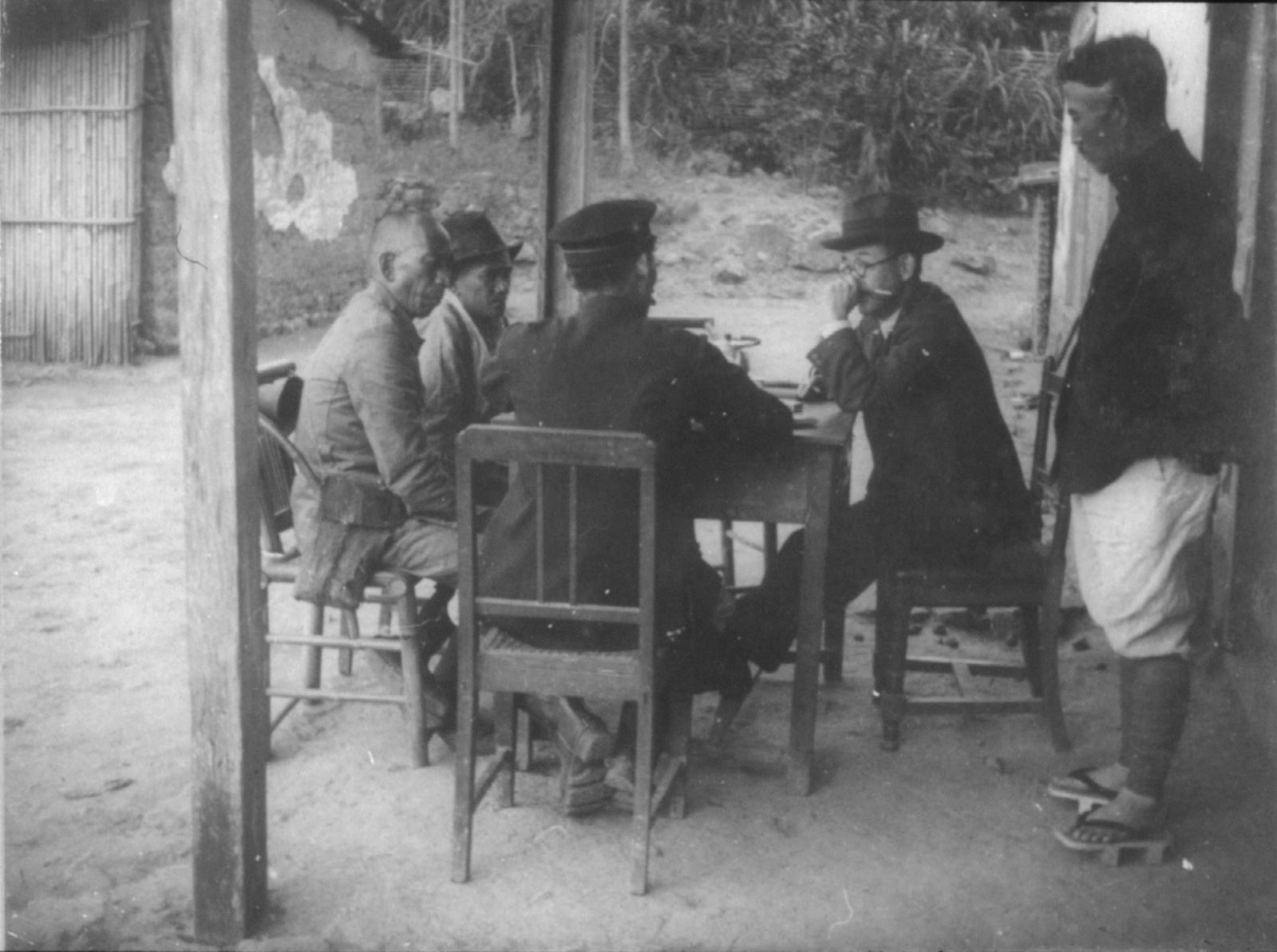

Tashiro’s diary documented the written conversation with the translation by the communicator with an elderly man from the Puyuma-Amis (the squatting one, first from the right in the front row in Torii’s photograph (Fig.13), retrieving the originating legend of the Puyuma-Amis, history of migration, customs of the community, and tribal relationships with the peripheral Puyumas. The section about “Southern Amis” in the thesis Torii Ryuzo published in《東京人類學會雜誌 (The Journal of the Anthropological Society of Tokyo)》in the second year was based on the field notes on that day.(註14)

