Browse

That Year

In 1927 (2nd year of the Showa era), the Taiwanese Cultural Association, a driving force of the Taiwanese democracy movement and culture, split into left and right wings and underwent reorganization. The right wing of the association formed a separate Taiwanese People’s Party. Founded in Japan, the Taiwan Minpo (Taiwan People’s News), which for a long time represented public opinion in Taiwan and reported on various social movements, gained approval for publishing in Taiwan on condition that a Japanese edition also be published. The newly formed left anarchist organization Taiwan Black Youth League was denounced and forced to disband due to large-scale track-downs and arrests by the police. The Central Bookstore, which was endorsed by members of the Taiwanese Cultural Association and had the ambition to become a hub of cultural exchange and dissemination of knowledge in the central region, commenced operation. Moreover, in the same year, Taiwanese Chang Wo-chun, who was a student at the time, founded Youth Taiwan with friends in Peking (Beijing). The poet Yang Hua was suspected of violating the Maintenance of Public Order Act, and the writer Wang Shih-lang was arrested and imprisoned for forming the Taiwan Black Youth League. The novelist Yang Kui discontinued his studies in Japan and returned to Taiwan to join the Union of Taiwanese Peasants. Yeh Tao, who was a teacher at an elementary school at the time, resigned from her post and joined the peasants’ movement. The revolutionary Hsieh Hsueh-hung formed the Taiwanese Communist Party in Shanghai.

One might say that there are some sorts of research results which show that every time we try to account for the minute historical details of a given year, various people, events, and matters that are (seemingly) associated with each other always appear. Taiwan in the 32nd year of Japanese colonial rule is no exception. In this historical background, where literature and politics were intertwined in the context of lively but highly repressed democratic developments and social and cultural movements, let us first turn to a historical scene that focused on the development of Taiwanese arts (fine arts).

Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition

Let us try to picture the opening of the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition in a venue at Kabayama Elementary School on October 28, 1927. At 4 p.m. that day, there were already 10,000 visitors, all attired according to the dress code and crammed before the works. Some of them tiptoed only to see heads before them blocking their sight of even the frames of the works. The administrative staff were sweating heavily as they toiled away printing tickets that were quickly sold out again and again. The catalogs and postcards prepared for sale during the ten-day exhibition period were almost sold out in one day. What made the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition such an exhilarating event?(註1)

This was the scene on the opening day of the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition in Taipei according to Yen Chuan-ying. But it does not look quite the same as the social climate just mentioned, does it? Events like this, aimed at creating an aesthetic experience and attracting wide public participation, took place twice in 1927: One was the first-ever Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition. The other was the public voting of the “Eight Views of Taiwan”. Both were artistic, cultural, and educational events promoted by the Japanese colonial government based on its experience of cultural governance in Japan and colonial Korea. The history of the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition should be a familiar one in the context of the historical development of Taiwanese arts. There were a total of 16 exhibitions organized by the colonial government. The first ten exhibitions were organized by the Taiwan Education Association. It was suspended in 1937 due to the outbreak of the second Sino-Japanese War. Later, it was organized by the Bureau of Culture and Education, Government-General of Taiwan and renamed “Taiwan Governor-General’s Art Exhibition”. Many Taiwanese painters whose names we are familiar with today, such as Chen Cheng-po, Chen Chin, Liao Chi-chun, Kuo Hsueh-hu, and Li Mei-shu, were among the winners of multiple awards at the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition and Taiwan Governor-General’s Art Exhibition. It is worth noting that, in a time when art education and relevant specialty schools were lacking in Taiwan, the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition and Taiwan Governor-General’s Art Exhibition can be said to have been the most important cultural events influential on local developments of fine arts. This special educational model, in which exhibitions preceded institutions (art museums and research institutes) was directly mentioned in Tateishi Tetsuomi’s “On Taiwanese Fine Arts”:

The government’s attention to fine arts in Taiwan by far exceeded its attention to plastic arts, literature, music, drama, etc. Its partiality to fine arts was unmatched. It was called the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition when organized by the Taiwan Education Association. Later, when it became the Taiwan Governor-General’s Art Exhibition, which foundation was more solid, it continued growing in scale…. However, in consideration of administrative matters, if one wishes to use fine arts to improve Taiwanese culture and cultivate the Japanese imperial spirit in colonial subjects or foster outstanding native artists, then there are some priorities before holding a festival-style art exhibition.(註2)

However, this idea was not realized. Arts education under colonial rule had to have priorities. The Government-General of Taiwan regarded art exhibitions as “cultural elixirs”. Under this premise, it is unclear whether the Taiwan Governor-General’s Art Exhibition actually nourished “ideas and enjoyment of beauty” or yielded instead a “tool of social education” and a “cultural display window”.(註3) However, I reckon, speculation about the intention of the high-ups was not the primary concern of the artists at that time. Given the lack of academic roles in arts and the market, selected works in exhibitions received not only public attention on platforms approved by the government but also the most substantial financial support: The award-winning works in government-organized exhibitions would be purchased by the government at a prize equivalent to one year’s worth of living expenses.(註4) In this uniform but comprehensive system, painters at the time can be said to have simultaneously benefited from and contributed to exhibitions—needless to say, such a game of artistic cultivation would lead to many limitations to the subject-matters of artistic creation. In other words, in 1920s’ Taiwan, the new cultural movement supported by the government was one of fine arts (especially painting) and not literature. Pens representing critical voices of society were bound to be repressed, while paintbrushes drawing landscapes were praised and promoted. What kinds of landscapes were being drawn, though?

