Browse

Description of space is never a purely natural event. The formation of geographical concepts and narratives has always reflected the culture, politics, and aesthetic agenda of a certain historical moment.(註1)

Through 1927, we can get a glimpse of the “method” for generating the Eight Views of Taiwan; we can also roughly understand the “function” of the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition—the imagination and options regarding beauty and appreciation can no longer result from objective experience once a “theme” is established. When government-elected landscapes meet government-organized art exhibitions—the Eight Views of Taiwan represent the wonders of the “southern country” tailored for/by the Japanese imperial culture. Does this mean that the gaze of the colonizer was transferred onto the painters who were creating cultural landscapes at the time?

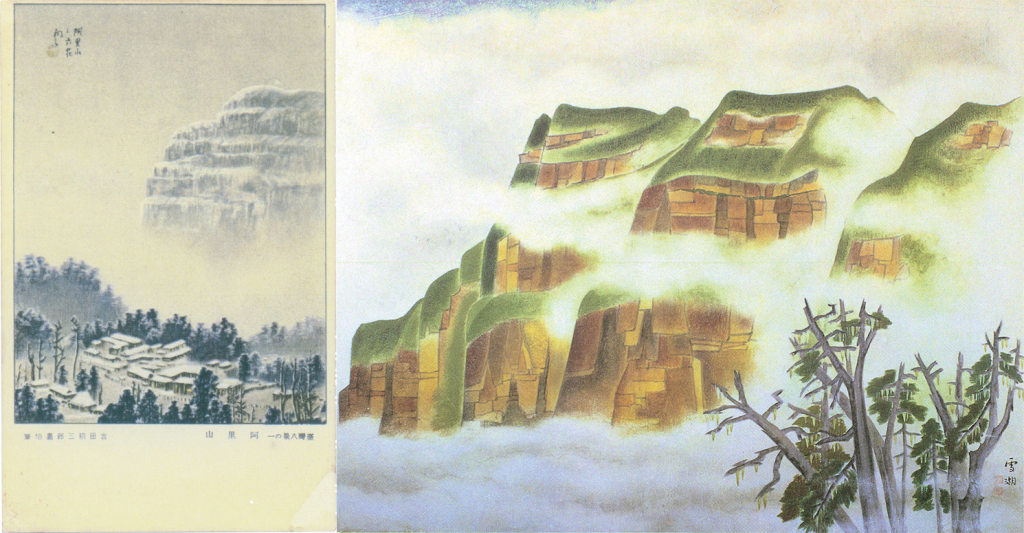

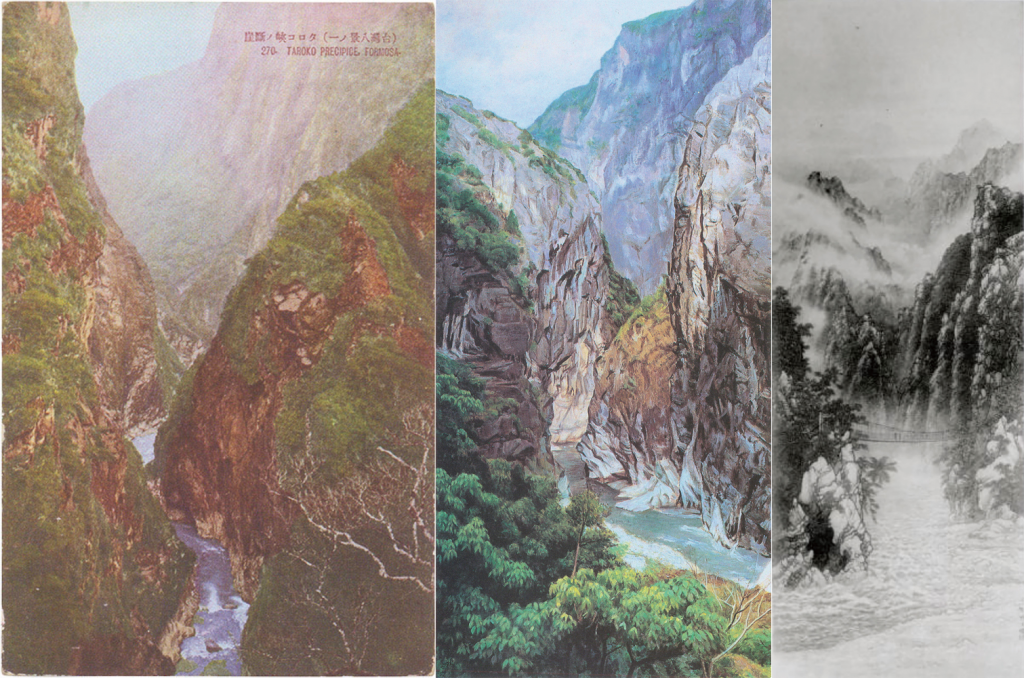

In the first Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition, entries of the Western painting category, including Satora Watanabe’s The Landscape of Tamsui, Itaru Sato’s Tamsui River, and Takeo Kamada’s Santo Domingo Hill were all created based on Tamsui, one of the Eight Views. In the Eastern painting category, Shiken Kato’s The Taroko Gorge and Cluster of Mountains and Layers of Greenery (from Inside Taroko) depicted the mountain views of Taroko, also one of the Eight Views. Kinichiro Ishikawa’s demonstration work Jiaobanshan Path was a sketch of one of the Twelve Wonders. Again and again, traces of the Eight Views, Twelve Wonders and Two Special Sites of Taiwan can be easily found in every subsequent edition of the Taiwan Fine Arts Exhibition. These local sceneries, re-presented through the eyes and brushes of painters, did not directly depict the roads and railways that stood for colonial “achievements” or industrial development. However, through the production of sketched images, they brought forth agreeable views carefully planned by the ruling class and accessible to public visitors. In other words, when painters chose to keep away from the busy city and enter and observe natural sceneries to search for landscapes in Taiwan beyond the industrial and modernized sights, they were extending the scope of landscapes at what Lu Shao-li in Exhibiting Taiwan calls the “front stage” through their artistic practices:

