Browse

One thing most people who work with sound readily agree about is: there is no singular listening. On the most basic level, listening is often contrasted with hearing – the latter being the physical sensing of pressure waves, and the former being an intentional and attentional practice of acoustic perception. From philosophy to composition, and from sound studies to sound art, listening has been differentiated, pluralized and multiplied according to different methods and metaphors.

For Theodor Adorno, listening was a matter of style, with each type of listener representing a sociological reaction to music; for Pierre Schaeffer, listening was possible in four different modes, each affording a different relationship to sound; more recently, Henry Torgue has outlined three aspects of listening, while Eric Clarke has revisited the ecological theory of perception and argued that it is possible to practice listening in innumerable ways.

Each of these conceptualizations of auditory perception – types, modes, ways, aspects of listening – is not simply a refinement of analytical categories: it creates shared worlds, it shapes sounding practices, and it reinforces models of sensory perception. Even just talking about listening as a definite domain of practice implies a model distinguishing between five distinct human senses. Different models of listening lead to sharply distinct, at times even conflicting concerns.

The “auditory turn” championed by Don Ihde relies on a phenomenological inquiry that follows and expands on Schaeffer’s reduced listening, mobilizing Husserl and Heidegger to think through the horizon of one’s own auditory experience. Ecological models of listening, building on James Gibson’s ecology of perception, emphasize the influence of events, experiences and environments on audition[1], promoting the practice of deep listening as a way of attuning oneself with the world.

Historical models trace ways of listening back to their social construction and material shaping, dismantling ontological preconceptions about audition and connecting technological development with cultural changes. Pushing this effort one step forward, epistemological models rely on ethnographic collaborations to understand how listening itself – and sensory experience more broadly – is articulated as a way of knowing in situated contexts. While most models of listening remain anchored to the human ear, a growing attention to vegetable, animal, planetary, machinic and alien audition outlines the contours of non-human models of listening to come.

Multiple models of listening emerge and intersect throughout the writings collected in this special issue. Itaru Ouwan’s “Electric Phantom” connects the phenomenological scaffolding of musique concrète with the non-human materialist energies of high-voltage current, and Tenn Bun-ki’s exhibition reviews foreground the technological relationships and operational traces hiding behind phonographic listening. The essays by Au Sow Yee and of another external link (Ho I-Lin) conjoin historical research into radiophonic listening and broadcasting with concerns for sonic memory, while reports by Yan Jun and Gabriele de Seta offer situated vignettes of listening events and sounding practices in Singapore and Taipei.

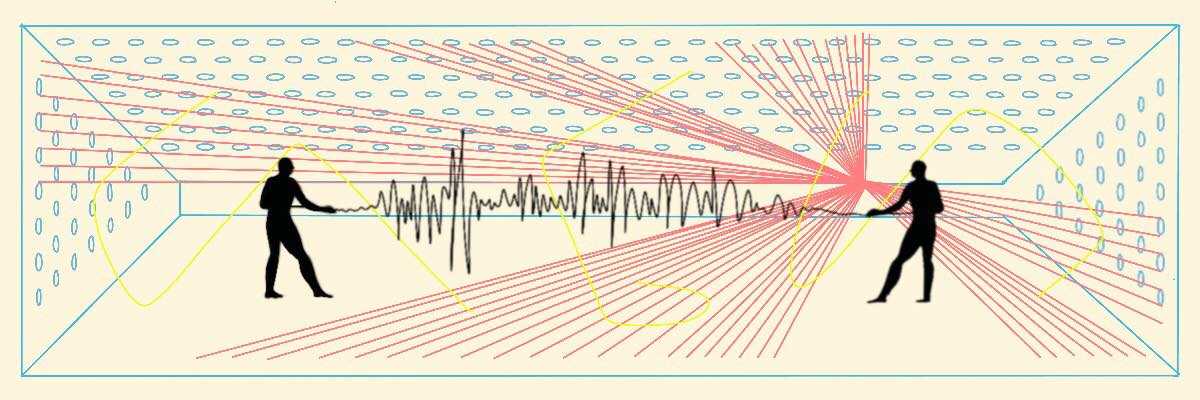

Ultimately, while few would disagree about the multiplicity of listening, the types, modes, aspects and ways of auditory perception remain categorizations that are phenomenologically opaque, historically determined, and epistemologically situated. As Anja Kanngieser notes in her answers to “Four Questions on Field Recording”, listening is a central component of her creative practice, and it comprises “things that apprehend my body beyond my ears, frequencies that vibrate on my skin, inside my organs”. New, experimental and mongrel models of listening are necessary to account for this expanding vibrational world.

[1] Gaver, W. W. (1993). “What in the world do we hear? An ecological approach to auditory event perception”. Ecological Psychology, 5(1), 1–29.