Browse

There’s a mountain of bricks. It spreads out like a flower blossom. It stretches to the sky, to devour the sun. It is very far away. It looks ominous and fearsome. It pretends to be a pure and flawless being, as soft as a child’s palm. Before it disappears, the wall bulges and changes shape, as if it knows that when it falls it would be an astounding sight to behold.

– Tong, Rak Ti Khon Kaen (2015)

Rak Ti Khon Kaen, translated to English as “Love in Khon Kaen”, begins with the sound of a big military truck arriving at a school in Khon Kaen, which is now a makeshift hospital for soldiers affected by a sleeping disorder. Due to having bad dreams, the government had to import sleeping machines which were effective in promoting good dreams in American soldiers in Afghanistan.

Aunt Jane, alumni of this elementary school, walks with canes to visit her childhood friend, who is now a nurse in this makeshift hospital. She sells knitted dolls to soldiers’ relatives and accidentally became the volunteer who takes care of Itt (which means “brick” in English), a soldier from southern Thailand who sleeps in Aunt Jane’s childhood classroom. Meanwhile, Keng, a maiden, full time as a salesperson for the rubber cream, part time as a medium for the government, volunteers to connect with soldiers’ spirits for their relatives.

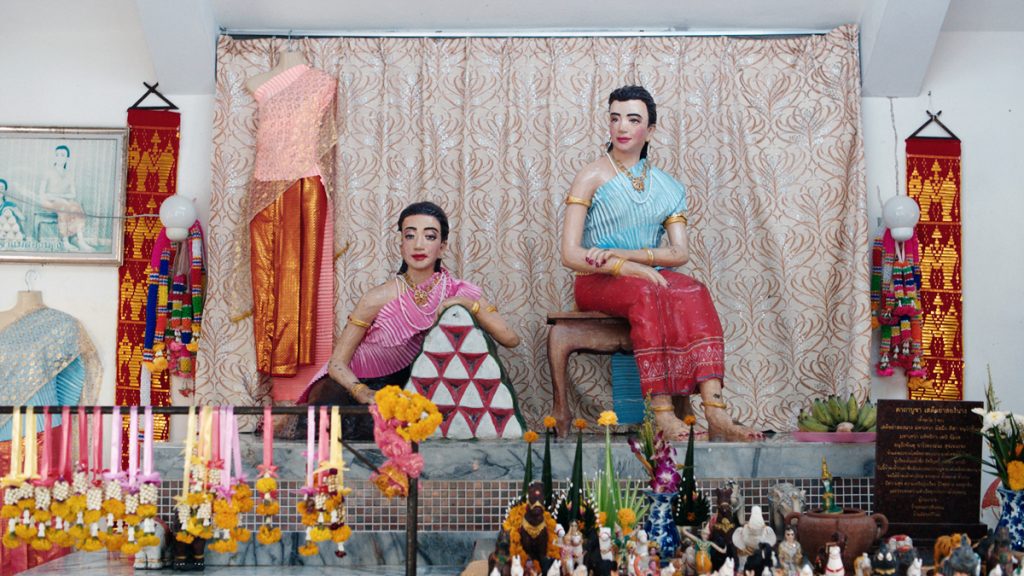

One day, Aunt Jane eats longans in the public shelter in a dinosaur garden near her intimate friend’s workplace. She later finds that the Two Sister Princess’s spirits come to join her. They warn her that those soldiers will not fully wake up, because their souls are taken by the ancient kings, and have become their slaves to fight in the never ending war.

Rak Ti Khon Kaen tries to question the concept of sovereignty (meaning the right to use violence with impunity) devolved from metahuman beings to actual human beings. It can be found in many tribes, where arbitrary orders are given only during rituals in which human beings impersonate gods, but those who give the orders are not the gods, so the sovereignty is contained in time. Those vested with sovereign powers during the ritual season are no different from anybody else.