On November 24th, 1896, which was a sunny day, Torii Ryuzo seemed to be feeling unwell physically, but still, he went with the group to Nanshi community and took photographs in Cipawkan in Hualien. In Tashiro’s diary, he wrote:

Leaving Hualien Harbor’s military base in the afternoon, Shinozaki and Karasu arrive at communities in Nanshi. Torii feels unwell, so the subject he chooses to photograph today is the two elderly men from Cipawkan. Photographs have been taken.

It was already four when leaving the community after finished.(註15)

In addition to photographing tribal indigenous peoples’ physical and cultural features, Tashiro also documented how Torii photographed the Takao Harbor scenery as they took the shuttle boat from Hualien Harbor that sailed north along the west coast on 13th December. Tashiro left two entries in the diary:

13th December, sunny

Leaving from Hualien Harbor

Heading back to Taipei by taking Chiyoda Maru that sailed along the west coast15th December, sunny

Arriving at Takao Harbor at 4:30 before noon.

Torii is photographing the scenery.(註16)

In the letter which Torii Ryuzo sent to the Tokyo Geographical Society during his field observations in Eastern Taiwan, he mentioned: ”the savages in Eastern Taiwan are not afraid of being photographed at all, so the photoshoot went smoothly.” Indeed, he left a large quantity of the glass plate negatives; it looked like things went smoothly in the field. However, in Tashiro Antei’s dairy, there were a few intriguing entries as well. For example, around November 17th, 1896, the locals raised complaints when Tashiro went to the Cikasuan tribe in Hualien to investigate. Tashiro left a record of the written conversation with the local savage tribal communicator Lin Chen-Lao with the help of his tour guide who came from Hualien Harbor, Lin Feng-Yi:

(Tashiro Antei) I have no idea what the communicator was thinking about and what caused him to advise me not to deliver the medication.

(Lin Feng-Yi) The former Japanese lord had fallen ill after the photoshoot. Rumor has it, according to the savages, that Japanese has unleashed the ghosts. Thus, the communicator informed the lord of this matter that the medication is not doable.(註17)

The “Japanese lord” mentioned in the written conversation record should be Torii Ryuzo who had been carrying the camera and taking photographs everywhere in the field. The savages put the blame for the physical unwellness after the photoshoot on “Japanese unleashing the ghosts”, being cursed, or the dark magic fueled by the box (the camera) brought by the Japanese lord. Throughout the world history, there are some similar complaints made against cameras for being falsely thought to be a satanic installation that would suck the soul out of the photographed subject or unleash curses.(註18)

The moment Torii happily wrote down “the savages in Eastern Taiwan are not afraid of being photographed at all, so the photoshoot went smoothly” on site – with regard to the photographs we see today in Torii’s thesis and monograph as well as the glass plate photographs that are later re-developed and re-published in the 1990s of which subjects are the images of indigenous peoples that are the end products of the archival process of photographic records, the process of compound translation into the written conversation in the field; the photographed subject’s fear towards “Japanese unleashing the ghosts” seemed to be blocked by the auratic effect that reappears and reconstructs the history and culture resulted from the given terminology entitled by anthropologists or through the reproduction of the visual content of images under different cultural contexts in different eras.

