Browse

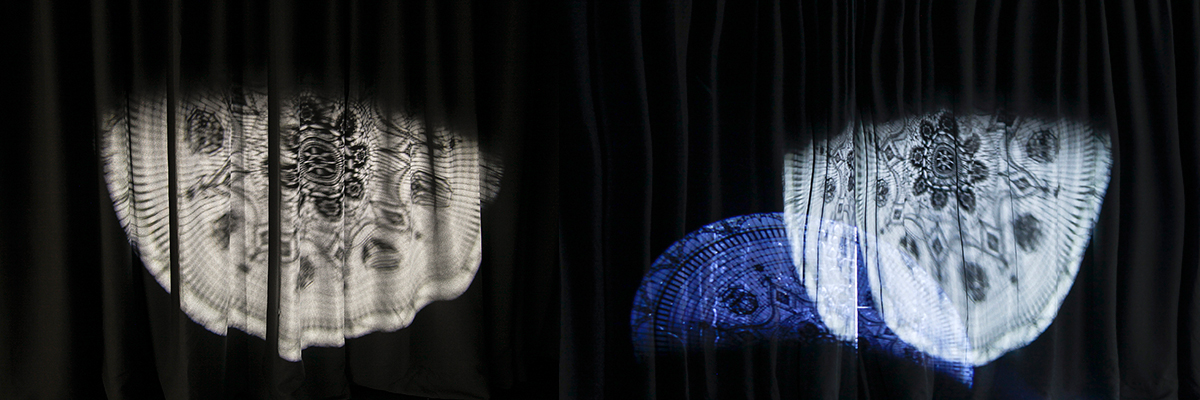

(Cover: Jaeyeon Chung, “A Sketch for a Foundation”, We Are Bound to Meet: Chapter 1; Many wounded walk out of the monitor, they turn a blind eye and brush past me. 2019)

We find the Cold War’s enduring reflection in present-day discriminatory patterns, especially against ethnic Chinese region-wide, but also, for instance, against the branded-recalcitrant Thai northeast. Nor have we found abundant willingness to consider or redress past violence, a reality most evident and problematic in Indonesia, site of breathtakingly brutal and sweeping anticommunist mass-murders in the mid-1960s, and in Vietnam, where still today the politics of unification after 1975 remains unaddressed. In this post-traumatic landscape visions of the nation-state remain challengingly polarized, marked by binary thinking about “us,” “them,” and the limits of political and ideational community.

—Eva Hansson & Meredith L. Weiss, “Editors’ Introduction: Beyond the Cold War in Southeast Asia”, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia – Issue 26

In “Editors’ Introduction: Beyond the Cold War in Southeast Asia” of the latest Issue 26 of Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, the editors have listed the traumatic memories and the “post-traumatic landscapes” of Southeast Asian nations, among which Indonesia had suffered from the most severe ethnic conflicts in 20th century. They mentioned that the society is polarized by the binary vision of “us” and “them” until now, and is incapable of facing its trauma, no matter such vision is based on religional, ethnical, or other cultural factors. Nonetheless, our correspondent Zikri Rahman had interviewed the renowned historian Thongchai Winichakul, the author of Siam Mapped, during the International Conference of Cultural Studies Association in March, 2019. Professor Thongchai Winichakul was also suffered from the October 6th Massacre in 1976, and had witnessed the terrifying history of purging the country of communist anti-monarchy force. Although “many people disillusioned (with the ideology of communism),” the society is still lack of the courage to face its killing history.

The truth is, the complexity and conflict inside each Southeast Asian country not only have stemmed from the division during the Cold War period, but also could be traced back to the early nation building stage, when the ideologies of colonialism/ anti-colonialism, imperialism/ anti-imperialism, and national self-determinism coexisted and confronted with each other. It’s hard to blame it on one enemy. For instance the Japanese militarists justified the invasion in the name of Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere by claiming the abolishment of colonialism and supporting Indonesian independence. On August 17th, 1945, under pressure from radical and politicized PETA (Pembela Tanah Air) Sukarno and Hatta proclaimed Indonesian independence on 17 August 1945, two days after the Japanese Emperor’s surrender in the Pacific. As the Dutch, backed by the Allied, tried to re-establish their rule, and a bitter armed struggle lasted for another 4 years to 1949, the Japanese handed weapons to Japanese-trained Indonesians, and almost 3,000 Japanese soldiers joined the Indonesians to fight for their independence – about 1,000 died for the new country. These Japanese were regarded as national heroes, even including some of the Formosan soldiers who felt reluctant to return to Taiwan under the R.O.C. regime after Japanese rule. Neither can the victorious country deny nor can the defeated country admit the complex national identity in such situation.

In this issue, we exam along the faultlines of collective memories from the 228 incident, to the White Terror, to “United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2758”event, to the lifting of martial law. In 1976, Taiwanese writer Chen Qianwu published “Hunting Captive Women (also meaning “woman-capturing criminal” in Chinese)” and received Wu Sanlian Literature Award. The story recounts Chen’s wartime experiences in WWII’s Pacific theater. In the sroty, Lin Yiping, the protagonist then dispatched to Timor, was charged with transporting the captured Indonesian females (the “comfort women”). Lin dubs himself a “woman-capturing criminal.” Based on the post-war discursive practice of the writer’s memoir on the Timur island, we would like to reconsider Chen Hsian-Wen’s Letter.Callus.Post-War (Jul,12 ~ Sept, 22) taking places in both Jogja and Taipei, with the sex slavery as one motif that connects discontinuous Taiwanese and Indonesian histories. It is the forgotten subject under the national aesthetics recognized by the ASEAN artists in the exhibition SUNSHOWER. Also, we could only expose to the comparison of “postwar-ness” in different East Asian countries after Chen had initiated his East Asian poet network and associated conferences into 1980s. (Note: “A Sketch for a Foundation”, created by Korean artist Jaeyeon Chung, is photographed in the Government-General Building of Chosen which used to host the chief administrator of the Japanese colonial government in Chosen from 1910 to 1945. The work is also a part of Tsai Jia-Zhen’s exhibition We Are Bound to Meet: Chapter 1; Many wounded walk out of the monitor, they turn a blind eye and brush past me. in Seoul’s LOOP art space in 2019.)