Divine kingship, in contrast, would appear to be largely a means of containing sovereign power in space. The king has total power over the lives and possessions of his subjects; but only when he is physically present. As a result, varied strategies are employed to limit the king’s freedom of motion. Yet there is at the same time a mutually constitutive relation between the king’s containment and his power: the very taboos that constrain him are also what render him a transcendent metabeing.(註1)

The sovereignty in Rak Ti Khon Kaen enacts with the color blue, the sky, and the ancient kings’ spirit. It is widely known that after the abolishment of its power in the 1932 Revolution, throughout 1947-1957, royalists tried to restore monarchical power. Especially the coup in 1957 which resulted from the triumvirate between the US government, the royalists, and Sarit Thanarat (whose portrait is in the school hall). The Thai ruling elites considered communism incompatible with the Thai way of life, given that Thai society was traditionally attached to the monarchy and Buddhism.(註2) The US government under Eisenhower approved the glorification of King Bhumibol Adulyadej as the father of the nation as part of the anti-communist psychological strategy. During this period, many parts of Thailand hosted US military personnel and equipment during the Indochina wars.(註3)

During Sarit’s premiership, Isan’s economic underdevelopment was construed as a political ‘‘problem’’, for popular discontent might lead to support for the communist insurgency. The Northeast Development Plan was drawn up in 1962 on the World Bank’s recommendation.(註4) Sarit’s first meeting to prepare for the Northeastern Development Plan was in Khon Kaen Province.(註5) Therefore, Khon Kaen Province, besides being the place where Apichatpong grew up and gradually formed his memory, it has also been a place of conflict, scramble and neo-colonialization from the Thai state.

The Sky is questioned by Apichatpong. We see characters wearing blue garments in the scene where a gigantic paramecium floats in the sky. Sky god is worshiped by many people who speak Kra-Dai languages in Southeast Asia, for example the ancestors of Siam and Lao who worship Than or Phi Fah long before adopting Buddhism and Brahmin from India through Khmer and Mon.(註6) This contrasts with people who speak Austronesian languages (i.e. Moken in the southern part of Thailand) who migrated from Taiwan around 4,000 years ago. They still worship the spirits of their ancestors, even though some have converted to Islam.

Is Tai Dam’s Than God (which is from 天Ti’en in Chinese)(註7) the origin of divine kingship? Than may resemble sovereignty but it is not contained in space; on the contrary Than is contained in time, because the sky power transcends through mediums limited by time. The medium has no power to command other than in the ritual temporality. Sovereignty in Tai Dam society lingers with time instead of space or position. Then, when has sovereignty in the Tai-Kadai ethnic group become transcendent? Nobody knows, and the answer may not be necessary.

The challenge with sovereignty can be found everywhere in Rak Ti Khon Kaen which is an oneiroid landscape with the monster in the lake resembling a castrated or impotent phallus. The patriarchy is ridiculed in a scene in which Aunt Jane, Keng, and the nurse sneer at a soldier’s erected penis. Imaginary Khon Kaen is the anti-oedipal/electra world which attempts to question the lack of phallus, and challenge the grand narrative in which the male sex is represented by the big tree spreading its branches and roots.

She patriotically admires the soldiers and earns a living with low income jobs without questioning the Thai state’s hierarchy. If we conclude that Aunt Jane may be seen as an object (slave) in the concept of the Thai state’s subject/object (king/slave),(註8) it may be too easy to conclude. In the Rak Ti Khon Kaen universe, we can see her transformation from object to subject, her use of herbs which defies modern medicine, and her trying to inquire about sovereignty. She is finally trying to widen her eyes to end this vicious and dreamy cycle.

Rak Ti Khon Kaen shows us a world where masculine power and sovereignty are hidden under the rhetoric of innocence. It appears beyond (dirty) politics, but is actually fragile and sensitive to criticism. Rak Ti Khon Kaen reminds us that in the unconscious/dreamy world and experiencing another world through films, we begin to understand what Aunt Jane said to Itt after he took her on a tour of the Invisible Palace: “Now I see everything clearly that the heart of the kingdom, besides the fields, is nothing else.”

Rak Ti Khon Kaen presents us with other types of love which are not love for the nation-state or love for sovereignty, it is love because it feels lacking. Like the fear of being castrated (in males) and envy for the penis (in females), Rak Ti Khon Kaen presents us with love and desire that transcends nationality, gender, age, class, human and the non-human. Rak Ti Khon Kaen encourages us to love the ghosts of common people and immanent ghosts, because love is not fanaticism or the taxonomic classification of things.

Itt told Aunt Jane that he actually wanted to sell Taiwanese style bings, before he fell asleep again. This represents the transition of the slave state. He dreams of living a different life. Trying to question military authoritarianism is the subjectivity. The subject is a state of semi-sleep and awakening rather than mere awakening or sleeping, because the subject has the potential to become anything. The subject is like a ghost. It allows the body to be exposed to multiple effects by waking up while we are asleep.