From the view of anthropology, if the archival process of the photographic records in the field in the early years of the Japanese rule period are shown as Torii’s experience – accumulating first-hand photographic records of Taiwanese indigenous peoples in a short period and getting ahold of physical and cultural features by establishing a standard type so as to conduct comparative ethnographic researches. Then, how does the process work in the mid-to-late Japanese rule period? How does the field research go and how to photograph images accordingly especially after the Taihoku Imperial University established in 1928, showing the fact that an academic institute for Ethnography research, which is rarely seen in Japan, had been built in Taiwan?

Miyamoto Nobuto, the assistant of the Institute of Aboriginal Ethnology, Department of Literatures and Politics in Taihoku Imperial University wrote in his memoir《我的臺灣時代 (My Stay in Taiwan) 》about his field photography experience when he first went on exploration in the Orchid Island in remembrance. In the summer of 1929:

Exploring the Orchid Island… for me, as the teaching assistant of the Institute of Aboriginal Ethnology, I take menial chores on my shoulder, and photography is one of my main duties. Back then, we did not have the 35mm Leica camera that is widely used now. We also did not have films. The thing we brought to use was the cabinet-type glass-plate assembled photography equipment that was normally for business use and the wooden tripod. I was a beginner photographer then, so I also prepared a set of equipment that could develop dry plates and a portable darkroom made of a roughly 2 meters long square-shaped, mosquito-net-like satin weave. The stuffiness and hotness during daytime there make people feel drowsy; still, I managed to take quite a few photographs.(註19)

The investigation on Orchid Island was to set up spots in different tribal communities to collect genealogical information, measure physical anthropological features and take photographs. Such investigations were carried out with the help of the assigned police from the police department stationed in the tribes, which was a shared experience in terms of the first fieldwork experience conducted by the Institute of Aboriginal Ethnology in Taihoku Imperial University one year earlier.

In July 1928, Professor Utsurikawa Nenozo and his assistant Miyamoto Nobuto who were in charge of the Institute of Aboriginal Ethnology in Taihoku Imperial University went to Hualien, and, after getting the permit to enter savage territory from local police institutions, start the investigation there with the help of the local assigned police. The group entered the 立霧溪 (Liwu River) basin accompanied by the police who led the way and the worker who carried the luggage.(註20) The Tabito community in Puyuma was the destination of Utsurikawa and Miyamoto’s first Anthropology field exploration. In the house of the Chief of Toboko, with the help of the assigned inspector, Tomabechi’s translation, they interviewed Chief Umin Urai and documented the seven generations from the Chief’s genealogy in memory with a total of 230 names. The next day, with Inspector Sato’s translation, they interviewed Chief Raushin Bakkule in the neighboring Kubayan community, and collected his genealogy with a total of seven generations and 382 names.(註21) IAmong largely documented genealogy files, information about the original place of the communities, the migration, the marital relationships between tribes, and having either close or hostile relations are revealed automatically. The first fieldwork in 1928 inspired Utsurikawa Nenozo, and Miyamoto Nobuto to develop the “Taiwanese Indigenous Peoples Familial System Research” plan which got the funding support from the Government General Kamiyama Mannoshin three year later to conduct a holistic research. In the end, they published a historical and sociological ethnography entitled《臺灣高砂族系統所屬之研究 (Taiwanese Indigenous Peoples Familial System Research) 》that are based on the massive database of genealogy and later won the significant honor in the Japanese academic field – The Japan Academy Award in 1936.(註22)

Since Miyamoto Nobuto came to Taiwan by the end of the 1920s, indigenous community had already undergone profound social changes under several decades of colonial rule. The research subject Mori Ushinosuke mentioned when explaining the research methods in 1912 would be easily changed due to the surrounding environment and the process of group interaction. When Miyamoto Nobuto entered the “savage territory”, what he saw was a changing indigenous society and culture or one that has changed, to be exact. Yet, only the physical features and the coincidental result — the genealogy that can trace back to many generations — discovered by Utsurikawa Nenozo and Miyamoto Nobuto in the field stayed unchangeable comparatively. In other words, “memory” and “physical features” became important research subjects in Utsurikawa and Miyamoto’s fieldwork. When Utsurikawa and Miyamoto collected genealogical information in the tribes in savage territory, they also took photographs of each community.(註23)

