Browse

They cannot make history who forget history.

–Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar.

Art is considered as a universal language, but are there differences in art? Who are the people with differences in their art practices? Why do they think that a particular discourse should be put into practice? In South Asia, the majority of people are still excluded from the concepts of beauty of those who exclude them. Thereby, denying their existence. According to Brahmanism, we are excluded. We are not beautiful, our colour, appearance, songs, instruments, food, names, labour, education or wealth is not worthy. Our sisters and daughters are not beautiful, we have nothing beautiful, not even our life. Moreover, if any of this is at all considered beautiful, it will be forbidden. The role of such hatred is in the existing heterogeneous system.

Hence, how do we accept the concepts of beauty from those who try to enslave us? Therefore, the differences in the concept of ‘beauty’ are practiced. We reject the culture of beauty in heterogeneity. We embrace the philosophy of emancipation based on the idea of beauty with beautiful humane thought. The issue of which side our art and culture stands is important to us. What could be more beautiful than to practice the discourse that denies the system of exploitation, which has been going on for thousands of years? Our definition of beauty will be one that is born out of the value of life.

Art never exists alone, it comes with certain ideas, sometimes a creation is made by consciously keeping certain thoughts in mind, sometimes it is indirect consciousness of the mind and without any pre-decided thought. We learn from history. Especially, for those whose history is not to be forgotten, history always stands as a lesson and a doctrine. Exploitation imposed by the man-made system on the exploited and their liberation from it by human beings, both aspects are important in the journey of mankind.

If one thinks that the exploited are liberated from this exploitation and inequality, it is not so. This process of liberation continues uninterrupted over time and progressive people have to keep this struggle alive by consistently participating in the process. To express the suffering of the section of society from which we come and thereby become part of the system that seeks to alleviate that suffering, is one aspect, while to express the hostile role of human exploitation and endorse such a culture is the second aspect.

While dealing with this we should discuss revolution and counter-revolution, and ask why there is a revolution and a counter-revolution? Truth never lies. It is a necessity and urgency of our time of emerging fascism, extremism, rising caste violence, normalisation of communalisation and violence, lynching and social injustice. Subalterns can speak but, are they being heard? It is important to speak about Ambedkarite aesthetics and politics; it can be a reflection of the suppression of dissent, whether it is in politics or art. It is concerned with lived experiences of oppressed communities, which are often excluded from the mainstream art world and de-focussed from curatorial practice.

Buddha ushered in a great revolution in ancient India, about which Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar said, “Buddhism was as great a revolution as the French revolution”. There have been revolutions and counter-revolutions elsewhere in the world, too, the prominent ones being the French and the Russian revolutions. There too, revolutions were followed by counter-revolutions, where art and literature played vital roles. However, some litterateurs and artists distance themselves from such revolutions and counter revolutions, thereby severing any political, social and economic links with the contemporary world around them. They take a neutral stand by saying that art is for art’s sake and an artist has nothing to do and should have nothing to do with the exploitation, slavery and misery around him. An artist’s self-portrait exists in his environment and attitude towards life, which mirrors his inner politics.

Simply by being alive, you make a difference. You are part of the problem and can also be part of the solution; therefore, I strongly state, I can interpret social politics through visual expression as ‘Aesthetics of Liberation, Aesthetics of Revolt and Aesthetics of Assertion’. Through our curatorial vision, we encourage expressions as forms of assertion and of social consciousness, which reflect human conditionings and social realities.

Justice Mahadeo Govind Ranade, a social reformer, scholar and Marathi author, took the initiative of organising the first Marathi literary conclave in 1878. It was held under the banner of Marathi Granthkar Sabha. He invited Mahatma Jyotirao Phule, a social revolutionary, for the meet. Mahatma Phule not only rejected the invitation, but also condemned the organisers for taking a soft line on the issue of caste exploitation and accused them of perpetuating Brahmin hegemony. The issue is, to clarify yourself and deny their protected ignorance and not let others put you in a frame you don’t want to be in. It is important to build your equity. No outsider (because if both sides are inclusive, then the level of acceptance is much greater) can lift you as a messiah. The market and trends will come and go, but the only thing that can remain in existence is your work and the politics around it.

This is an attempt to examine three contemporary artists and an art movement attempting to blur the boundaries between being an artist and a cultural activist. I focus on three artists namely, Savi Savarkar, Ranjeeta Kumari and Vikrant Bhise and the Secular Art Movement, Maharashtra, India. The challenges confronting these artists become an assertion of their voices. For them, art practice is a tool to cultivate a discourse. Since art and politics cannot be separated, they have found the root of their art practice in cultural politics.

Secular art Movement: Hear the voice of the voiceless!