Keeping away from the railways meant a departure from the standard horizon defined by those in power. However, even when these painters left railways and roads, the role they played still represented an extension of power. They were working in the establishment again and, through the power of the establishment, they wanted to convey to travelers who had not embarked on their journeys yet the locations of “virgin soils”. As a result, the new virgin soils would resurface in official travel guides. They tried to deconstruct the uniform landscapes in the “front stage” established by the government and make the scope of scenes in the “front stage” even more extensive. Viewed in this light, the painters were the vanguards in the extension of power. When intending to move beyond the standard horizon defined by those in power, they ironically extended and expanded the reach of such.(註2)

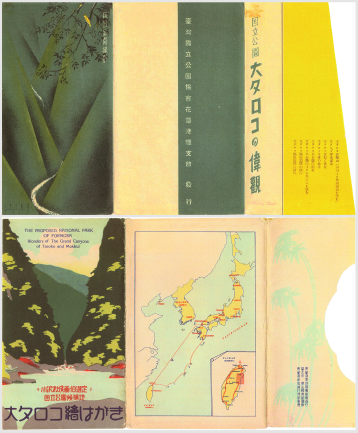

And when the ruling class extended the reach of their power to the new Eight Views of Taiwan, it was not surprising that a series of landscape impressions based on the standard “horizon” gradually surfaced—they were not only repeatedly rehearsed in big art events held yearly, but also reflected the travel routines in Taiwan from the 1930s onwards. Looking back at the images themed on the Eight Views of Taiwan from the Japanese colonial period, we can easily identify many compositional patterns of scenic spots that repeatedly appeared in various media.

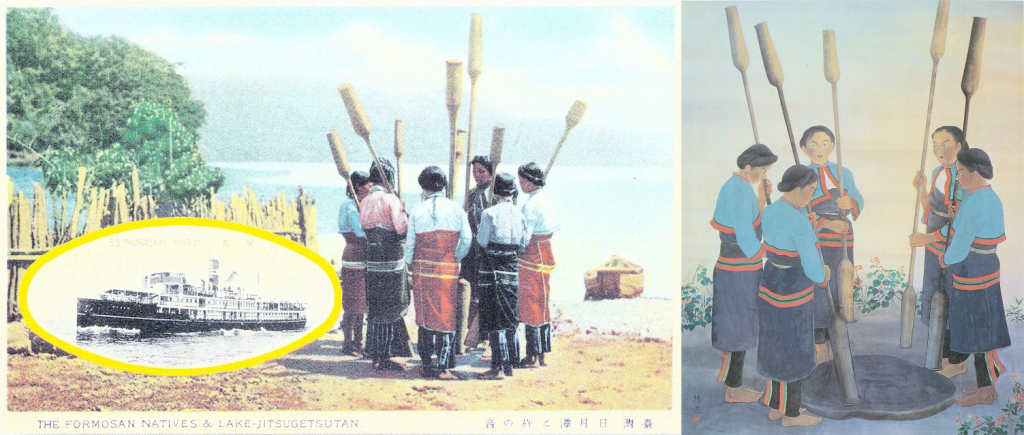

Take Alishan, Sun Moon Lake, and Taroko, which are still popular tourist spots today, for example. We can see the ways in which a certain kind of “best perspective” with which we observe Mount Daito (present-day Datashan or Mount Data), the highest peak of Alishan, was recreated in landscape photography, ehagaki (collection of pictorial postcards), and the paintings of Chen Cheng-po, Kuo Hsueh-hu, Yen Shui-long, and others. We can also find Thao women pounding grains and making “pestle-pounding music/songs” by the Sun Moon Lake, whose body outlines were almost identical in the Nihonga painting of Chen Chin and the tourist advertisements of Osaka Shosen Kaisha (OSK; a shipping line company based in Osaka). We can also discover Taroko Gorge, which angle always looks exactly the same regardless of the techniques used for its framing, shooting, printing, and drawing.