This might explain the state of semi-sleep in Rak Ti Khon Kaen and the attempt to wake Itt and Aunt Jane. Even if they are eventually being put to sleep again, at least sleep allows us to imagine other possibilities in space and time. It’s also an encounter with the unconscious.

Rak Ti Khon Kaen‘ reminds me that nightmares are things that do not move on. The nightmare is the attempt to free oneself from the fixation, which does not exist, of the individual and collective problems from which sovereignty pretends to be divine. Nightmares are something that must be faced, and not to be escaped by using machines which facilitate good dreams. Even if it is trying to make us be obsessed with dreams forever.

When I was alive, I always daydreamed about sailing in the sea. Leave the military uniform on the shore. Let the waves engulf your body until it is part of the sea. Until there are enormous white waves trying to pull me back to shore. You have to listen. Every wave that hits shore is filled with the cries of the people who died in a war that never even happened.

Some Ghosts on Bodo Island

Itt’s desire to escape from being a soldier and Aunt Jane’s wish to wake up from a nightmare seem to be the same as the story told by former army officer Aki in Bodo (寶島大夢, 1993), a feature-length film by Huang Ming-Chuan(黃明川), delivered through vignettes that are reveries. It is similar to a memory in Itt’s notebook which Aunt Jane secretly read, about a trip to Kaeng Krachan, and the painful stories of the Red Shirts, the grassroots political movement since 2006 protesting against military dictatorship and aspiring to improve democracy and overcome inequality,(註9) and Ah Kong’s imprisonment. Ampon Tangnoppakul commonly known in Thai as Ah Kong, was charged with section 112 of the Criminal Code of Thailand, and was later found dead in the Khlong Prem Prison mysteriously.(註10)

These are similar to the stories in Bodo, which at times tells the love triangle between Aki, Yisan, a deserter, and Ganghua, a woman who sells her body in order to meet her alleged communist father, who was abducted by Kuomintang(國民黨; as known as KMT) soldiers and has been imprisoned since Kanghua was a child. Other times, Bodo portrays the empty and desolate houses of the Austronesian indigenous peoples; who were brutally exterminated during the White Terror.

Bodo appears to be a reaction to the end of Martial Law which controlled Taiwan from 1949 to 1987. Martial law began shortly after the ROC government retreated to Taiwan. Before that, there were already several violent clashes between the Taiwanese people and the KMT party soldiers. Especially violent outbursts, including the February 28, 1947 massacre, which was considered the origin of the white terror. The incident resulted in deaths estimated between 5,000 and 28,000.(註11)

It is known that under the White Terror period and the presidency of the party, KMT received direct assistance from the US government. In 1950, President Harry S. Truman announced that the US government would not provide military assistance or advice to China in its invasion of Taiwan. In the wake of the North Korean invasion of South Korea in June 1950, the US government considered this as the first global threat of communism. President Truman then issued an order to the fleet protecting the Taiwan Strait which implied support for the KMT Party’s regime. The US government has provided Military assistance to KMT through the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) from 1951 to 1978. The US government provided various military assistance to Taiwan, as well as through the military advisory agency “Military Advisory Assistance Group” (MAAG) headquartered in Taipei.(註12)

Bodo(寶島) is the Taiwanese-dialect nickname for Taiwan; it means Treasure Island, another name is Formosa Island, which was named by the Portuguese in the 1500s, Taiwan has been a strategic point that the Western and Eastern world powers have been vying for about 400 years. A group of Austronesian-speaking peoples who have traveled to the north of Taiwan around 6,000 years ago, then spread throughout the island to the south, and left Taiwan around 4,000 years ago, later arriving in Southeast Asia islands,(註13) including the southern part of the Thai state.

Bodo is also the name of a nomadic male character, a person who mediates with ghosts, in the south of Taiwan. He became friends with Yisan’s father, who was separated from his child for ten years and wanted to meet Yisan. He later found that Yisan had escaped from the barracks concurring with the mysterious death of Captain Huang, which we later found was accidentally killed by Yisan. Aki was involved in the investigation and found Captain Huang’s notebook which is full of imaginative pornography. After that, Aki started having nightmares. Images and sounds from the notebook reverberate in his head, as if his libido was unexpectedly released.