It is an artists’ movement founded in 2018 and run by artists. A movement based on the Phule-Ambedkarite aesthetics and philosophy, the idea of freedom, democracy and anti-caste movement, which believes in the idea of creating a secular society as enshrined in the Indian Constitution. Through various activities and art interventions, they repudiate caste discrimination, fascism and the manmade system that is responsible for human slavery, suffering and exploitation. They endorse secularism, social justice, equality, and freedom.

According to their stance,

Secularism is an element that can liberate human beings from slavery, grief and exploitation by intervening in religious systems of all faiths, as well as other systems influenced by it, which are responsible for human slavery, grief and exploitation.

In the Indian art world, caste reality, injustice and atrocities against Dalits are still not openly spoken. As an exception, even if someone speaks, he or she will probably neither refute the system at the root of the problem nor take a stance against it. The Secular Movement has been started with the purpose of holding the man-made system accountable for human exploitation, through ethical intervention within the framework of the Indian Constitution.

To serve this purpose, activities such as a large workshop of 50 like-minded artists at the footsteps of the world heritage Ajanta caves was organised in 2019, to celebrate the 2nd centenary year of the discovery of the caves. This workshop was based on the book, Revolution and Counter Revolution, written by Dr. Ambedkar. The intention behind it was to bridge the gap between art, artist, society and ideologies. Hence, the artists engaged with the masses through various art activities, like artistic activism to protest against anti-constitutional laws, normalisation of communal violence and injustice.

It is important to speak about the movement, because it clearly stands out, talking about the Ambedkarite discourse, which has not been celebrated so far. It is very important to bring this idea to the Indian art world after witnessing and experiencing bitter socio-political ethos existing in the country.

The defiance of the mainstream discourse made them bring this narrative, which is the common thread among their practices, in focus. They do not defy the mainstream only to glorify victimhood, but also disclose and refute the reasons behind it. It is their intention to build a platform that brings together all the Dalit-Ambedkarite artists and to work as an institutional alternative with inclusive practices as a movement.

Savi Savarkar: Unfolding the Revolution and Counter-Revolution

Savi Savarkar is a Delhi based artist, Born in 1962. Savarkar is one of India’s most important artists representing the critique of the caste system. His art is most significant for expression of his social experiences in South Asian culture as a critique of the caste system in India. Dalits and untouchables, with over a billion people in the country, are still exploited and oppressed because of their lower strata in the caste hierarchy. Savi Savarkar raises questions about the causes of that exploitation through his critical work and makes statements on the system responsible for the exploitation.

The history of social reforms in India begins with the Buddha. In fact, the history of any social reform is incomplete without the history of Buddha. Buddha is not as calm and spiritual as he has been portrayed, but a rebel. Feeling the sorrows of the world, the Buddha seeks the reasons for their suffering. Yet he has been portrayed with his eyes closed. Isn’t this immoral?

Savi Savarkar’s art has a unique content which is directly associated with his own experiences about caste discrimination, social exclusion and ostracism. The social exclusion gives him social responsibility. So that he should do it through his work of art. He can question and reveal through his art. One of the series is called ‘Untouchability during the Peshwa rule in Pune’. The situation, then, was very bad. The plight of Untouchables’ was very bad. They had to walk the street, as per the norms prescribed in Manusmriti, which talks about the earthen pot around their neck and the broom on the back. The earthen pot was to prevent him from spitting on the ground as the earth would have become polluted. So, he had to spit inside the pot. The broom on his back was to erase his footprints. The stick with tingling Ghungroos (small metal balls) was to warn people that an untouchable was coming their way. Even his shadow was not supposed to fall on the upper castes.

He says in one of his informal conversations, “When I entered the fine arts college, the whole aesthetics were Brahminical, and there were no aesthetics for us. Then I thought that I have my own cultural background, my own journey, my own direct experiences, which is my perception as a big resource to pave way towards my aesthetic journey. My art has the foundation of Buddhist aesthetics. I can say now it’s the Ambedkarite aesthetics and my art’s conscience is non-violent struggle, because we are Buddhists.”