These beautiful “coincidences”, on the one hand, bear witness to Banka Maruyama’s statement: “Landscapes are sceneries. What we praise as a landscape must have something distinctive. Only places with the best sights can be called landscapes.” On the other hand, do they also demonstrate a method for establishing a mainstream culture and experiential identification, with a long history and centered on landscapes?

Perhaps the question we should ask is: When image production implemented by various “units” that purport to appreciate local beauty and landscapes actually presents the same narrative again and again, what does this exactly reflect, the universal or the colonial?

At any rate, such identification with the land that was directed by the colonial government and constructed by landscapes deeply penetrated into the daily experience of Taiwanese society at the time. The song Our Taiwan written by Tsai Pei-huo in 1929 suggests so; traces of Sun Moon Lake and Alishan can be found in the Taiwanese subjective significance that the song expresses.

Artistic Theme

We might say that landscaping activities named after the Eight Views of Taiwan during the Japanese colonial period not only created landscapes but also an artistic theme. However, where did the term “eight views” originate from? A cursory survey of relevant literature will direct our attention to the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang, which originated in the Hunan region of China over 1,500 years ago, and to the extraordinary context of common themes and cultural images in the history of East Asian poetry and painting.

Semantically, descriptions of the “eight views” in poetry can be traced back to the period of the Six Dynasties of China. The poet Shen Yue composed the Odes to the Eight Views, which consists of eight poems in celebration of the eight views. According to relevant literature, the juxtaposition of “eight” and “views” originated from Taoist terms that refer to celestial beings visiting scenic spots while flying in heavenly vehicles. It was also styled the “wonderful views of eight treasures”, “heavenly views of the eight trigrams”, and “scenic views of eight images”. For example, in “Instructions for Shaping Destiny I”, Volume 5 of Declarations of the Perfected, Tao Hung-ching writes: “You said: ‘the celestial beings have a vehicle for visiting the eight views, with which they travel upward to the realm of supreme clarity.'” As for why the views are eight in number, the common theory is that it is associated with the culture of the eight trigrams in Taoism.(註3)

Relevant documents that mention the term “eight views”—derived from the Taoist legend in which the heavenly vehicles of celestial beings descended on Earth—marked a turning point in the history of local landscapes and its poetic and graphic narratives. All indicate that it started with Eight Views of Xiaoxiang, a set of paintings of the landscapes around the “lakes and rivers” region by Song Di, a civilian court official in the Northern Song dynasty. This legendary artwork, which is lost to us, was highly praised by Shen Kuo in his Dream Torrent Essays, and was later collected in the Xuanhe Catalogue of Paintings compiled by Emperor Huizong of the Song dynasty, who was enthusiastic about literati painting. It sprung a hot trend in the international “artistic circle of academies/courts” after the 12th century.(註4) Through exchanges among literati, envoys, painters, Zen monks, and laypeople, this style of landscape poetry and painting that began with Song Di and depicted “picturesque” landscapes of the Xiaoxiang region would then be imitated, copied, reproduced, and spread in Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and other places. In addition, the unique feature of the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang is that they materialize a “conceptual landscape” that combines fiction and reality—although they depict landscapes of the Hunan region in China, the exact location is not specified. Take paintings of the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang in the Southern Song dynasty for example. The expressive method emphasized sights in the south of the Yangtze River, “fixing moist air and nuances of light and shadow on scrolls“, rather than representing the landscape of a single location.(註5) Perhaps it is precisely because of the conceptual nature of the landscape, plus the historical context of landscapes in the south of the Yangtze River depicted by Song Di, a civilian court official from the north of China, that creations themed after the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang opened a possibility for regional diversity. As Massaki Itakura points out in “Eight Views of Xiaoxiang as an Image of East Asia”:

If we approach this phenomenon in a broader context, this theme already had elements of both the north and the south in China’s founding era. But when this theme was being accepted by painters, it was only done selectively due to their personal consciousness and local climates in their places of residence. For Japanese painters, who found the humid climate in the south of the Yangtze River more familiar, the development of ink wash landscape painting was closely connected with the culture of Zen gardens. Korean painters, on the other hand, found freezing weathers more familiar and developed a history of painting centered on people and themed on cold forests.(註6)

Therefore, in response to changes in time, space and geographical context, the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang, which were passed down from different cultural backgrounds and creative mindsets, not only developed a variety of “expression of the eight views” in terms of painting style, but also ramified into various “local eight views” in different geographical environments. As circumstances changed, the culture of “Xiaoxiang”, which represented the geographical location of Han Chinese culture, gradually declined, while the culture of “wonders/holy places” closely related to the “eight views” continued to develop their own sceneries subsequently in the artistic development of East Asia.(註7) There are still many historical changes of the Eight Views that have yet to be explained. However, since this essay focuses on the context of the “Eight Views of Taiwan”, let us turn back to Taiwan.