Artificial Landscapes and Local Color

When appreciating landscapes in Taiwan, it is necessary to consider Japanese perspectives for comparison.(註5)

– Kinichiro Ishikawa

Any discussion of Taiwanese landscapes in the 1920s cannot be complete without mentioning Kinichiro Ishikawa. This painter loved sketching and was an important driving force of the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition and Taiwan’s fine arts education. According to his landscape tenet of “viewing Taiwan from Japan’s eyes” and the “local color” that he frequently emphasized in his essays, he seemed to be about to embark on a landscape appreciation tour in search of differences in the “southern country” with his viewfinder. In 1927, the show of a “journey in search of landscapes in Taiwan”, which can be said to have been scripted collaboratively by painters and the colonial government, was officially staged and called for public participation.

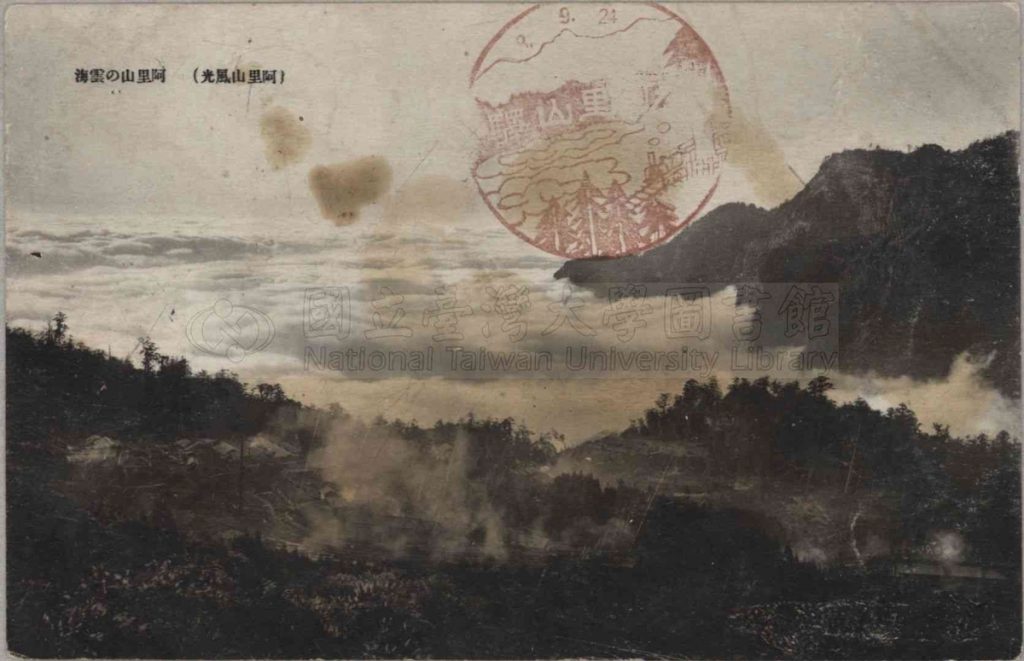

Around the time when the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition was being organized, the Taiwan Nichinichi Shinpo (Taiwan Daily News) simultaneously held the “Eight Views of Taiwan” voting event. This event, which can be called the first public voting in Taiwan, was derived from the successful experience of the “New Eight Views of Japan” voting launched in Japan in the same year. In the imperial imagination of the time, this public voting event, which purported to discover Taiwan and was marketed by mass media, sought to improve identification with Taiwanese culture through the charm of national landscapes, thereby demonstrating the abundant achievements of colonization. However, public voting was not so simple, and politics was not absent in the neutral matter of landscapes. In the 2nd year of the Showa era, the “New Eight Views of Taiwan” were eventually chosen by government-assigned “insightful people” from the short list of 20 “landscape candidates” that received the highest votes (public voting accounted for 30% of the final results, while the review committee accounted for 70%), so as to ensure that the results would fit the image of the “southern country” under Japanese Imperial Culture. The “insightful people” that constituted the review committee included not only the person-in-charge of the steering group (Makoto Kinoshita) assigned by the Government-General of Taiwan, but also reviewers from the Bureau of Culture and Education, Bureau of Transportation, the transport industry, media, and the arts and culture industry, as well as promoters of the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition such as Koto Gobara and Kinichiro Ishikawa.(註6)