If Rak Ti Khon Kaen was an attempt to undermine military dictatorship and patriarchalism, so was Bodo, through its various lame male characters. Because there is no real battle, the army is therefore a defense against internal battles rather than external ones. Taiwan is therefore covered with sluggishness and dreariness. The slow pace of life reveals a lust which is concealed under the military uniform. Dreams and the diary are therefore areas of affective emancipation.

The nomad first met Yisan’s father at a long, penis-like boulder. A father who wants to meet his lost child. Aki wants to learn about the secret life of Captain Huang through his notebook, because Captain Huang had a relationship with Kang Hua whom Aki secretly loved. Aki always wanted to be manly and Don Juan, like Captain Huang. Aki’s desire formed the Oedipus complex. But in the end, he fails when he finds out that Kanghua likes Yisan. On the contrary, the father seeking his son is like the opposite of the Oedipus complex.

Bodo is therefore a resistance to the Oedipus complex. It metaphors the ruins and fall of the patriarchy. The reverse side of the Oedipus complex offers us to explore the architecture of the abandoned fortresses and the nightmare. The father looking for his son, and returning to being a child once again. Wandering and singing enabled Yisan’s father to return to his childhood and connect with the nomadic self.

The encounter between Yisan’s father and Bodo who later died under Aki’s hand; the brief encounter between Yisan and his father, and the encounter between Yisan and Kanghua and their eventual separation, these immanent relationships were meetings destined for separation. These were not meetings because of lacking, but rhizomatic and corporeal assemblages.

The state resembles a relationship that never existed at all; it is a fortuitous confluence of elements of entirely heterogeneous origins (sovereignty, administration, a competitive political field, etc.) that came together in certain times and places, but that is very much in the process of once again drifting apart. Therefore, the state is a matter of assembly and collapse rather than a fixed state. Like sovereignty that can be created and destroyed.

The anti-Oedipus presents us with the shattered identity of Taiwan via a nomad who knew Aki’s secret, the youth who escaped the influence of the military, the remnants of indigenous houses and abandoned fortifications, and a ghost that possesses Bodo and Aki’s dream. Therefore, Taiwan is a landscape of intense anti-identity where it rejects the essence, and is a body that squirms away from hierarchical control.

Martial law in Taiwan has been lifted for over thirty years, but the nightmare of communist annihilation has not faded. Taiwan’s history and transitional justice are complex. KMT’s reluctant efforts of “Buying peace”, compensated the victims’ with money, but it cannot erase the truth of their atrocities. The victims’ relatives want more than just compensation and a democracy which gives citizens the right to vote representatives. They want acknowledgement of KMT’s unjust and serious legal action, including the cessation of the KMT’s monopoly of power.

Most Taiwanese only care about the present (think of the scene in Rak Ti Khon Kaen when Keng tries to look at the sleeping soldier’s past life, but his wife told Keng, “Why look at the past? Please look at the present.”) They care only about their family and having a job and making money. The past is the past, and after the end of martial law, the leader of the KMT Party had only apologized to the past and redeemed themselves by compensating the victims, which was not enough because it was merely a postponement. Taiwan will not be able to move on. The actions of the KMT will still haunt them, unless serious consideration is given to the past through legal efforts and promoting transitional justice.(註14)

Even though these two films are from different regions, they are interconnected and resonate with one another, and offer a critical reflection on traumatic history. Wounds and nightmares are not easy to deal with. They will continue to haunt the modern world, the world that emphasizes moving forward. But how do we stride? Because the past has the power both to confine the present, and make the present bewildering for us to think about.

Past/Ghost with permanent hierarchical power, situated transcendent animism, and a god-like ghost transforms into a nation state. Hyper-royalism has metamorphosed into believing in a government, coup leader, or nation-state. This transcendent ghost seems to be what these two films inquire about and challenge. At the same time, these two films illuminate us with the multiplicity of feral ghosts, the ghosts of lost ancestors, indigenous spirits, and the ghosts of disappearances enforced by the state. Both films invite us to think about the potential horizontal meshwork of revolutionaries via entering into the abyss of (bad) dreams by watching these two films. Because we wake up for a chance to dream, and then we dream for the upcoming awakening. Yet we watch films to awaken once again.