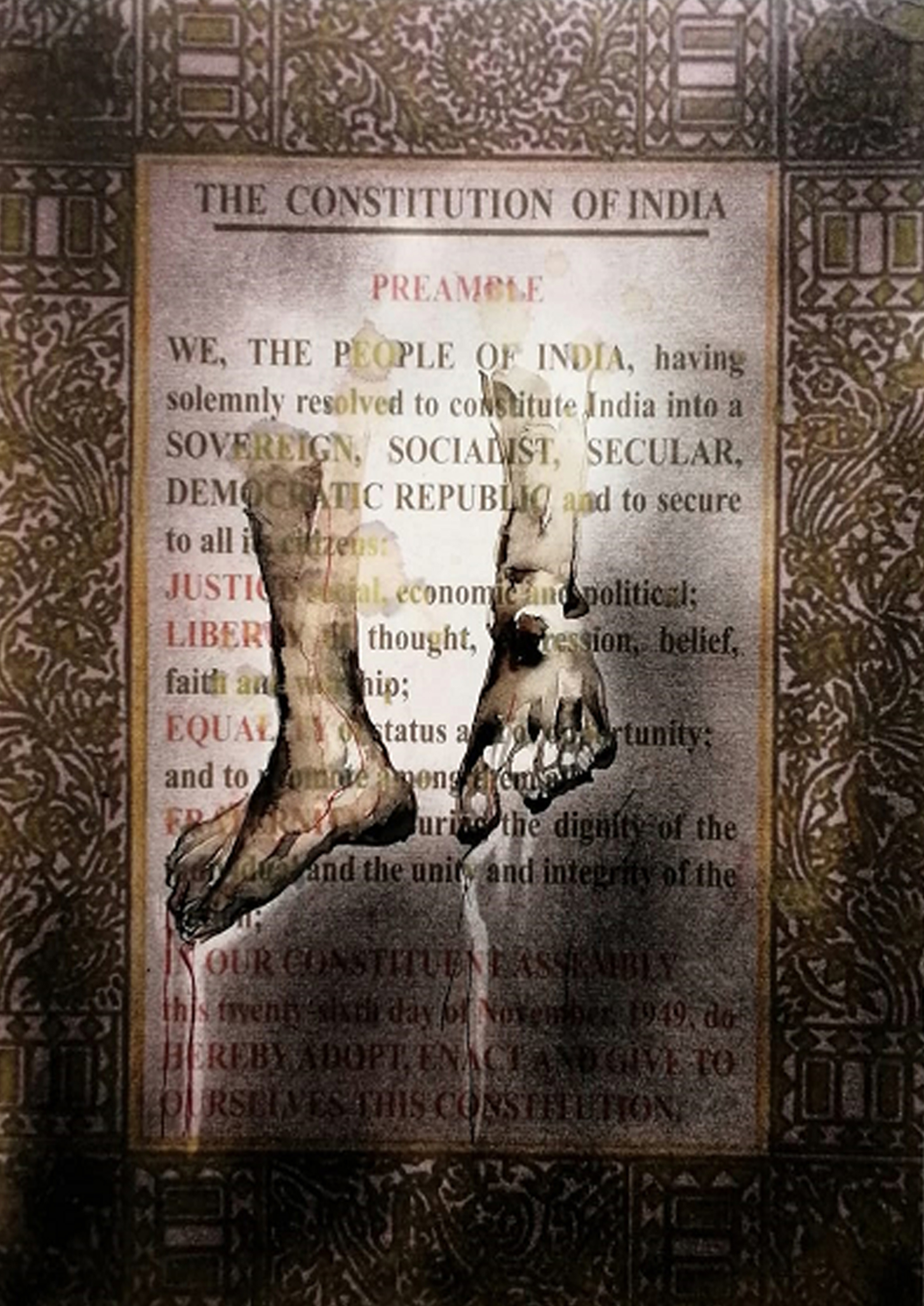

Ranjeeta Kumari: The Constitution: Beauty of values and dignity

Art of the age has to reflect the spirit of the age.

—Richard Bartholomew

Ranjeeta Kumari, who was born and brought up in Bihar, is a conceptual artist who studied at the Shiv Nadar University outside Delhi. Ranjeeta predominantly engages with the ‘aesthetics of labour’ to create a ‘visual Identity of the marginalized’. ‘Displacement’ and ‘migration’ have been constant threads throughout her works, as she registers the unacknowledged workers and their contribution towards the city. She examines the cultural values and aesthetics of labour associated with found objects through language, race or caste in India. Her endeavor is to understand and research on the life of workers (the marginalized) under capitalism.

The Constitution of India which became effective from 26 January 1950, laid down the framework demarcating fundamental political code, which ensures fundamental rights for its citizens in equal measures, declaring India as a sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic; assuring its citizens justice, equality, liberty, and fraternity. Ranjeeta concerns the landless labourers or farmers as they adapt to the pressures of the shifting times, depleting resources they inherited if any; entrapping themselves within the matrix of the city, once again as labourers of the concrete world.

“I have chosen this object to express my interpretation, in particular, of the situation of unacknowledged workers and their contribution to building the city. I got this object (Vinda) they use for carrying heavy loads, from a labour site. I started collecting old items (Vinda) like the cloth and sacks, from the labourers in exchange for new items and presented them as an installation, imagining a city made up of these objects. I collected items from the workers for three straight months. This process had an added benefit as the new things the workers received got them excited and they indulged in a lot of animated talks about themselves- their lives, their culture, likes and dislikes and a lot more. So there is an audio interview with workers. The conversations also created a unique relation between me and the workers, and this was heartening especially because these people belong to my own state, Bihar. I realized that though my state has a rich history, its current status is that of a poverty-stricken state and that is one reason why people are moving elsewhere in search of better livelihoods.” said Ranjeeta.