The reflection of environmental change can also be seen in the fieldwork conducted by colonial anthropologists. In the era of Ino Kanori, Torii Ryuzo and Mori Ushinosuke, the documentation or images of them doing fieldwork in the tribes could always be found. However, going into Utsurikawa Nenozo and Miyamoto Nobuto’s era, Japanese police department had stationed locally in the tribes, so the fieldworks were often done with the help of the assigned police in measuring physical features, collecting spoken genealogical information, and photographing within the confines of the savage territory where both the entrance and exit were controlled. If comparing the scene where Torii Ryuzo squatted down at the riverside of Xiuguluan River documenting what was happening in 1896 to the one where Utsurikawa Nenozo sit behind the desk with the police officer and his assistant on both sides, the indigenous peoples being interviewed in front of them in the hallway of the tribal police station in 1930s, it is clear that, these two images portrayed the different situations which field researchers faced in the field in each period in term of the intensity of the colonizer’s savage controlling policy and the colonial anthropology in field environments. (Fig. 14, 15)

Regarding the anthropology fieldwork conducted at the early stage of Japanese rule, Ino, Tashiro or Torii often asked the tribal chief about the situation concerning the savages through the help of local communicator in the Aboriginal Office or local offices. However, in the 1930s, police assigned to the savage territory had already penetrated deeply into the tribal communities. From the communicator to the police, the person responsible for assisting onsite translation and guidance have changed, especially when there are also police officers coming tribal community in the savage territory.(註24)

Meanwhile, in the aspect of using field image as an ethnographic method, the Institute of Aboriginal Ethnology in Taihoku Imperial University also used camera equipment and left more archival images resulted from anthropology fieldwork. Despite that, the problematic of the origin of human race that was raised from the early stage of colonial anthropology in Taiwan remained ongoing but gradually changed from ethnographic information of lingual and physical features to that of genealogy in terms of the orientation. From natural to social, from observable to memory-related, and from the present to historic, although there are changes in the research direction regarding ethnographic information, the issues of ethnic categorization as well as the origin of tribes and communities, and the research orientation of comparative ethnology related to indigenous peoples in peripheral island remain consistently motivated.

VI. Conclusion

The forming of the photographic archives of Taiwanese indigenous peoples can be viewed as the product resulted both from the ethnography authorized by the aboriginal management administration and the use of photography as an ethnographic method in modern Anthropology.

Photography as a fieldwork method has initially been a witness to the historic event of the start of aboriginal management administration in the colony’s official ethnography; nonetheless, it also left series of critical event-centered indigenous photographic documents beyond the colonizer’s intention. The photographic method in relation to colonial anthropology in Taiwan applied in the fieldwork gradually developed through Ino Kanori, Torii Ryuzo, and Mori Ushinosuke either by means of in-person photoshoots or using photographic archives. What is more crucial is that the scientific standard of the unbiased empirical method was the longstanding core value held by Ino Kanori, Torii Ryuzo, Utsurikawa Nenozo and Miyamoto Nobuto when collecting onsite ethnographic resources in the field – focusing on the importance of being at the site and on the scene to collect and photograph images of indigenous peoples with a clear problematic; between photography and the knowledge of anthropology, the photograph becomes a representation of fact, a method that properly presents the authenticity of indigenous peoples who were being observed.

The photographic experiences in the period of Japanese rule meant not only the photographic records for the purpose of governing indigenous peoples, but also the archival sources for representing the construction of ethnic categorization in anthropology through ethnology-based photographs. After the 1990s, the retained image archives has become the resource of which photographic meaning could be reappropriated and reproduced so as to embark on a new photographic social life under different space-time contexts both in Japan and Taiwan that had entered into a new era.(註25)

(Editor’s note: the author of this article is a doctoral candidate of the Department of History, New York University, USA, a Ph.D. student at the Department of History, National Taiwan University.)