Aesthetic Experience

The “eight views” culture, which originated in China, was finally transmitted to Taiwan as the Qing empire became the ruler of the island. In response to the circumstances of the time, the eight views in this island consisted not only of the naming and writing of space and geography, but also a “starting point in the search for a homogeneous aesthetic space between the island and the mainland” that reflected a nostalgic longing for the Han Chinese culture centering on the Central Plains.(註8)

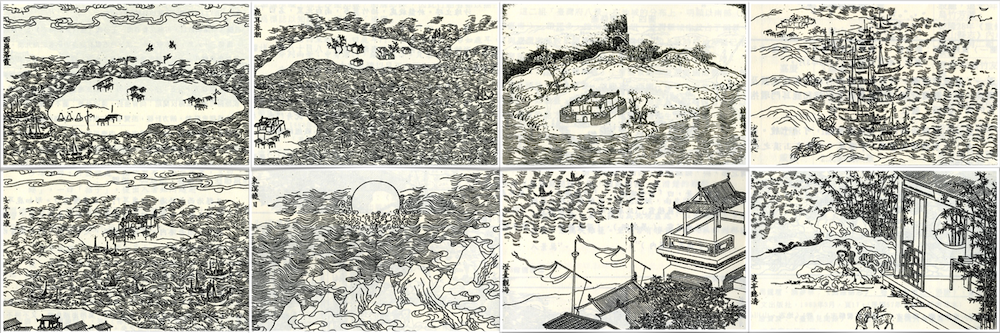

According to existing written records, the first Eight Views of Taiwan appeared in the Gazetteer of Taiwan Prefecture, the first officially published local gazetteer in 1696 (35th year of the Kangxi Emperor’s reign). It was compiled by Kao Kung-chien, Commissioner of the Taiwan-Amoy Circuit, and collects several Poems on the Eight Views of Taiwan by Kao Kung-chien, Chi Ti-wu, Wang Shan-tsung, and others. The first graphical form of the Eight Views of Taiwan appeared in 1747 (12th year of the Qianlong Emperor’s reign) as a print titled “Eight Views of Taiwan County” in the revised edition of the Gazetteer of Taiwan Prefecture edited by Fan Hsian and Liu Shih-chi.

The “night ferries of Anping Harbor”, “fishingboat lights on the sandbar”, “springtides at Lu’er”, “snowfall in Kelung”, “sunrise at the East China Sea”, “sunset at Pescadores Island”, “crashing tides of Fei Pavilion”, and “seaview of Cheng Tower”: these eight views, which sound quite unfamiliar to modern ears, all featured sceneries of coastal areas—in stark contrast to the eight views from the Japanese colonial era that were distributed all around Taiwan and consisted predominantly of mountain views. With an aesthetic agenda based on his nostalgic longing for the homeland and the ingrained geography of the Central Plains, five of the eight views in Kao Kung-chien’s writings were located in Anping, Tainan—the center of the Qing Empire’s rule in Taiwan, while two of them (Fei Pavilion and Cheng Tower) were even located within the quarters of the Taiwan-Amoy Circuit Commissioner’s Office in which he was based. Such writing on landscapes named based on the (personal) experience of the rulers (colonizers) represents the original form of the term “eight views” in Taiwan and reflects the colonizers’ power consciousness that defined Taiwanese landscapes in terms of Han Chinese culture.(註9)

In general, poetry and paintings of the Eight Views of Taiwan under Qing rule were a cultural activity restricted to court officials and local gentry. With imperial expansion over hundreds of years, the “eight views”—the aesthetic imagination that came from the Xiaoxiang region in China to Taiwan—re-appeared in artistic themes that purported to embody local diversity but were in reality only established within the specific communities of Han Chinese government officials and literati. In other words, the power to name and interpret landscapes neither belonged to, nor was associated with, local people. Looking back at the 1927 Eight Views of Taiwan, which were planned and engendered by the Japanese government and endorsed by “public opinion”, we might say that landscapes of Taiwan during the Japanese colonial period were finally brought out of specific social circles. However, did the political geography originated in a different “other” actually lead to more uniform sceneries?