According to the announced criteria, in addition to local characteristics and historical value, convenience of transportation, possibility of developing into national parks and public recreation centers in the future, and their even distribution around the island had to be considered for the Eight Views of Taiwan.(註7) The voting rules were simple: After purchasing ballots made of ehagaki (a collection of pictorial postcards) or machine-made paper, voters were required to write down their address and name alongside the name of one “view”, then mail out the ballot or bring it to the polling station in person. Only one view could be nominated per vote, but a person could vote unlimited times. Within only one month of voting, Taiwan Daily News had received as many as over 360 million votes.(註8) It is not hard to imagine that in the eyes of both the people and the government, the voting event—endorsed by the Government-General of Taiwan—was not only an election of landscapes but also represented a hope for local tourism industries and economic development. The final results, I believe, are familiar to every Taiwanese:(註9)

The Eight Views of Taiwan: Basianshan (or Eight Immortals Mountain; Taichung), Cape Eluanbi (Kaohsiung), Taroko Gorge (Karenkōshi, present-day Hualien), Tamsui (Taipei), Shoushan (or Shou Mountain; Kaohsiung), Alishan (or Mount Ali; Tainan), Sun Moon Lake (Taichung), and Keelung Rising Sun Hill (Taipei)

The Twelve Wonders: Baguashan (or Mount Bagua; Taichung), Grass Mountain (present-day Yangmingshan)-Beitou (Taipei), Jiaobanshan (or Jiaoban Mountain; Hsinchu), Taipingshan (or Taiping Mountain; Taipei), Dairikan (Taipei), Daxi (Hsinchu), Musha (or Wushe; Taichung), Hutoupi (or Hutou Pond; Tainan), Shitoushan (or Lion’s Head Mountain; Hsinchu), Xindian Bitan (or Green Lake, Taipei), Wuzhishan (or Mount Wuzhi; Hsinchu), and Qishan (or Qiwei Mountain; Kaohsiung)

Special Sites (special selections): One sacred space: Taiwan Grand Shrine; and one soul mountain: Niitakayama (“New High Mountain”, present-day Jade Mountain)

Whose Mountains?

Mountains, forests, railways, lakes, ports, lighthouses… in response to the need for industrial development and the colonial economic infrastructure, these facilities became government-certified national landscapes, part of the bucket list of every tourist in a fortnight: In the summer of the 2nd year of the Showa era, the imaginary landscapes were officially materialized in Taiwan. Among these tourist attractions, which are still familiar to the public today, mountains were a popular landscape choice. It was not surprising for Taiwan, known as a “Takasagun” (“country of high mountains”), to elect multiple mountain views. It is just that the travelers who had visited these mountains many times in the past—before such kind of journey passed from being imperial adventures to popular daily recreational activities—were mostly the military, the police, anthropologists, and occasionally, painters.

The “indigenous boundaries” on high mountains had been surveyed; the entire territory of Taiwan had been conquered; and “mountain landscapes” were no longer the only use for the results yielded by “Shokusan-kogyo” (encouragement of new industries). Mountaineering activities seem to be a natural outcome of these developments.(註10)

Still in 1927, the Railway Department of the Government-General of Taiwan established its “Road Improvement Section”, thus commencing the period of road improvement in Taiwan. It not only promoted the addition of government-owned train routes and vehicles, but also transformed the road between Su’ao and Karenkōshi, present-day Hualien, which was a footpath for police-executed punitive expeditions against indigenous peoples, into a highway.(註11) This year saw the publication of Numai Tetsutaro’s Brief History of Taiwanese Mountain Climbing, which was reputed as the harbinger of modern Taiwanese mountaineering history, as well as the first issue of Taiwan’s Mountains, the periodical of the Alpine Association of Taiwan. The Alpine Association of Taiwan, which had just celebrated its first anniversary at the time, consisted mainly of Japanese government officials and individuals from high society, and occasionally organized various lectures and exhibitions related to mountaineering culture. Interestingly, Kinichiro Ishikawa, who participated in the establishment of the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition and the voting of the Eight Views, made his presence felt again—he was a secretary of the society and the designer of the society’s logo.(註12) Let us not forget that Kinichiro Ishikawa, who claimed that “Taiwan has the best landscapes of Japan”, was also the painter who followed the Nantou police into the Central Mountain Range in 1909 (42nd year of the Meiji era) and sketched the “landscape” of a punitive expedition along the defensive line on the indigenous boundaries.(註13)

Tourist Landscape

Landscapes are sceneries. What we praise as a landscape must have something distinctive. Only places with the best sights can be called landscapes.(註14)

– Banka Maruyama

How is a landscape created? Where does a sightseeing tour begin? For those who travel around Taiwan today, are the sites they see an imaginative geography of colonial history or everyday scenes of contemporary tourism? Banka Maruyama came to Taiwan as a tourist to mountaineer and sketch natural sceneries between the third and fourth year after the voting on the Eight Views. He and what he called “landscapes” can serve for us to digress from 1927. The view-voting spectacle of that year and its historical precedents and relevant subsequent events will continue to demonstrate a unique style of Taiwanese tourism. (To be continued)