Vikrant Bhise: ‘Ambedkar’ as an icon of emancipation.

Men are mortal. So are ideas. An idea needs propagation as much as a plant needs watering. Otherwise, both will wither and die.

– Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar.

Vikrant Bhise, a conceptual artist based in Mumbai, completed his GD. Art diploma in drawing and painting in 2010, L. S. Raheja School of Art, Mumbai and D. P. EAD. 2011, Sir J.J. School of Art, Mumbai.

A worker cleaning a statue of Dr. Ambedkar. In today’s time while changes in labour laws in India are being implemented in Covid times, apparently to stabilise the economy and recover the impending losses, we remember Dr. Ambedkar and his contribution towards the labour movement and labour welfare, during this national crisis. His contribution and labour laws which he incorporated as protective measures of a developing country and its people, especially the vulnerable ones. ‘Dr. Ambedkar symbolises the Constitution and the notion of equality, which becomes the fundamental reason to invoke him in current times.’

He documents his recent observations of the migrant crisis as spontaneous solidarity of human conditions. He marks the 21st century, a century of science and technology, which has achieved astronomical proportions and quantum speed, where we are supposed to be better prepared to face such a crisis, but in reality, lack direction and better leadership. A microscopic virus, Covid-19, leaves the superpowers in tatters. India declares a national lockdown. The virus pervades the entire society gradually, transmitting from the upper to lower classes, snatching away livelihoods and the daily bread of the migrants.

A realisation of having no home in the city and no choice but to return to their homes in villages far away. There is fear of certain death- not due to Coronavirus, but due to hunger. Compelled to journey on foot, braving the sun and rain, with families, belongings and children on their back, as major transportation services shut down. While some of them hide inside milk containers, some are riding in overcrowded rickshaws to cross the state borders.

Working with socio-political motives is nothing new in the Indian art world. Local socio-political issues as well as national and international issues have been dealt with. But, unfortunately, Indian art world is ignorant of caste in its expression and has never expressed much about the inhuman inequality and violence arising out of caste-based oppression and religious frenzy, as the core problem of the nation.

It is a pity that as an individual, a society, a country and a nation, we do not realize that we lack solidarity because of our own mistakes. The genocide and violence all around us make me feel like I’m being wounded. These deaths are not individual, they transform into a collective plight. The Phule – Ambedkarite movement, by making every person and his community free from suffering, slavery and exploitation, seeks to restructure society on the principles of freedom, equality, brotherhood, justice and secularism. In short, the goal of emancipation is the Ambedkarite aesthetics.

We insist on treating art and culture from the perspective of human liberation from a pragmatic and secularist stance. Literature and art are key components of culture and therefore, Ambedkarite aesthetics consider it necessary to reject the culture which devalues human beings through its art, literature and traditions. There is a straightforward formula of Ambedkarite aesthetics. India’s fundamental social problem is its caste system, which is considered to be divinely ordained in the holy texts.

Even though it has other material considerations, the religious system/ philosophy has created a mentality of people in favour of the caste system. Even after experiencing its deadly and disgusting nature, the Dharmashastra still does not tolerate any voice or action against the caste system. This system even does not hesitate to kill people, therefore, ethical intervention in the system of religion in the process of caste annihilation is inevitable and the dominant element that intervenes in such religious systems is the Ambedkarite ideology.

Bibliography:

Prabhakar Kamble is an artist, curator and a cultural activist, he lives and works in Mumbai. He has completed his post Diploma in Art education and GD art Diploma in drawing and painting from Sir J.J. school of Art Mumbai and L.S.Raheja School of art Mumbai respectively. His practice involves curatorial projects in equal measure as does his personal practice. His practice is informed by kinetic installations, performances, drawings and Paintings. He responds and represents his immediate social realities as well as personal and collective histories. His performances are often complex commentaries on the society, marked by symbolic use of material, either found or made.

Within curation he delves into social realities as an expanded political subject. He recently curated a large format residency-workshop, where he assembled fifty artists at the world heritage site of Ajanta Caves, a huge online group show, Broken Foot-Unfolding Inequalities, collaborated with Mojarto.com and NDTV India. His other curations include Working Practices, at The Showroom, London, Outsider at Zero Eight 21, Mysore. Solo show includes Existential (Clark house Initiative Mumbai, 2017) and Agitation of Restless Mind (Jehangir art Gallery, Mumbai, 2016).